Mirunga południowa

| Mirounga leonina[1] | |||||

| (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||

samiec | |||||

samica | |||||

| Systematyka | |||||

| Domena | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Królestwo | |||||

| Typ | |||||

| Podtyp | |||||

| Gromada | |||||

| Podgromada | |||||

| Infragromada | |||||

| Rząd | |||||

| Parvordo | |||||

| Rodzina | |||||

| Rodzaj | |||||

| Gatunek |

mirunga południowa | ||||

| |||||

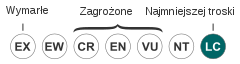

| Kategoria zagrożenia (CKGZ)[25] | |||||

| |||||

| Zasięg występowania | |||||

| |||||

Mirunga południowa[26], słoń morski południowy (Mirounga leonina) – gatunek drapieżnego ssaka z rodziny fokowatych (Phocidae).

Taksonomia

[edytuj | edytuj kod]Gatunek po raz pierwszy zgodnie z zasadami nazewnictwa binominalnego opisał w 1758 roku szwedzki zoolog Karol Linneusz nadając mu nazwę Phoca Leonina[2]. Holotyp pochodził z wyspy Robinson Crusoe, z archipelagu Juan Fernández, w Chile[27].

Autorzy Illustrated Checklist of the Mammals of the World uznają ten gatunek za monotypowy[28].

Etymologia

[edytuj | edytuj kod]- Mirounga: rodzima, australijska nazwa miouroung dla mirungi południowej[29].

- leonina: łac. leoninus „jak lew”, od leo, leonis „lew”, od gr. λεων leōn, λεοντος leontos „lew”[30].

Zasięg występowania

[edytuj | edytuj kod]Mirunga południowa występuje w Oceanie Południowym; miejsca rozrodcze rozrzucone są na wyspach subantarktycznych, Półwyspie Antarktycznym i wybrzeżach południowej Argentyny (Macquarie, Wyspy Kerguelena, Georgia Południowa i Półwysep Valdés)[28][27]. Wędrujące populacje odnotowano także w Australii, Brazylii, Chile, Mauritiusie, Mozambiku, Namibii, Nowej Zelandii, Omanie i Urugwaju[27].

Morfologia

[edytuj | edytuj kod]Długość ciała samic około 300–350 cm, samców 450–500 cm; masa ciała samic około 600–800 kg, samców 1500–3500 kg[31]. Noworodki osiągają długość około 125 cm i ciężar około 45 kg[31]. Wzór zębowy dorosłych osobników: I C P M = 30; wzór zębowy młodych z zębami mlecznymi: I C P = 22[32].

Ekologia

[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Mirungi żywią się głównie głowonogami (75%) i rybami (25%). Gatunek ten żeruje u wybrzeży Antarktydy, zaś rozmnaża się na wyspach wokół kontynentu. Zwierzęta te są zdolne do odbywania bardzo dalekich podróży, pewien młody samiec z południowo-wschodniego Pacyfiku w ciągu 11 miesięcy przepłynął dystans ok. 29 tysięcy kilometrów, oddalając się nawet 640 km na zachód od wybrzeży Ameryki Południowej[33].

Mirungi spędzają większość czasu w wodzie, nurkują typowo na 20–30 minut, na głębokość od 300 do 500 metrów. Rekordowe nurkowanie pewnej samicy trwało 2 godziny[25]; inne zwierzę zanurkowało na głębokość ponad 2000 m[34].

W czasie sezonu rozrodczego samce stają się bardzo agresywne. Walczą wtedy między sobą o terytoria i dostęp do samic. Pojedynczy samiec może panować nad „haremem” liczącym do 50 samic; w przypadku większych grup samic, już kilka samców może z nimi kopulować[35].

Na mirungi polowano w XIX w. dla ich cennego tłuszczu, na Georgii Południowej aż do 1964 roku. Program ochrony tych ssaków sprawił, że ich liczebność podniosła się, osiągając obecnie ok. 700 000 osobników, a ich istnienie nie jest już zagrożone.

Zobacz też

[edytuj | edytuj kod]Uwagi

[edytuj | edytuj kod]Przypisy

[edytuj | edytuj kod]- ↑ Mirounga leonina, [w:] Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ang.).

