Choroba Alzheimera: Różnice pomiędzy wersjami

| [wersja przejrzana] | [wersja nieprzejrzana] |

uzupełniłem leki z memantyną zarejestrowane w Polsce |

z http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alzheimer%27s_disease |

||

| Linia 1: | Linia 1: | ||

{{Redirect|Alzheimer}} |

|||

{{Choroba infobox |

|||

{{pp-semi|small=yes}}{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

|nazwa = Choroba Alzheimera |

|||

{{Infobox disease |

|||

|nazwa łacińska = |

|||

|Name=Alzheimer's disease |

|||

|grafika = |

|||

|Image=Alzheimer's_disease_brain_comparison.jpg |

|||

|podpis grafiki = |

|||

|Caption=Comparison of a normal aged brain (left) and the brain of a person with Alzheimer's (right). Differential characteristics are pointed out. |

|||

|ICD10 = G30 |

|||

|DiseasesDB=490 |

|||

|ICD10 nazwa = |

|||

|ICD10={{ICD10|G|30||g|30}}, {{ICD10|F|00||f|00}} |

|||

|ICD10.0 = Choroba Alzheimera o wczesnym początku |

|||

|ICD9={{ICD9|331.0}}, {{ICD9|290.1}} |

|||

|ICD10.1 = Choroba Alzheimera o późnym początku |

|||

|ICDO= |

|||

|ICD10.2 = |

|||

|OMIM=104300 |

|||

|ICD10.3 = |

|||

|MedlinePlus=000760 |

|||

|ICD10.4 = |

|||

|eMedicineSubj=neuro |

|||

|ICD10.5 = |

|||

|eMedicineTopic=13 |

|||

|ICD10.6 = |

|||

|MeshID=D000544 |

|||

|ICD10.7 = |

|||

|GeneReviewsNBK=NBK1161 |

|||

|ICD10.8 = Otępienie typu alzheimerowskiego |

|||

|}} |

|||

|ICD10.9 = Inne określone choroby zwyrodnieniowe układu nerwowego |

|||

'''Alzheimer's disease''' ('''AD'''), also known in medical literature as '''Alzheimer disease''', is the most common form of [[dementia]]. There is no cure for the disease, which [[degenerative disease|worsens as it progresses]], and eventually leads to [[Terminal illness|death]]. It was first described by German psychiatrist and neuropathologist [[Alois Alzheimer]] in 1906 and was named after him.<ref name="pmid9661992"/> Most often, AD is diagnosed in people over 65 years of age,<ref>{{vcite journal|author=Brookmeyer R., Gray S., Kawas C. |title=Projections of Alzheimer's disease in the United States and the public health impact of delaying disease onset |journal=[[American Journal of Public Health]] |volume=88 |issue=9 |pages=1337–42 |year=1998 |month=September |pmid=9736873 |pmc=1509089 |doi=10.2105/AJPH.88.9.1337}}</ref> although the less-prevalent [[early-onset Alzheimer's]] can occur much earlier. In 2006, there were {{Nowrap|26.6 million}} sufferers worldwide. Alzheimer's is predicted to affect 1 in 85 people globally by 2050.<ref name="Brookmeyer2007"/> |

|||

|DSM nazwa = |

|||

|DSM nazwa łacińska = |

|||

|DSM = |

|||

|ICDO = |

|||

|DiseasesDB = |

|||

|OMIM = |

|||

|MedlinePlus = |

|||

|MeshID = |

|||

|MeshYear = |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Choroba infobox |

|||

|nazwa = Otępienie w chorobie Alzheimera |

|||

|nazwa łacińska = |

|||

|grafika = |

|||

|podpis grafiki = |

|||

|ICD10 = F00 |

|||

|ICD10 nazwa = |

|||

|ICD10.0 = Otępienie w chorobie Alzheimera z wczesnym początkiem |

|||

|ICD10.1 = Otępienie w chorobie Alzheimera z późnym początkiem |

|||

|ICD10.2 = Otępienie atypowe lub mieszane w chorobie Alzheimera |

|||

|ICD10.3 = |

|||

|ICD10.4 = |

|||

|ICD10.5 = |

|||

|ICD10.6 = |

|||

|ICD10.7 = |

|||

|ICD10.8 = |

|||

|ICD10.9 = Otępienie w chorobie Alzheimera, nieokreślone |

|||

|DSM nazwa = |

|||

|DSM nazwa łacińska = |

|||

|DSM = |

|||

|ICDO = |

|||

|DiseasesDB = 29283 |

|||

|OMIM = |

|||

|MedlinePlus = 000739 |

|||

|MeshID = D003704 |

|||

|MeshYear = 2010 |

|||

}} |

|||

[[Plik:Alzheimer dementia (3) presenile onset.jpg|thumb|Obraz histopatologiczny płytek starczych w korze mózgu pacjenta z chorobą Alzheimera o początku przed okresem starzenia. Barwienie srebrem]] |

|||

'''Choroba Alzheimera''' (łac. ''Morbus Alzheimer'', ang. ''Alzheimer's disease'') – postępująca, [[choroby neurodegeneracyjne|degeneracyjna choroba]] [[ośrodkowy układ nerwowy|ośrodkowego układu nerwowego]], charakteryzująca się występowaniem [[Otępienie|otępienia]]. |

|||

Although Alzheimer's disease develops differently for every individual, there are many common symptoms.<ref name="alzheimers.org">{{cite web|title=What is Alzheimer's disease? |url=http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/documents_info.php?documentID=100 |publisher=Alzheimers.org.uk |year=2007 |month=August |accessdate=2008-02-21}}</ref> Early symptoms are often mistakenly thought to be 'age-related' concerns, or manifestations of [[Stress (biological)|stress]].<ref name="pmid17222085">{{vcite journal|author=Waldemar G |title=Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer's disease and other disorders associated with dementia: EFNS guideline |journal=Eur J Neurol |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=e1–26 |year=2007 |month=January |pmid=17222085 |doi=10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01605.x |author-separator=, |author2=Dubois B |author3=Emre M |display-authors=3 |last4=Georges |first4=J. |last5=McKeith |first5=I. G. |last6=Rossor |first6=M. |last7=Scheltens |first7=P. |last8=Tariska |first8=P. |last9=Winblad |first9=B.}}</ref> In the early stages, the most common symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. When AD is suspected, the diagnosis is usually confirmed with tests that evaluate behaviour and [[cognitive tests|thinking abilities]], often followed by a [[neuroimaging|brain scan]] if available.<ref name="alzres">{{cite web|title=Alzheimer's diagnosis of AD |url=http://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/diagnosis/ |publisher=Alzheimer's Research Trust |accessdate=2008-02-29}}</ref> As the disease advances, symptoms can include [[Mental confusion|confusion]], irritability and aggression, [[mood swing]]s, trouble with language, and [[long-term memory]] loss. As the sufferer declines they often withdraw from family and society.<ref name="pmid17222085"/><ref name="pmid17823840">{{vcite journal|author=Tabert MH, Liu X, Doty RL, Serby M, Zamora D, Pelton GH, Marder K, Albers MW, Stern Y, Devanand DP |title=A 10-item smell identification scale related to risk for Alzheimer's disease |journal=Ann. Neurol. |volume=58 |issue=1 |pages=155–160 |year=2005 |pmid=15984022 |doi=10.1002/ana.20533}}</ref> Gradually, bodily functions are lost, ultimately leading to death.<ref name="nihstages">{{cite web|title=About Alzheimer's Disease: Symptoms |url=http://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/topics/symptoms |publisher=National Institute on Aging |accessdate=2011-12-28}}</ref> Since the disease is different for each individual, [[prognosis|predicting how it will affect]] the person is difficult. AD develops for an unknown and variable amount of time before becoming fully apparent, and it can progress undiagnosed for years. On average, the life expectancy following diagnosis is approximately seven years.<ref name="pmid3776457">{{vcite journal|author=Mölsä PK, Marttila RJ, Rinne UK |title=Survival and cause of death in Alzheimer's disease and multi-infarct dementia |journal=Acta Neurol Scand |volume=74 |issue=2 |pages=103–7 |year=1986 |month=August |pmid=3776457 |doi=10.1111/j.1600-0404.1986.tb04634.x}}</ref> Fewer than three percent of individuals live more than fourteen years after diagnosis.<ref name="pmid7793228">{{vcite journal|author=Mölsä PK, Marttila RJ, Rinne UK |title=Long-term survival and predictors of mortality in Alzheimer's disease and multi-infarct dementia |journal=ActaNeurol Scand |volume=91 |issue=3 |pages=159–64 |year=1995 |month=March |pmid=7793228}}</ref> |

|||

Nazwa choroby pochodzi od nazwiska niemieckiego psychiatry i neuropatologa [[Alois Alzheimer|Aloisa Alzheimera]], który opisał tę chorobę w 1906 roku. |

|||

The cause and progression of Alzheimer's disease are not well understood. Research indicates that the disease is associated with [[Senile plaques|plaques]] and [[neurofibrillary tangles|tangles]] in the [[brain]].<ref name="pmid15184601"/> Current treatments only help with the symptoms of the disease. There are no available treatments that stop or reverse the progression of the disease. {{as of |

|||

== Historia == |

|||

|2012}}, more than 1000 [[clinical trials]] have been or are being conducted to find ways to treat the disease, but it is unknown if any of the tested treatments will work.<ref name="CT">{{cite web|url=http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=alzheimer |title=Clinical Trials. Found 1012 studies with search of: alzheimer |accessdate=2011-01-10 |publisher=US National Institutes of Health}}</ref> [[Mental exercise|Mental stimulation]], [[exercise]], and a [[balanced diet]] have been suggested as ways to delay cognitive symptoms (though not brain pathology) in healthy older individuals, but there is no conclusive evidence supporting an effect.<ref name="prevention1">{{cite web|title=More research needed on ways to prevent Alzheimer's, panel finds |url=http://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/announcements/2010/06/more-research-needed-ways-prevent-alzheimers-panel-finds |format=PDF |publisher=National Institute on Aging |accessdate=2008-02-29 |date=2006-08-29}}</ref> |

|||

[[Plik:Auguste D aus Marktbreit.jpg|thumb|Auguste D., pacjentka Aloisa Alzheimera]] |

|||

W 1901 roku niemiecki psychiatra [[Alois Alzheimer]] po raz pierwszy zaobserwował u 51-letniej Augusty D. chorobę nazwaną potem jego nazwiskiem. W jej przypadku pierwszym objawem były urojenia zdrady małżeńskiej. Następnie rozwinęły się postępujące zaburzenia pamięci, orientacji, zubożenie języka i problemy z wykonywaniem wyuczonych czynności. |

|||

Because AD cannot be cured and is degenerative, the sufferer relies on others for assistance. The role of the main [[caregiver]] is often taken by the spouse or a close relative.<ref name="metlife.com">{{cite web|title=The MetLife study of Alzheimer's disease: The caregiving experience |month=August |year=2006 |publisher=MetLife Mature Market Institute |format=PDF |accessdate=2011-02-05 |url=http://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/studies/mmi-alzheimers-disease-caregiving-experience-study.pdf | archiveurl= http://web.archive.org/web/20110108073750/http://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/studies/mmi-alzheimers-disease-caregiving-experience-study.pdf | archivedate= 8 January 2011 <!--DASHBot--> | deadurl= no}}</ref> Alzheimer's disease is known for [[caregiving and dementia|placing a great burden on caregivers]]; the pressures can be wide-ranging, involving social, psychological, physical, and economic elements of the caregiver's life.<ref name="pmid17662119">{{vcite journal|author=Thompson CA, Spilsbury K, Hall J, Birks Y, Barnes C, Adamson J |title=Systematic review of information and support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia |journal=BMC Geriatr |volume=7 |page=18 |year=2007 |pmid=17662119 |pmc=1951962 |doi=10.1186/1471-2318-7-18}}</ref><ref name="pmid10489656">{{vcite journal|author=Schneider J, Murray J, Banerjee S, Mann A |title=EUROCARE: a cross-national study of co-resident spouse carers for people with Alzheimer's disease: I—Factors associated with carer burden |journal=International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry |volume=14 |issue=8 |pages=651–661 |year=1999 |month=August |pmid=10489656 |doi=10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199908)14:8<651::AID-GPS992>3.0.CO;2-B}}</ref><ref name="pmid10489657">{{vcite journal|author=Murray J, Schneider J, Banerjee S, Mann A |title=EUROCARE: a cross-national study of co-resident spouse carers for people with Alzheimer's disease: II—A qualitative analysis of the experience of caregiving |journal=International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry |volume=14 |issue=8 |pages=662–667 |year=1999 |month=August |pmid=10489657 |doi=10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199908)14:8<662::AID-GPS993>3.0.CO;2-4}}</ref> In [[developed country|developed countries]], AD is one of the most costly diseases to society.<ref name="pmid15685097">{{vcite journal|author=Bonin-Guillaume S, Zekry D, Giacobini E, Gold G, Michel JP |title=Impact économique de la démence (English: The economical impact of dementia) |language=French |journal=Presse Med |issn=0755-4982 |volume=34 |issue=1 |pages=35–41 |year=2005 |month=January |pmid=15685097}}</ref><ref name="pmid9543467">{{vcite journal|author=Meek PD, McKeithan K, Schumock GT |title=Economic considerations in Alzheimer's disease |journal=Pharmacotherapy |volume=18 |issue=2 Pt 2 |pages=68–73; discussion 79–82 |year=1998 |pmid=9543467}}</ref> |

|||

Po trzech latach choroby pacjentka nie rozpoznawała członków swojej rodziny i siebie, nie była w stanie żyć samodzielnie i musiała zostać umieszczona w specjalnym zakładzie dla umysłowo chorych we Frankfurcie. Alzheimer śledził przebieg jej choroby aż do jej śmierci w 1906 roku, 4 i pół roku od początkowych objawów. Wkrótce dr Alzheimer przedstawił przypadek Augusty D. na forum medycznym i opublikował wyniki swoich badań. Określenia „choroba Alzheimera” użył po raz pierwszy [[Emil Kraepelin]] w swoim ''Podręczniku psychiatrii'' z 1910 roku. |

|||

{{TOC limit|3}} |

|||

== |

==Characteristics== |

||

The disease course is divided into four stages, with progressive patterns of [[cognitive]] and [[functional symptom|functional]] [[Disability|impairments]]. |

|||

Jest to najczęstsza przyczyna występowania otępienia u osób powyżej 65 roku życia. Ocenia się{{kto}}, że na świecie choruje na chorobę Alzheimera ok. 30 mln osób, w Polsce ok. 200 tys. Ze względu na starzenie się społeczeństw w krajach uprzemysłowionych zakłada się, że liczba chorych do roku 2050 potroi się. |

|||

===Pre-dementia=== |

|||

Początek choroby występuje zwykle po 65 roku życia. Przed 65 rokiem życia zachorowania na chorobę Alzheimera stanowią mniej niż 1% przypadków<ref name="Merritt's neurology / edited by Lewis P. Rowland">{{Cytuj książkę | nazwisko=Rowland | imię=Lewis P. | autor link=Lewis P. Rowland | tytuł=Merritt's neurology / edited by Lewis P. Rowland | data=2005 | wydawca=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins | miejsce=Philadelphia | isbn=978-0-7817-5311-1 | strony=}}</ref>. Badania epidemiologiczne stwierdzają, że zapadalność na chorobę Alzheimera wzrasta z wiekiem – u osób po 65 roku życia stwierdza się ją u ok. 14%, a po 80 roku życia w ok. 40%. Po 85 roku życia częstość otępienia naczyniopochodnego zwiększa się w porównaniu z chorobą Alzheimera wśród chorych z otępieniem<ref name="szczeklik">{{Cytuj książkę | autor = Szczeklik Andrzej (red) | tytuł = Choroby wewnętrzne : stan wiedzy na rok 2010 | data = 2010 | wydawca = Medycyna Praktyczna | miejsce = Kraków | isbn = 978-83-7430-255-5 | strony = 1951–1955}}</ref>. |

|||

The first symptoms are often mistakenly attributed to [[ageing]] or [[Stress (biological)|stress]].<ref name="pmid17222085"/> Detailed [[neuropsychological test]]ing can reveal mild cognitive difficulties up to eight years before a person fulfils the clinical criteria for [[diagnosis]] of AD.<ref name="pmid15324363">{{vcite journal|author=Bäckman L, Jones S, Berger AK, Laukka EJ, Small BJ |title=Multiple cognitive deficits during the transition to Alzheimer's disease |journal=J Intern Med |volume=256 |issue=3 |pages=195–204 |year=2004 |month=Sep |pmid=15324363 |doi=10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01386.x}}</ref> These early symptoms can affect the most complex [[Activities of daily living|daily living activities]].<ref>{{vcite journal|author=Nygård L |title=Instrumental activities of daily living: a stepping-stone towards Alzheimer's disease diagnosis in subjects with mild cognitive impairment? |journal=Acta Neurol Scand |volume=Suppl |issue=179 |pages=42–6 |year=2003 |month= |pmid=12603250 |doi=10.1034/j.1600-0404.107.s179.8.x}}</ref> The most noticeable deficit is memory loss, which shows up as difficulty in remembering recently learned facts and inability to acquire new information.<ref name="pmid15324363"/><ref name="pmid12603249">{{vcite journal|author=Arnáiz E, Almkvist O |title=Neuropsychological features of mild cognitive impairment and preclinical Alzheimer's disease |journal=Acta Neurol. Scand., Suppl. |volume=179 |pages=34–41 |year=2003 |pmid=12603249 |doi=10.1034/j.1600-0404.107.s179.7.x}}</ref> |

|||

Subtle problems with the [[executive functions]] of [[attention|attentiveness]], [[planning]], flexibility, and [[abstraction|abstract thinking]], or impairments in [[semantic memory]] (memory of meanings, and concept relationships) can also be symptomatic of the early stages of AD.<ref name="pmid15324363"/> [[Apathy]] can be observed at this stage, and remains the most persistent [[neuropsychiatry|neuropsychiatric]] symptom throughout the course of the disease.<ref>{{vcite journal|author=Landes AM, Sperry SD, Strauss ME, Geldmacher DS |title=Apathy in Alzheimer's disease |journal=J Am Geriatr Soc |volume=49 |issue=12 |pages=1700–7 |year=2001 |month=Dec |pmid=11844006 |doi=10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49282.x}}</ref> The preclinical stage of the disease has also been termed [[mild cognitive impairment]],<ref name="pmid12603249"/> but whether this term corresponds to a different diagnostic stage or identifies the first step of AD is a matter of dispute.<ref name="pmid17279076">{{vcite journal|author=Petersen RC |title=The current status of mild cognitive impairment—what do we tell our patients? |journal=Nat Clin Pract Neurol |volume=3 |issue=2 |pages=60–1 |year=2007 |month=February |pmid=17279076 |doi=10.1038/ncpneuro0402}}</ref> |