- ↑ a b C. Linnaeus: Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Wyd. 10. T. 1. Holmiae: Impensis Direct. Laurentii Salvii, 1758, s. 37. (łac.).

- ↑ F. Tiedemann: Zoologie: zu seinen Vorlesungen entworfen. Allgemeine Zoologie, Mensch und Säugthiere. Landshut: In der Weberichen Buchhandlung, 1804, s. 552. (niem.).

- ↑ J.I. Molina: Saggio sulla storia naturale del Chili. Bolonia: Nella Stamperia de S. Tommaso d’ Aquino, 1782, s. 280. (wł.).

- ↑ F.A. Péron: Histoire de l’éléphant marin, ou phoque à trompe (Phoca proboscidae N.): pêches des Anglois aux Terres Australes. W: F.A. Péron & C.A. Lesueur: Voyage de découvertes aux terres australes: exécuté par ordre de Sa Majesté l’empereur et roi, sur les corvettes le Géographe, le Naturaliste, et la goëlette le Casuarina, pendent les années 1800, 1801, 1802, 1803 et 1804. Cz. 2. Paryż: De l'Imprimerie impériale, 1816, s. 34. (fr.).

- ↑ F.A. Péron: Des Avantages que les Anglois retirent des Phoques des mers Australes. W: F.A. Péron & C.A. Lesueur: Voyage de découvertes aux terres australes: exécuté par ordre de Sa Majesté l’empereur et roi, sur les corvettes le Géographe, le Naturaliste, et la goëlette le Casuarina, pendent les années 1800, 1801, 1802, 1803 et 1804. Cz. 2. Paryż: De l'Imprimerie impériale, 1816, s. 66. (fr.).

- ↑ A.G. Desmarest: Phoque. Phoca. W: C.S. Sonnini (red.): Nouveau dictionnaire d’histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l’agriculture, à l’économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine, etc. Wyd. Nouv. éd. presqu’ entièrement refondue et considérablement angmentée. T. 25. Paris: Chez Deterville, 1817, s. 559. (fr.).

- ↑ A.G. Desmarest: Mammalogie, ou, Description des espèces de mammifères. Cz. 1. Paris: Chez Mme. Veuve Agasse, imprimeur-libraire, 1820, s. 239, seria: Encyclopédie méthodique. (fr.).

- ↑ de Blainville 1820 ↓, s. 299.

- ↑ de Blainville 1820 ↓, s. 300.

- ↑ F. Cuvier: Phoque. (Mamm.). W: Dictionnaire des sciences naturelles, dans lequel on traite méthodiquement des différens êtres de la nature, considérés soit en eux-mêmes, d’après l’état actuel de nos connoissances, soit relativement à l’utilité qu’en peuvent retirer la médecine, l’agriculture, le commerce et les artes. Suivi d’une biographie des plus célèbres naturalistes. T. 39. Strasbourg & Paris: F. G. Levrault & Le Normant, 1826, s. 552. (fr.).

- ↑ R.-P. Lesson: Manuel de mammalogie, ou histoire naturelle des mammiferes. Paris: J. B. Bailliere, 1827, s. 202. (ang.).

- ↑ a b c J.E. Gray: Synopsis of the species of the class Mammalia. W: E. Griffith (red.): Animal Kingdom arranged in conformity with its organization, by the Baron Cuvier, member of the Institute of France, &c. &c. &c. with additional descriptions of all the species hitherto named, and of many not before noticed. Cz. 5. London: G.B. Whittaker, 1827, s. 180. (ang.).

- ↑ J.B. Fischer: Synopsis Mammalium. Stuttgardtiae: J. G. Cottae, 1830, s. 235. (łac.).

- ↑ S. Nilsson. Utkast till en systematisk indelning af Phocacéerna. „Kongliga Svenska vetenskapsakademiens handlingar”. För år 1837, s. 240, 1838. (szw.).

- ↑ P. Boitard: Le Jardin des plantes: description et murs des mammifères de la Ménagerie et du Muséum d’histoire naturelle. Paris: J.J. Dubochet et Ce, Éditeurs, 1842, s. 277. (fr.).