|||

== Etiopatogeneza == |

|||

Przyczyna warunkująca wystąpienie tej choroby nie jest znana. |

|||

===Early=== |

|||

Na początek wystąpienia objawów i przebieg choroby mają wpływ również czynniki genetyczne, środowiskowe i choroby współistniejące (np. [[choroby układu krążenia]]). |

|||

In people with AD the increasing impairment of learning and memory eventually leads to a definitive diagnosis. In a small portion of them, difficulties with language, executive functions, [[perception]] ([[agnosia]]), or execution of movements ([[apraxia]]) are more prominent than memory problems.<ref name="pmid10653284">{{vcite journal|author=Förstl H, Kurz A |title=Clinical features of Alzheimer's disease |journal=European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience |volume=249 |issue=6 |pages=288–290 |year=1999 |pmid=10653284 |doi=10.1007/s004060050101}}</ref> AD does not affect all memory capacities equally. [[long-term memory|Older memories]] of the person's life ([[episodic memory]]), facts learned ([[semantic memory]]), and [[implicit memory]] (the memory of the body on how to do things, such as using a fork to eat) are affected to a lesser degree than new facts or memories.<ref name="pmid1300219">{{vcite journal|author=Carlesimo GA, Oscar-Berman M |title=Memory deficits in Alzheimer's patients: a comprehensive review |journal=Neuropsychol Rev |volume=3 |issue=2 |pages=119–69 |year=1992 |month=June |pmid=1300219 |doi=10.1007/BF01108841}}</ref><ref name="pmid8821346">{{vcite journal|author=Jelicic M, Bonebakker AE, Bonke B |title=Implicit memory performance of patients with Alzheimer's disease: a brief review |journal=International Psychogeriatrics |volume=7 |issue=3 |pages=385–392 |year=1995 |pmid=8821346 |doi=10.1017/S1041610295002134}}</ref> |

|||

[[primary progressive aphasia|Language problems]] are mainly characterised by a shrinking [[vocabulary]] and decreased word [[fluency]], which lead to a general impoverishment of oral and [[written language]].<ref name="pmid10653284"/><ref name="pmid1856925">{{cite journal |author=Taler V, Phillips NA |title=Language performance in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: a comparative review |journal=J Clin Exp Neuropsychol |volume=30 |issue=5 |pages=501–56 |year=2008 |month=July |pmid=18569251 |doi=10.1080/13803390701550128 |url=}}</ref> In this stage, the person with Alzheimer's is usually capable of communicating basic ideas adequately.<ref name="pmid10653284"/><ref name="pmid1856925"/><ref name="pmid7967534">{{vcite journal|author=Frank EM |title=Effect of Alzheimer's disease on communication function |journal=J S C Med Assoc |volume=90 |issue=9 |pages=417–23 |year=1994 |month=September |pmid=7967534}}</ref> While performing [[fine motor skill|fine motor tasks]] such as writing, drawing or dressing, certain movement coordination and planning difficulties ([[apraxia]]) may be present but they are commonly unnoticed.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> As the disease progresses, people with AD can often continue to perform many tasks independently, but may need assistance or supervision with the most cognitively demanding activities.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> |

|||

Istnieją 2 główne postacie choroby Alzheimera: |

|||

* postać rodzinna (''FAD'' - ang. ''Familial Alzheimer's Disease'', ok. 15% przypadków) |

|||

* postać sporadyczna (''SAD'' - ang. ''Sporadic Alzheimer's Disease'', ok. 85% przypadków |

|||

a każda z nich może mieć jedną z 2 odmian: |

|||

* postać wczesna (''EOAD'', początek przed 65 r.ż.) |

|||

* postać późna (''LOAD'', początek po 65 r.ż.) |

|||

===Moderate=== |

|||

Część przypadków z postaci rodzinnej jest dziedziczona w sposób [[dziedziczenie autosomalne dominujące|autosomalny dominujący]]. |

|||

Progressive deterioration eventually hinders independence, with subjects being unable to perform most common activities of daily living.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> Speech difficulties become evident due to an inability to [[Anomic aphasia|recall vocabulary]], which leads to frequent incorrect word substitutions ([[paraphasia]]s). Reading and writing skills are also progressively lost.<ref name="pmid10653284"/><ref name="pmid7967534"/> Complex motor sequences become less coordinated as time passes and AD progresses, so the risk of falling increases.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> During this phase, memory problems worsen, and the person may fail to recognise close relatives.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> [[Long-term memory]], which was previously intact, becomes impaired.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> |

|||

Behavioural and [[neuropsychiatric]] changes become more prevalent. Common manifestations are [[Wandering (dementia)|wandering]], [[irritability]] and [[labile affect]], leading to crying, outbursts of unpremeditated [[aggression]], or resistance to caregiving.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> [[Sundowning (dementia)|Sundowning]] can also appear.<ref>{{vcite journal|author=Volicer L, Harper DG, Manning BC, Goldstein R, Satlin A |title=Sundowning and circadian rhythms in Alzheimer's disease |journal=Am J Psychiatry |volume=158 |issue=5 |pages=704–11 |year=2001 |month=May |pmid=11329390 |url=http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/158/5/704 |accessdate=2008-08-27 |doi=10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.704}}</ref> Approximately 30% of people with AD develop [[Delusional misidentification syndrome|illusionary misidentifications]] and other [[delusion]]al symptoms.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> Subjects also lose insight of their disease process and limitations ([[anosognosia]]).<ref name="pmid10653284"/> [[Urinary incontinence]] can develop.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> These symptoms create [[Stress (biological)|stress]] for relatives and caretakers, which can be reduced by moving the person from [[home care]] to other [[Nursing home|long-term care facilities]].<ref name="pmid10653284"/><ref name="pmid7806732">{{vcite journal|author=Gold DP, Reis MF, Markiewicz D, Andres D |title=When home caregiving ends: a longitudinal study of outcomes for caregivers of relatives with dementia |journal=J Am Geriatr Soc |volume=43 |issue=1 |pages=10–6 |year=1995 |month=January |pmid=7806732}}</ref> |

|||

Główne czynniki ryzyka wystąpienia choroby Alzheimera: |

|||

* wiek |

|||

* [[Polimorfizm (genetyka)|polimorfizm]] genu ApoE |

|||

* poziom wykształcenia |

|||

* interakcje społeczne i rodzinne{{fakt|data=2012-10}} |

|||

===Advanced=== |

|||

W toku badań wykryto w etiopatogenezie tej choroby przynajmniej 3 postacie jednogenowe zlokalizowane na chromosomach [[chromosom 21|21]] (''[[βAPP]]''), [[chromosom 14|14]] (''[[PS1]]''), [[chromosom 1|1]] (''PS2''). |

|||

During the final stage of AD, the person is completely dependent upon caregivers.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> Language is reduced to simple phrases or even single words, eventually leading to complete loss of speech.<ref name="pmid10653284"/><ref name="pmid7967534"/> Despite the loss of verbal language abilities, people can often understand and return emotional signals.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> Although aggressiveness can still be present, extreme [[apathy]] and [[exhaustion]] are much more common results.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> |

|||

People with AD will ultimately not be able to perform even the simplest tasks without assistance.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> [[musculature|Muscle mass]] and mobility deteriorate to the point where they are bedridden, and they lose the ability to feed themselves.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> AD is a terminal illness, with the cause of death typically being an external factor, such as infection of [[bedsore|pressure ulcers]] or [[pneumonia]], not the disease itself.<ref name="pmid10653284"/> |

|||

==Cause== |

|||

Posiadanie [[Allel|allela]] epsilon 4 (APOE4) genu [[apolipoproteina E]] (''APOE'') ([[chromosom 19|19]]) zwiększa 4-krotnie ryzyko zachorowania, a posiadanie dwóch alleli ponad 20 razy. Oprócz zwiększenia ryzyka zachorowania posiadacze APOE4 w młodości uzyskują więcej punktów w testach na inteligencję, częściej idą na studia (84% posiadaczy APOE4 w porównaniu do 55% posiadaczy nieAPOE4), oraz cierpią na mniejsze zaburzenia w wyniku urazów mózgu. Przypuszcza się więc, że na rozwój choroby może mieć wpływ zbyt intensywna praca komórek nerwowych<ref>[http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20527474.000-a-gene-for-alzheimers-makes-you-smarter.html A gene for Alzheimer's makes you smarter] – 15 II 2010 – New Scientist</ref>. |

|||

[[File:TAU HIGH.JPG|thumb|right|Upright|Microscopic image of a neurofibrillary tangle, conformed by hyperphosphorylated [[tau protein]]]] |

|||

The cause for most Alzheimer's cases is still essentially unknown<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.alz.org/research/science/alzheimers_disease_causes.asp |title=What We Know Today About Alzheimer's Disease |publisher=Alzheimer's Association |accessdate=1 October 2011 |quote=While scientists know Alzheimer's disease involves progressive brain cell failure, the reason cells fail isn't clear.}} |

|||

</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.med.nyu.edu/adc/forpatients/ad.html#causes |title=Alzheimer's Disease: Causes |publisher=NYU Medical Center/NYU School of Medicine |accessdate=30 September 2011 |quote=The cause of Alzheimer's disease is not yet known, but scientists are hoping to find the answers by studying the characteristic brain changes that occur in a patient with Alzheimer's disease. In rare cases when the disease emerges before the age of sixty-five, these brain changes are caused by a genetic abnormality. Scientists are also looking to genetics as well as environmental factors for possible clues to the cause and cure of Alzheimer's disease.}} |

|||

</ref> (except for 1% to 5% of cases where genetic differences have been identified). |

|||

Several competing [[hypotheses]] exist trying to explain the cause of the disease: |

|||

===Cholinergic hypothesis=== |

|||

== Zmiany anatomopatologiczne == |

|||

The oldest, on which most currently available drug therapies are based, is the ''[[cholinergic]] hypothesis'',<ref name="pmid10071091">{{vcite journal|author=Francis PT, Palmer AM, Snape M, Wilcock GK |title=The cholinergic hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: a review of progress |journal=J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. |volume=66 |issue=2 |pages=137–47 |year=1999 |month=February |pmid=10071091 |pmc=1736202 |doi=10.1136/jnnp.66.2.137 |url=}}</ref> which proposes that AD is caused by reduced synthesis of the [[neurotransmitter]] [[acetylcholine]]. The cholinergic hypothesis has not maintained widespread support, largely because medications intended to treat acetylcholine deficiency have not been very effective. Other cholinergic effects have also been proposed, for example, initiation of large-scale aggregation of amyloid,<ref name="pmid15236795">{{vcite journal|author=Shen ZX |title=Brain cholinesterases: II. The molecular and cellular basis of Alzheimer's disease |journal=Med Hypotheses |volume=63 |issue=2 |pages=308–21 |year=2004 |pmid=15236795 |doi=10.1016/j.mehy.2004.02.031}}</ref> leading to generalised neuroinflammation.<ref name="pmid12934968">{{vcite journal|author=Wenk GL |title=Neuropathologic changes in Alzheimer's disease |journal=J Clin Psychiatry |volume=64 Suppl 9 |pages=7–10 |year=2003 |pmid=12934968}}</ref> |

|||

===Amyloid hypothesis=== |

|||

Dochodzi do zaniku [[kora mózgu|kory mózgowej]]. Na poziomie mikroskopowym stwierdza się występowanie blaszek amyloidowych zbudowanych z [[amyloid|beta-amyloidu]] (zwanych też blaszkami starczymi lub płytkami starczymi), które odkładają się w ścianach naczyń krwionośnych. |

|||

In 1991, the ''[[amyloid beta|amyloid]] hypothesis'' postulated that beta-amyloid (βA) deposits are the fundamental cause of the disease.<ref name="pmid1763432">{{vcite journal|author=Hardy J, Allsop D |title=Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease |journal=Trends Pharmacol. Sci. |volume=12 |issue=10 |pages=383–88 |year=1991 |month=October |pmid=1763432 |doi=10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-V}}</ref><ref name="pmid11801334">{{vcite journal|author=Mudher A, Lovestone S |title=Alzheimer's disease-do tauists and baptists finally shake hands? |journal=Trends Neurosci. |volume=25 |issue=1 |pages=22–26 |year=2002 |month=January |pmid=11801334 |doi=10.1016/S0166-2236(00)02031-2}}</ref> Support for this postulate comes from the location of the gene for the [[amyloid precursor protein]] (APP) on [[chromosome 21]], together with the fact that people with [[trisomy 21]] ([[Down Syndrome]]) who have an extra [[gene dosage|gene copy]] almost universally exhibit AD by 40 years of age.<ref name="pmid16904243">{{vcite journal|author=Nistor M |title=Alpha- and beta-secretase activity as a function of age and beta-amyloid in Down syndrome and normal brain |journal=Neurobiol Aging |volume=28 |issue=10 |pages=1493–1506 |year=2007 |month=October |pmid=16904243 |doi=10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.023 |last12=Head |first12=E |author-separator=, |author2=Don M |author3=Parekh M |display-authors=3 |last4=Sarsoza |first4=F. |last5=Goodus |first5=M. |last6=Lopez |first6=G.E. |last7=Kawas |first7=C. |last8=Leverenz |first8=J. |last9=Doran |first9=E.}}</ref><ref name="pmid15639317">{{vcite journal|author=Lott IT, Head E |title=Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome: factors in pathogenesis |journal=Neurobiol Aging |volume=26 |issue=3 |pages=383–89 |year=2005 |month=March |pmid=15639317 |doi=10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.08.005}}</ref> Also, a specific isoform of apolipoprotein, [[APOE4]], is a major genetic risk factor for AD. Whilst apolipoproteins enhance the break down of beta amyloid, some isoforms are not very effective at this task (such as APOE4), leading to excess amyloid buildup in the brain.<ref name="pmid7566000">{{vcite journal|author=Polvikoski T |title=Apolipoprotein E, dementia, and cortical deposition of beta-amyloid protein |journal=N Engl J Med |volume=333 |issue=19 |pages=1242–47 |year=1995 |month=November |pmid=7566000 |doi=10.1056/NEJM199511093331902 |author-separator=, |author2=Sulkava R |author3=Haltia M |display-authors=3 |last4=Kainulainen |first4=Katariina |last5=Vuorio |first5=Alpo |last6=Verkkoniemi |first6=Auli |last7=Niinistö |first7=Leena |last8=Halonen |first8=Pirjo |last9=Kontula |first9=Kimmo}}</ref> Further evidence comes from the finding that [[Genetically modified organism|transgenic]] mice that express a mutant form of the human APP gene develop fibrillar amyloid plaques and Alzheimer's-like brain pathology with spatial learning deficits.<ref>Transgenic mice: |

|||

*{{vcite journal|author=Games D |title=Alzheimer-type neuropathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F beta-amyloid precursor protein |journal=Nature |volume=373 |issue=6514 |pages=523–27 |year=1995 |month=February |pmid=7845465 |doi=10.1038/373523a0 |author-separator=, |author2=Adams D |author3=Alessandrini R |display-authors=3 |last4=Barbour |first4=Robin |last5=Borthelette |first5=Patricia |last6=Blackwell |first6=Catherine |last7=Carr |first7=Tony |last8=Clemens |first8=James |last9=Donaldson |first9=Thomas}} |

|||

*{{vcite journal|author=Masliah E, Sisk A, Mallory M, Mucke L, Schenk D, Games D |title=Comparison of neurodegenerative pathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F beta-amyloid precursor protein and Alzheimer's disease |journal=J Neurosci |volume=16 |issue=18 |pages=5795–811 |year=1996 |month=September |pmid=8795633}} |

|||

*{{vcite journal|author=Hsiao K |title=Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice |journal=Science |volume=274 |issue=5284 |pages=99–102 |year=1996 |month=October |pmid=8810256 |doi=10.1126/science.274.5284.99 |author-separator=, |author2=Chapman P |author3=Nilsen S |display-authors=3 |last4=Eckman |first4=C. |last5=Harigaya |first5=Y. |last6=Younkin |first6=S. |last7=Yang |first7=F. |last8=Cole |first8=G.}} |

|||

*{{vcite journal|author=Lalonde R, Dumont M, Staufenbiel M, Sturchler-Pierrat C, Strazielle C. |title=Spatial learning, exploration, anxiety, and motor coordination in female APP23 transgenic mice with the Swedish mutation |journal=Brain Research (journal) |volume=956 |pages=36–44 |pmid=12426044 |doi=10.1016/S0006-8993(02)03476-5 |year=2002 |issue=1}}</ref> |

|||

An experimental vaccine was found to clear the amyloid plaques in early human trials, but it did not have any significant effect on dementia.<ref name="pmid18640458">{{vcite journal|author=Holmes C |title=Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer's disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial |journal=Lancet |volume=372 |issue=9634 |pages=216–23 |year=2008 |month=July |pmid=18640458 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61075-2 |last12=Nicoll |first12=JA |author-separator=, |author2=Boche D |author3=Wilkinson D |display-authors=3 |last4=Yadegarfar |first4=Ghasem |last5=Hopkins |first5=Vivienne |last6=Bayer |first6=Anthony |last7=Jones |first7=Roy W |last8=Bullock |first8=Roger |last9=Love |first9=Seth}}</ref> Researchers have been led to suspect non-plaque βA [[oligomer]]s (aggregates of many monomers) as the primary pathogenic form of βA. These toxic oligomers, also referred to as amyloid-derived diffusible ligands (ADDLs), bind to a surface receptor on neurons and change the structure of the synapse, thereby disrupting neuronal communication.<ref name="pmid17251419">{{vcite journal|author=Lacor PN |title=Aß Oligomer-Induced Aberrations in Synapse Composition, Shape, and Density Provide a Molecular Basis for Loss of Connectivity in Alzheimer's Disease |journal=Journal of Neuroscience |volume=27 |issue=4 |pages=796–807 |year=2007 |month=January |pmid=17251419 |doi=10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3501-06.2007 |last2=Buniel |first2=MC |last3=Furlow |first3=PW |last4=Clemente |first4=AS |last5=Velasco |first5=PT |last6=Wood |first6=M |last7=Viola |first7=KL |last8=Klein |first8=WL |author-separator=, |display-authors=1}}</ref> |

|||

Obserwuje się także nadmierną agregację [[białko tau|białka tau]] wewnątrz komórek nerwowych mózgu, w postaci [[Splątki neurofibrylarne|splątków neurofibrylarnych]] (NFT). |