- ↑ J.E. Gray: Mammalia. I.—The seals of the southern Hemisphere. W: J. Richardson & J.E. Gray: The zoology of the voyage of the H.M.S. Erebus & Terror, under the command of Captain Sir James Clark Ross, during the years 1839 to 1843. By authority of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty. Cz. 1: Mammalia, Birds. London: E. W. Janson, 1844–1875, s. 4. (ang.).

- ↑ a b W.C.H. Peters. Über eine neue Art von Seebären, Arctophoca gazella, von den Kerguelen-Inseln. „Monatsberichte der Königlichen Preussische Akademie des Wissenschaften zu Berlin”. Aus dem Jahre 1875, s. 394 (przypis), 1876. (niem.).

- ↑ A.E. Brehm: Brehms thierleben, allgemeine kunde des thierreichs. Cz. 3: Hufthiere, Seesäugethiere. Leipzig: Verlag des Bibliographischen instituts, 1877, s. 638. (niem.).

- ↑ J.A. Allen: History of North American Pinnipeds. A Monograph of the Walruses, Sea-Lions, Sea-Bears and Seals of North America. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880, s. 456. (ang.).

- ↑ J.A. Allen: Mammalia of southern Patagonia. W: W.B. Scott (red.): Reports of the Princeton University Expeditions to Patagonia, 1896–1899. Cz. 3: Zoölogy. Schweizerbart: 1905, s. 95. (ang.).

- ↑ a b Lydekker 1909 ↓, s. 601.

- ↑ Lydekker 1909 ↓, s. 603.

- ↑ Lydekker 1909 ↓, s. 606.

- ↑ a b G.J.G. Hofmeyr, Mirounga leonina, [w:] The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015, wersja 2022-1 [dostęp 2022-08-15] (ang.).

- ↑ Nazwy polskie za: W. Cichocki, A. Ważna, J. Cichocki, E. Rajska-Jurgiel, A. Jasiński & W. Bogdanowicz: Polskie nazewnictwo ssaków świata. Warszawa: Muzeum i Instytut Zoologii PAN, 2015, s. 154. ISBN 978-83-88147-15-9. (pol. • ang.).

- ↑ a b c D.E. Wilson & D.M. Reeder (redaktorzy): Species Mirounga leonina. [w:] Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (Wyd. 3) [on-line]. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. [dostęp 2021-11-03].

- ↑ a b C.J. Burgin, D.E. Wilson, R.A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands, T.E. Lacher & W. Sechrest: Illustrated Checklist of the Mammals of the World. Cz. 2: Eulipotyphla to Carnivora. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 2020, s. 442. ISBN 978-84-16728-35-0. (ang.).

- ↑ T.S. Palmer. Index Generum Mammalium: a List of the Genera and Families of Mammals. „North American Fauna”. 23, s. 428, 1904. (ang.).

- ↑ Ling i Bryden 1992 ↓, s. 5.

- ↑ a b B. Stewart: Family Phocidae (Earless Seals). W: D.E. Wilson & R.A. Mittermeier (redaktorzy): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Cz. 4: Sea Mammals. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 2014, s. 170. ISBN 978-84-96553-93-4. (ang.).

- ↑ Ling i Bryden 1992 ↓, s. 2.

- ↑ Elephant Seal Travels 18,000 Miles. ScienceDaily, 2011-12-13. [dostęp 2012-05-27].

- ↑ Ocean Warming Causes Elephant Seals to Dive Deeper. ScienceDaily, 2012-02-09. [dostęp 2012-05-27].

- ↑ Hauswirth, M.: Mirounga leonina. Animal Diversity Web, 2020. [dostęp 2021-11-03]. (ang.).

Bibliografia

[edytuj | edytuj kod]- H.D. de Blainville. Sur quelques cranes de phoques. „Journal de Physique, de Chimie, d’Histoire Naturelle et des Arts”. 91, s. 286–300, 1820. (fr.).

- R. Lydekker. On the skull-characters in the southern sea-elephant. „Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London”. 1909 (3), s. 600–606, 1909. (ang.).

- J.K. Ling & M.M. Bryden. Mirounga leonina. „Mammalian Species”. 391, s. 1–8, 1992. DOI: 10.2307/3504169. (ang.).