|||

One receptor for βA oligomers may be the [[PRNP|prion protein]], the same protein that has been linked to [[Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy|mad cow disease]] and the related human condition, [[Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease]], thus potentially linking the underlying mechanism of these neurodegenerative disorders with that of Alzheimer's disease.<ref name="pmid19242475">{{vcite journal|author=Lauren J |title=Cellular Prion Protein Mediates Impairment of Synaptic Plasticity by Amyloid-β Oligomers |journal=Nature |volume=457 |issue=7233 |pages=1128–32 |year=2009 |month=February |pmid=19242475 |doi=10.1038/nature07761 |pmc=2748841 |author-separator=, |author2=Gimbel D |display-authors=2 |last3=Nygaard |first3=Haakon B. |last4=Gilbert |first4=John W. |last5=Strittmatter |first5=Stephen M.}}</ref> |

|||

In 2009, this theory was updated, suggesting that a close relative of the beta-amyloid protein, and not necessarily the beta-amyloid itself, may be a major culprit in the disease. The theory holds that an amyloid-related mechanism that prunes neuronal connections in the brain in the fast-growth phase of early life may be triggered by ageing-related processes in later life to cause the neuronal withering of Alzheimer's disease.<ref name="Nikolaev">{{vcite journal|author=Nikolaev A, McLaughlin T, O'Leary D, [[Marc Tessier-Lavigne|Tessier-Lavigne M]] |date=19 February 2009 |title=APP binds DR6 to cause axon pruning and neuron death via distinct caspases |journal=Nature |volume=457 |issue=7232 |pages=981–989 |issn=0028-0836 |pmid=19225519 |pmc=2677572 |doi=10.1038/nature07767}} |

|||

== Zapobieganie == |

|||

</ref> N-APP, a fragment of APP from the peptide's [[N-terminus]], is adjacent to beta-amyloid and is cleaved from APP by one of the same enzymes. N-APP triggers the self-destruct pathway by binding to a neuronal receptor called death receptor 6 (DR6, also known as [[TNFRSF21]]).<ref name="Nikolaev"/> DR6 is highly expressed in the human brain regions most affected by Alzheimer's, so it is possible that the N-APP/DR6 pathway might be hijacked in the [[ageing brain]] to cause damage. In this model, beta-amyloid plays a complementary role, by depressing synaptic function. |

|||

Procesowi starzenia nie można zapobiec, ale można go spowolnić. Dowody dotyczące prawdopodobieństwa rozwoju choroby Alzheimera w związku z pewnymi zachowaniami, zwyczajami żywieniowymi, ekspozycją środowiskową oraz chorobami mają różną akceptację w środowisku naukowym<ref>{{Cytuj pismo | nazwisko = Small | imię = Gary W | tytuł = What we need to know about age related memory loss | czasopismo = British Medical Journal | strony = 1502-1507 | data = [[2002-06-22]] | url = | data dostępu = 2006-11-05}}</ref>. |

|||

===Tau hypothesis=== |

|||

=== Czynniki obniżające ryzyko choroby Alzheimera === |

|||

The ''tau hypothesis'' is the idea that [[tau protein]] abnormalities initiate the disease cascade.<ref name="pmid11801334"/> In this model, hyperphosphorylated tau begins to pair with other threads of tau. Eventually, they form [[neurofibrillary tangles]] inside nerve cell bodies.<ref name="pmid1669718">{{vcite journal|author=Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Crowther RA |title=Tau proteins and neurofibrillary degeneration |journal=Brain Pathol |volume=1 |issue=4 |pages=279–86 |year=1991 |month=July |pmid=1669718 |doi=10.1111/j.1750-3639.1991.tb00671.x}}</ref> When this occurs, the [[microtubules]] disintegrate, collapsing the neuron's transport system.<ref name="pmid15615638">{{vcite journal|author=Iqbal K |title=Tau pathology in Alzheimer disease and other tauopathies |journal=Biochim Biophys Acta |volume=1739 |issue=2–3 |pages=198–210 |year=2005 |month=January |pmid=15615638 |doi=10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.09.008 |url= |last12=Grundke-Iqbal |first12=I |author-separator=, |author2=Alonso Adel C |author3=Chen S |display-authors=3 |last4=Chohan |first4=M. Omar |last5=El-Akkad |first5=Ezzat |last6=Gong |first6=Cheng-Xin |last7=Khatoon |first7=Sabiha |last8=Li |first8=Bin |last9=Liu |first9=Fei}}</ref> This may result first in malfunctions in biochemical communication between neurons and later in the death of the cells.<ref name="pmid17127334">{{vcite journal|author=Chun W, Johnson GV |title=The role of tau phosphorylation and cleavage in neuronal cell death |journal=Front Biosci |volume=12 |pages=733–56 |year=2007 |pmid=17127334 |doi=10.2741/2097}}</ref> |

|||

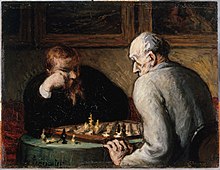

* Podejmowanie czynności intelektualnych (np. gra w szachy lub rozwiązywanie krzyżówek)<ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Verghese J, Lipton R, Katz M, Hall C, Derby C, Kuslansky G, Ambrose A, Sliwinski M, Buschke H | tytuł = Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. | czasopismo = N Engl J Med | rocznik = 348 | wydanie = 25 | strony = 2508-16 | rok = 2003 | id = PMID 12815136}}</ref> |

|||

* Regularne ćwiczenia fizyczne<ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Larson E, Wang L, Bowen J, McCormick W, Teri L, Crane P, Kukull W | tytuł = Exercise is associated with reduced risk for incident dementia among persons 65 roks of age and older. | czasopismo = Ann Intern Med | rocznik = 144 | wydanie = 2 | strony = 73-81 | rok = 2006 | id = PMID 16418406}}</ref> |

|||

* Utrzymywanie regularnych relacji społecznych [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/6332883.stm]. Osoby samotne mają dwukrotnie zwiększone prawdopodobieństwo rozwoju demencji związanej z chorobą Alzheimera w późniejszym wieku niż osoby, które nie były samotne. |

|||

* Dieta śródziemnomorska bogata w warzywa, owoce i z niską zawartością nasyconych tłuszczów<ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Scarmeas N, Stern Y, Mayeux R, Luchsinger J | tytuł = Mediterranean diet, Alzheimer disease, and vascular mediation. | czasopismo = Arch Neurol | rocznik = 63 | wydanie = 12 | strony = 1709-17 | rok = 2006 | id = PMID 17030648}},</ref> uzupełniona w szczególności o: |

|||

** Witaminy z [[Witaminy B|grupy B]]<ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Morris M, Schneider J, Tangney C | tytuł = Thoughts on B-vitamins and dementia. | czasopismo = J Alzheimers Dis | rocznik = 9 | wydanie = 4 | strony = 429-33 | rok = 2006 | id = PMID 16917152}}</ref>, a zwłaszcza w [[kwas foliowy]]<ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Inna I. Kruman1, T. S. Kumaravel2, Althaf Lohani2, Ward A. Pedersen1, Roy G. Cutler1, Yuri Kruman1, Norman Haughey1, Jaewon Lee1, Michele Evans2, and Mark P. Mattson1, 3 | tytuł = Folic Acid Deficiency and Homocysteine Impair DNA Repair in Hippocampal Neurons and Sensitize Them to Amyloid Toxicity in Experimental Models of Alzheimer's Disease . | czasopismo = The Czasopismo of Neuroscience, | rocznik = 22 | wydanie = 5 | rok = March 1, 2002 | strona = http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/content/abstract/22/5/1752?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=&autor1=Kruman&tytułabstract=folic%2Bacid&searchid=1056979885583_2657&stored_search=&IMIĘINDEX=0&czasopismocode=jneuro}} A simplified report can be found at: [http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/Mind_your_head/Common_questions/Medicines_and_supplements/folate.htm www.alzheimers.org.uk]</ref><ref>CBS news, reporting from WebMD [http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2005/08/15/health/webmd/main779484.shtml Folate May Lower Alzheimer's Risk]</ref><ref>[http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/mar2002/nia-01.htm National Institute of Health – Folic Acid Possibly A Key Factor In Alzheimer's Disease Prevention]</ref><ref>[http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2005-08-14-alzheimers-folate_x.htm Alzheimer's and Dementia czasopismo, reported at USA today]</ref> |

|||

** [[Curry]]<ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Giselle P. Lim1, Teresa Chu1, Fusheng Yang, Walter Beech1, Sally A. Frautschy1, and Greg M. Cole1 | tytuł = The Curry Spice Curcumin Reduces Oxidative Damage and Amyloid Pathology in an Alzheimer Transgenic Mouse | czasopismo = The Czasopismo of Neuroscience | rocznik = 21 | wydanie = 4 | strony = 8370-8377 |

|||

| rok = 2001 | id = PMID 11606625}}</ref> |

|||

** Kwasy tłuszczowe [[Kwasy tłuszczowe omega-3|omega-3]], a w szczególności kwasy dokozaheksaenowe<ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Lim W, Gammack J, Van Niekerk J, Dangour A | tytuł = Omega 3 fatty acid for the prevention of dementia. | czasopismo = Cochrane Database Syst Rev | rocznik = | wydanie = | strony = CD005379 | rok = | id = PMID 16437528}}</ref><ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Morris M, Evans D, Tangney C, Bienias J, Wilson R | tytuł = Fish consumption and cognitive decline with age in a large community study. | czasopismo = Arch Neurol | rocznik = 62 | wydanie = 12 | strony = 1849-53 | rok = 2005 | id = PMID 16216930}}</ref> |

|||

** Warzywne i owocowe soki<ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Dai Q, Borenstein A, Wu Y, Jackson J, Larson E | tytuł = Fruit and vegetable juices and Alzheimer's disease: the Kame Project. | czasopismo = Am J Med | rocznik = 119 | wydanie = 9 | strony = 751-9 | rok = 2006 | id = PMID 16945610}}</ref><ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Joseph J, Fisher D, Carey A | tytuł = Fruit extracts antagonize Abeta- or DA-induced deficits in Ca2+ flux in M1-transfected COS-7 cells. | czasopismo = J Alzheimers Dis | rocznik = 6 | wydanie = 4 | strony = 403-11; discussion 443-9 | rok = 2004 | id = PMID 15345811}}</ref> |

|||

** Wysokie dawki witaminy E działającej antyoksydacyjnie (w połączeniu z witaminą C). W przeprowadzonych badaniach przekrojowych wydają się zmniejszać ryzyko choroby Alzheimera, ale nie zmniejszają go w badaniach randomizowanych i obecnie nie są zalecane jako leki zapobiegające, gdyż zaobserwowano, że zwiększają ogólną śmiertelność<ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Petersen R, Thomas R, Grundman M, Bennett D, Doody R, Ferris S, Galasko D, Jin S, Kaye J, Levey A, Pfeiffer E, Sano M, van Dyck C, Thal L | tytuł = Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. | czasopismo = N Engl J Med | rocznik = 352 | wydanie = 23 | strony = 2379-88 | rok = 2005 | id = PMID 15829527}}</ref><ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Zandi P, Anthony J, Khachaturian A, Stone S, Gustafson D, Tschanz J, Norton M, Welsh-Bohmer K, Breitner J | tytuł = Reduced risk of Alzheimer disease in users of antioxidant vitamin supplements: the Cache County Study. | czasopismo = Arch Neurol | rocznik = 61 | wydanie = 1 | strony = 82-8 | rok = 2004 | id = PMID 14732624}}</ref>. |

|||

** Umiarkowane spożycie alkoholu <ref>Scarmeas, N., et al. Mediterranean diet and risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of Neurology, 2006 (published online April 18, 2006). Other research is consistent with the finding that moderate alcohol consumption is associated with lower risk of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia: Mulkamal, K.J., et al. Prospective study of alcohol consumption and risk of dementia in older adults. Czasopismo of the American Medical Association, 2003 (March 19), 289, 1405-1413; Ganguli, M., et al. Alcohol consumption and cognitive function in late life: A longitudinal community study. Neurology, 2005, 65, 1210-12-17; Huang, W., et al. Alcohol consumption and incidence of dementia in a community sample aged 75 roks and older. Czasopismo of Clinical Epidemiology, 2002, 55(10), 959-964; Rodgers, B., et al. Non-linear relationships between cognitive function and alcohol consumption in young, middle-aged and older adults: The PATH Through Life Project. Addiction, 2005, 100(9), 1280-1290; Anstey, K. J., et al. Lower cognitive test scores observed in alcohol are associated with demographic, personality, and biological factors: The PATH Through Life Project. Addiction, 2005, 100(9), 1291-1301; Espeland, M., et al. Association between alcohol intake and domain-specific cognitive function in older women. Neuroepidemiology, 2006, 1(27), 1-12; Stampfer, M.J., et al. Effects of moderate alcohol consumption on cognitive function in women. New England Czasopismo of Medicine, 2005, 352, 245-253; Ruitenberg, A., et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of dementia: the Rotterdam Study. Lancet, 2002, 359(9303), 281-286.</ref> |

|||

* Leki obniżające poziom [[cholesterol|cholesterolu]] ([[statyny]]) zmniejszają ryzyko choroby Alzheimera w badaniach opisowych, ale jak do tej pory nie w badaniach kontrolowanych z [[randomizacja|randomizacją]]<ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Rockwood K | tytuł = Epidemiological and clinical trials evidence about a preventive role for statins in Alzheimer's disease. | czasopismo = Acta Neurol Scand Suppl | rocznik = 185 | wydanie = | strony = 71-7 | rok = | id = PMID 16866914}}</ref>. |

|||

* Według danych Women’s Health Initiative [[hormonalna terapia zastępcza]] nie jest już uważana za czynnik zapobiegający demencji. |

|||

* Długie stosowanie niesterydowych leków przeciwzapalnych (NLPZ) w zmniejszeniu objawów zapalenia stawów i bólu jest związane z obniżeniem prawdopodobieństwa wystąpienia choroby Alzheimera, jak wskazują przeprowadzone badania opisowe<ref>{{Cytuj pismo |autor=Zandi P, Anthony J, Hayden K, Mehta K, Mayer L, Breitner J |tytuł=Reduced incidence of AD with NSAID but not H2 receptor antagonists: the Cache County Study |czasopismo=Neurology |rocznik=59 |wydanie=6 |strony=880-6 |rok=2002 |id=PMID 12297571}}</ref><ref>{{Cytuj pismo |autor=in t' Veld B, Ruitenberg A, Hofman A, Launer L, van Duijn C, Stijnen T, Breteler M, Stricker B |tytuł=Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the risk of Alzheimer's disease |czasopismo=N Engl J Med |rocznik=345 |wydanie=21 |strony=1515-21 |rok=2001 |id=PMID 11794217}}</ref>. Ryzyko związane ze stosowaniem leków zdaje się przeważać korzyści związane ze stosowaniem ich jako pierwotnego środka prewencyjnego<ref name="2006AAGP">{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Lyketsos C, Colenda C, Beck C, Blank K, Doraiswamy M, Kalunian D, Yaffe K | tytuł = Position statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP) regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease. | czasopismo = Am J Geriatr Psychiatry | rocznik = 14 | wydanie = 7 | strony = 561-72 | rok = 2006 | id = PMID 16816009}} [http://ajgp.org/cgi/content/full/14/7/561]</ref>. |

|||

=== |

===Other hypotheses=== |

||

[[Herpes simplex#Alzheimer's disease|Herpes simplex]] virus type 1 has also been proposed to play a causative role in people carrying the susceptible versions of the [[Apolipoprotein E|apoE]] gene.<ref name="pmid18487848">{{vcite journal|author=Itzhaki RF, Wozniak MA |title=Herpes simplex virus type 1 in Alzheimer's disease: the enemy within |journal=J Alzheimers Dis |volume=13 |issue=4 |pages=393–405 |year=2008 |month=May |pmid=18487848 |doi= |issn=1387-2877 |url=http://iospress.metapress.com/openurl.asp?genre=article&issn=1387-2877&volume=13&issue=4&spage=393 |accessdate=2011-02-05}}</ref> |

|||

* zaawansowany wiek |

|||

* genotyp ApoEε4 (w niektórych populacjach) |

|||

* genotyp [[Reelina|reeliny]] |

|||

* urazy głowy<ref>{{Cytuj pismo |autor=Mayeux R, Ottman R, Tang M, Noboa-Bauza L, Marder K, Gurland B, Stern Y |tytuł=Genetic susceptibility and head injury as risk factors for Alzheimer's disease among community-dwelling elderly persons and their name-degree relatives |czasopismo=Ann. Neurol. |rocznik=33 |wydanie=5 |strony=494-501 |rok=1993 |pmid=8498827}}</ref> |

|||

* problemy zdrowotne ze strony układu sercowo-naczyniowego (z powodu [[cukrzyca|cukrzycy]]<ref>{{Cytuj pismo | autor = Kofman OS, MacMillan VH | tytuł = Diffuse Cerebral Atrophy. | czasopismo = Applied Therapeutics | rocznik = 12 | wydanie = 4 | strony = 24-26 | rok = 1970}}</ref>, [[nadciśnienie tętnicze|nadciśnienia tętniczego]]<ref>{{Cytuj pismo |autor=Kehoe P, Wilcock G |tytuł=Is inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system a new treatment option for Alzheimer's disease? |czasopismo=Lancet neurology |rocznik=6 |wydanie=4 |strony=373-8 |rok=2007 |pmid=17362841}}</ref>, [[Hipercholesterolemia|wysokiego poziomu cholesterolu]]<ref>{{Cytuj pismo |autor=Crisby M, Carlson L, Winblad B |tytuł=Statins in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer disease |czasopismo=Alzheimer disease and associated disorders |rocznik=16 |wydanie=3 |strony=131-6 |rok=2002 |pmid=12218642}}</ref> oraz [[udar mózgu|udarów]])<ref>BBC [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/6713163.stm Why stroke ups Alzheimer's risk] 4 June 2007</ref> |

|||

* [[Dym tytoniowy|palenie tytoniu]]<ref>{{Cytuj pismo |autor=Anstey KJ, von Sanden C, Salim A, O'kearney R |tytuł=Smoking as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of prospective studies |czasopismo=Am. J. Epidemiol. |rocznik=166 |wydanie=4 |strony=367-78 |rok=2007 |pmid=17573335 |doi=10.1093/aje/kwm116}}</ref><ref name="Cataldo-2010">{{Cytuj pismo | nazwisko = Cataldo | imię = JK. | nazwisko2 = Prochaska | imię2 = JJ. | nazwisko3 = Glantz | imię3 = SA. | tytuł = Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for Alzheimer's Disease: an analysis controlling for tobacco industry affiliation. | czasopismo = J Alzheimers Dis | wolumin = 19 | numer = 2 | strony = 465-80 | miesiąc = | rok = 2010 | doi = 10.3233/JAD-2010-1240 | pmid = 20110594 }}</ref> |

|||

Another hypothesis asserts that the disease may be caused by age-related [[myelin]] breakdown in the brain. Iron released during myelin breakdown is hypothesised to cause further damage. Homeostatic myelin repair processes contribute to the development of proteinaceous deposits such as beta-amyloid and tau.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Bartzokis G |title=Alzheimer's disease as homeostatic responses to age-related myelin breakdown |journal=Neurobiol. Aging |volume=32 |issue=8 |pages=1341–71 |year=2011 |month=August |pmid=19775776 |pmc=3128664 |doi=10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.08.007 |url=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Mintz J |title=Quantifying age-related myelin breakdown with MRI: novel therapeutic targets for preventing cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease |journal=J. Alzheimers Dis. |volume=6 |issue=6 Suppl |pages=S53–9 |year=2004 |month=December |pmid=15665415 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Mintz J |title=Human brain myelination and beta-amyloid deposition in Alzheimer's disease |journal=Alzheimers Dement |volume=3 |issue=2 |pages=122–5 |year=2007 |month=April |pmid=18596894 |pmc=2442864 |doi=10.1016/j.jalz.2007.01.019 |url=}}</ref> |

|||

* infekcja [[Wirus opryszczki pospolitej|wirusem opryszczki]] (HSV-1)<ref name="pmid18973185">{{Cytuj pismo | autor=Wozniak MA., Mee AP., Itzhaki RF | tytuł=Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA is located within Alzheimer's disease amyloid plaques. | rok=2009 | czasopismo=The Journal of pathology | doi=10.1002/path.2449 | wydanie=217 | wolumin=1 | miesiąc=styczeń | pmid= 18973185 | strony=131–8}}</ref> |

|||

[[Oxidative stress]] and dys-[[homeostasis]] of [[biometal (biology)]] metabolism may be significant in the formation of the pathology.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Su B, Wang X, Nunomura A, ''et al.'' |title=Oxidative stress signaling in Alzheimer's disease |journal=Curr Alzheimer Res |volume=5 |issue=6 |pages=525–32 |year=2008 |month=December |pmid=19075578 |pmc=2780015 |doi=10.2174/156720508786898451 |url=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Kastenholz B, Garfin DE, Horst J, Nagel KA |title=Plant metal chaperones: a novel perspective in dementia therapy |journal=Amyloid |volume=16 |issue=2 |pages=81–3 |year=2009 |pmid=20536399 |doi=10.1080/13506120902879392 |url=}}</ref> |

|||

== Objawy i przebieg choroby == |

|||

W przebiegu choroby dochodzi do wystąpienia następujących objawów: |

|||

* zaburzenia pamięci |

|||

* zmiany nastroju |

|||

* zaburzenia funkcji poznawczych |

|||

* zaburzenia osobowości i zachowania |

|||

AD individuals show 70% loss of [[locus coeruleus]] cells that provide [[norepinephrine]] (in addition to its neurotransmitter role) that locally diffuses from "varicosities" as an endogenous [[antiinflammatory]] agent in the microenvironment around the neurons, glial cells, and blood vessels in the neocortex and hippocampus.<ref name="Heneka">Heneka MT, Nadrigny F, Regen T, Martinez-Hernandez A, Dumitrescu-Ozimek L, Terwel D, Jardanhazi-Kurutz D, Walter J, Kirchhoff F, Hanisch UK, Kummer MP. (2010). [http://www.pnas.org.libproxy.ucl.ac.uk/content/107/13/6058.full.pdf Locus ceruleus controls Alzheimer's disease pathology by modulating microglial functions through norepinephrine.] Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:6058–6063 {{doi|10.1073/pnas.0909586107}} PMID 20231476</ref> It has been shown that norepinephrine stimulates mouse microglia to suppress βA-induced production of cytokines and their [[phagocytosis]] of βA.<ref name="Heneka"/> This suggests that degeneration of the locus ceruleus might be responsible for increased βA deposition in AD brains.<ref name="Heneka"/> |

|||

Charakterystyczne dla demencji (i w tym choroby Alzheimera) objawy to: |

|||

* [[agnozja]] – nieumiejętność rozpoznawania przedmiotów, szczególnie jeżeli chory ma podać nazwę przedmiotu, w odpowiedzi na pytanie zadane z zaskoczenia. |

|||

* [[afazja]] – zaburzenia mowy, jej spowolnienie |

|||

* [[apraksja]] – zaburzenia czynności ruchowych, od prostych do złożonych, np. ubieranie, kąpanie |

|||

==Pathophysiology== |

|||

Zmianom otępiennym mogą towarzyszyć objawy neurologiczne, spośród których najczęstszym jest tzw. zespół parkinsonowski – spowolnienie psychoruchowe, zaburzenia mimiki twarzy i sztywność mięśni<ref>[http://www.forumzdrowia.pl/index.php?id=375&art=1067 Choroba Alzheimera]</ref>. |

|||

{{Main|Biochemistry of Alzheimer's disease}} |

|||

[[File:Alzheimer dementia (3) presenile onset.jpg|thumb|[[Histopathology|Histopathologic]] image of senile plaques seen in the cerebral cortex of a person with Alzheimer's disease of presenile onset. Silver impregnation.]] |

|||

===Neuropathology=== |

|||

W zaawansowanym stadium choroba uniemożliwia samodzielne wykonywanie |

|||

Alzheimer's disease is characterised by loss of [[neuron]]s and [[synapse]]s in the [[cerebral cortex]] and certain subcortical regions. This loss results in gross [[atrophy]] of the affected regions, including degeneration in the [[temporal lobe]] and [[parietal lobe]], and parts of the [[frontal cortex]] and [[cingulate gyrus]].<ref name="pmid12934968"/> Studies using [[magnetic resonance imaging|MRI]] and [[positron emission tomography|PET]] have documented reductions in the size of specific brain regions in people with AD as they progressed from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease, and in comparison with similar images from healthy older adults.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Desikan RS, Cabral HJ, Hess CP, ''et al.'' |title=Automated MRI measures identify individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease |journal=Brain |volume=132 |issue=Pt 8 |pages=2048–57 |year=2009 |month=August |pmid=19460794 |pmc=2714061 |doi=10.1093/brain/awp123 |url=}}</ref><ref>{{vcite journal|author=Moan R |title=MRI software accurately IDs preclinical Alzheimer's disease |journal=Diagnostic Imaging |date=July 20, 2009 |url=http://www.diagnosticimaging.com/news/display/article/113619/1428344}}</ref> |

|||

nawet codziennych prostych czynności i osoba chorująca na chorobę Alzheimera |

|||

wymaga stałej opieki. |

|||

Both [[amyloid plaques]] and [[neurofibrillary tangle]]s are clearly visible by [[microscopy]] in brains of those afflicted by AD.<ref name="pmid15184601">{{vcite journal|author=Tiraboschi P, Hansen LA, Thal LJ, Corey-Bloom J |title=The importance of neuritic plaques and tangles to the development and evolution of AD |journal=Neurology |volume=62 |issue=11 |pages=1984–9 |year=2004 |month=June |pmid=15184601}}</ref> Plaques are dense, mostly [[insoluble]] deposits of [[beta-amyloid]] [[peptide]] and [[Cell (biology)|cellular]] material outside and around neurons. Tangles (neurofibrillary tangles) are aggregates of the microtubule-associated protein tau which has become hyperphosphorylated and accumulate inside the cells themselves. Although many older individuals develop some plaques and tangles as a consequence of ageing, the brains of people with AD have a greater number of them in specific brain regions such as the temporal lobe.<ref name="pmid8038565">{{vcite journal|author=Bouras C, Hof PR, Giannakopoulos P, Michel JP, Morrison JH |title=Regional distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in the cerebral cortex of elderly patients: a quantitative evaluation of a one-year autopsy population from a geriatric hospital |journal=Cereb. Cortex |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=138–50 |year=1994 |pmid=8038565 |doi=10.1093/cercor/4.2.138}}</ref> [[Lewy body|Lewy bodies]] are not rare in the brains of people with AD.<ref name="pmid11816795">{{vcite journal|author=Kotzbauer PT, Trojanowsk JQ, Lee VM |title=Lewy body pathology in Alzheimer's disease |journal=J Mol Neurosci |volume=17 |issue=2 |pages=225–32 |year=2001 |month=Oct |pmid=11816795 |doi=10.1385/JMN:17:2:225}}</ref> |

|||

Czas trwania choroby 6-12 lat, kończy się śmiercią. |

|||

== |

===Biochemistry=== |

||

[[File:Amyloid-plaque formation-big.jpg|300px|thumb|border|Enzymes act on the APP (amyloid precursor protein) and cut it into fragments. The beta-amyloid fragment is crucial in the formation of senile plaques in AD.]] |

|||

Przy ustalaniu rozpoznania choroby bierze się pod uwagę wywiad, informacje zebrane od rodziny i opiekunów, wyniki badania neurologicznego i neuropsychiatryczego, a także badania dodatkowe w tym badania neuroobrazowania. Wiele badań ma na celu wykluczenie innych schorzeń mogących wywoływać podobne zaburzenia pamięci i otępienie. |

|||

Alzheimer's disease has been identified as a [[protein folding|protein misfolding]] disease ([[proteopathy]]), caused by accumulation of abnormally folded [[beta amyloid|amyloid beta]] and [[amyloid tau]] proteins in the brain.<ref name="pmid14528050">{{vcite journal|author=Hashimoto M, Rockenstein E, Crews L, Masliah E |title=Role of protein aggregation in mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases |journal=Neuromolecular Med. |volume=4 |issue=1–2 |pages=21–36 |year=2003 |pmid=14528050 |doi=10.1385/NMM:4:1-2:21}}</ref> Plaques are made up of small [[peptide]]s, 39–43 [[amino acid]]s in length, called [[beta-amyloid]] (Aβ). Beta-amyloid is a fragment from a larger protein called [[amyloid precursor protein]] (APP), a [[transmembrane protein]] that penetrates through the neuron's membrane. APP is critical to neuron growth, survival and post-injury repair.<ref name="pmid16822978">{{vcite journal|author=Priller C, Bauer T, Mitteregger G, Krebs B, Kretzschmar HA, Herms J |title=Synapse formation and function is modulated by the amyloid precursor protein |journal=J. Neurosci. |volume=26 |issue=27 |pages=7212–21 |year=2006 |month=July |pmid=16822978 |doi=10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1450-06.2006}}</ref><ref name="pmid12927332">{{vcite journal|author=Turner PR, O'Connor K, Tate WP, Abraham WC |title=Roles of amyloid precursor protein and its fragments in regulating neural activity, plasticity and memory |journal=Prog. Neurobiol. |volume=70 |issue=1 |pages=1–32 |year=2003 |month=May |pmid=12927332 |doi=10.1016/S0301-0082(03)00089-3}}</ref> In Alzheimer's disease, an unknown process causes APP to be divided into smaller fragments by [[enzymes]] through [[proteolysis]].<ref name="pmid15787600">{{vcite journal|author=Hooper NM |title=Roles of proteolysis and lipid rafts in the processing of the amyloid precursor protein and prion protein |journal=Biochem. Soc. Trans. |volume=33 |issue=Pt 2 |pages=335–8 |year=2005 |month=April |pmid=15787600 |doi=10.1042/BST0330335}}</ref> One of these fragments gives rise to fibrils of beta-amyloid, which form clumps that deposit outside neurons in dense formations known as [[senile plaques]].<ref name="pmid15184601"/><ref name="pmid15004691">{{vcite journal|author=Ohnishi S, Takano K |title=Amyloid fibrils from the viewpoint of protein folding |journal=Cell. Mol. Life Sci. |volume=61 |issue=5 |pages=511–24 |year=2004 |month=March |pmid=15004691 |doi=10.1007/s00018-003-3264-8}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:TANGLES HIGH.jpg|300px|thumb|In Alzheimer's disease, changes in tau protein lead to the disintegration of microtubules in brain cells.]] |

|||

AD is also considered a [[tauopathy]] due to abnormal aggregation of the [[tau protein]]. Every neuron has a [[cytoskeleton]], an internal support structure partly made up of structures called [[microtubules]]. These microtubules act like tracks, guiding nutrients and molecules from the body of the cell to the ends of the [[axon]] and back. A protein called ''tau'' stabilises the microtubules when [[phosphorylation|phosphorylated]], and is therefore called a [[microtubule-associated protein]]. In AD, tau undergoes chemical changes, becoming [[Hyperphosphorylation|hyperphosphorylated]]; it then begins to pair with other threads, creating neurofibrillary tangles and disintegrating the neuron's transport system.<ref name="pmid17604998">{{vcite journal|author=Hernández F, Avila J |title=Tauopathies |journal=Cell. Mol. Life Sci. |volume=64 |issue=17 |pages=2219–33 |year=2007 |month=September |pmid=17604998 |doi=10.1007/s00018-007-7220-x}}</ref> |

|||

Podczas badania klinicznego stosuje się zestaw kryteriów rozpoznania opracowany przez dwie organizacje naukowe zajmujące się chorobą Alzheimera i nazywane ''kryteriami NINCDS-ARDA''. |

|||

===Disease mechanism=== |

|||

=== Badania ośrodkowego układu nerwowego === |

|||

Exactly how disturbances of production and aggregation of the beta-amyloid peptide gives rise to the pathology of AD is not known.<ref name="pmid17622778">{{vcite journal|author=Van Broeck B, Van Broeckhoven C, Kumar-Singh S |title=Current insights into molecular mechanisms of Alzheimer disease and their implications for therapeutic approaches |journal=Neurodegener Dis |volume=4 |issue=5 |pages=349–65 |year=2007 |pmid=17622778 |doi=10.1159/000105156}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Tomografia komputerowa]] (TK) |

|||

<ref>{{vcite journal|author=Huang Y, Mucke L |title=Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies |journal=Cell |volume=148 |issue=6 |pages=1204-22 |year=2012 |pmid= 22424230}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Obrazowanie metodą rezonansu magnetycznego|Rezonans magnetyczny]] (MRI) |

|||

The amyloid hypothesis traditionally points to the accumulation of beta-amyloid [[peptide]]s as the central event triggering neuron degeneration. Accumulation of aggregated amyloid [[fibril]]s, which are believed to be the toxic form of the protein responsible for disrupting the cell's [[calcium]] [[ion]] [[homeostasis]], induces [[programmed cell death]] ([[apoptosis]]).<ref name="pmid2218531">{{vcite journal|author=Yankner BA, Duffy LK, Kirschner DA |title=Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of amyloid beta protein: reversal by tachykinin neuropeptides |journal=Science |volume=250 |issue=4978 |pages=279–82 |year=1990 |month=October |pmid=2218531 |doi=10.1126/science.2218531}}</ref> It is also known that βA selectively builds up in the [[Mitochondrion|mitochondria]] in the cells of Alzheimer's-affected brains, and it also inhibits certain [[enzyme]] functions and the utilisation of [[glucose]] by neurons.<ref name="pmid17424907">{{vcite journal|author=Chen X, Yan SD |title=Mitochondrial Abeta: a potential cause of metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease |journal=IUBMB Life |volume=58 |issue=12 |pages=686–94 |year=2006 |month=December |pmid=17424907 |doi=10.1080/15216540601047767}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Funkcjonalny magnetyczny rezonans jądrowy|fMRI]] |

|||

* [[Spektroskopia MR]] |

|||

* [[Pozytonowa emisyjna tomografia komputerowa]] (PET) |

|||

* [[Badania SPECT|SPECT]] |

|||

Various inflammatory processes and [[cytokine]]s may also have a role in the pathology of Alzheimer's disease. [[Inflammation]] is a general marker of [[Tissue (biology)|tissue]] damage in any disease, and may be either secondary to tissue damage in AD or a marker of an immunological response.<ref name="pmid15681814">{{vcite journal|author=Greig NH |title=New therapeutic strategies and drug candidates for neurodegenerative diseases: p53 and TNF-alpha inhibitors, and GLP-1 receptor agonists |journal=Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. |volume=1035 |pages=290–315 |year=2004 |month=December |pmid=15681814 |doi=10.1196/annals.1332.018 |author-separator=, |author2=Mattson MP |author3=Perry T |display-authors=3 |last4=Chan |first4=SL |last5=Giordano |first5=T |last6=Sambamurti |first6=K |last7=Rogers |first7=JT |last8=Ovadia |first8=H |last9=Lahiri |first9=DK}}</ref> |

|||

=== Badania neurologiczne i neuropsychiatryczne === |

|||

* [[MMSE]] |

|||

* Diagnostyka [[despresja|depresji]] |

|||

Alterations in the distribution of different [[neurotrophic factor]]s and in the expression of their receptors such as the [[brain derived neurotrophic factor]] (BDNF) have been described in AD.<ref>{{vcite journal|author=Tapia-Arancibia L, Aliaga E, Silhol M, Arancibia S |title=New insights into brain BDNF function in normal aging and Alzheimer disease |journal=[[Brain Research Reviews]] |volume=59 |issue=1 |pages=201–20 |year=2008 |month=Nov |pmid=18708092 |doi=10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.07.007}}</ref><ref>{{vcite journal|doi=10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00378.x |author=Schindowski K, Belarbi K, Buée L |title=Neurotrophic factors in Alzheimer's disease: role of axonal transport |journal=[[Genes, Brain and Behavior]] |volume=7 |issue=Suppl 1 |pages=43–56 |year=2008 |month=Feb |pmid=18184369 |pmc=2228393}}</ref> |

|||

=== Badania genetyczne === |

|||

Są wskazane u chorych z wczesnym początkiem zachorowania i rodzinnym występowaniem choroby Alzheimera. |

|||

===Genetics=== |

|||

== Rozpoznanie różnicowe == |

|||

The vast majority of cases of Alzheimer's disease are sporadic, meaning that they are not genetically inherited although some genes may act as risk factors. On the other hand, around 0.1% of the cases are familial forms of [[autosome|autosomal]] dominant (not sex-linked) inheritance, which usually have an onset before age 65.<ref name="pmid16876668">{{vcite journal|author=Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H |title=Alzheimer's disease |journal=Lancet |volume=368 |issue=9533 |pages=387–403 |year=2006 |month=July |pmid=16876668 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7 |url=}}</ref> This form of the disease is known as [[Familial Alzheimer disease|early onset familial Alzheimer's disease]]. |

|||

W rozpoznaniu różnicowym choroby Alzheimera należy wziąć pod uwagę szereg chorób, zespołów chorobowych i stanów chorobowych w przebiegu których zasadniczym objawem jest otępienie. Szczególnie trzeba poszukiwać i wykluczyć obecność stanów potencjalnie poddających się leczeniu (i często wyleczeniu) takich jak: [[Zaburzenia depresyjne|depresja]], przewlekłe [[zatrucie|zatrucia]] (np. lekowe), uszkodzenia OUN w przebiegu zakażeń, choroby tarczycy (niedoczynność), niedobory witaminowe (głównie witaminy B<sub>12</sub> i tiaminy), stany zapalne naczyń OUN i [[wodogłowie normotensyjne|normotensyjne wodogłowie]]. |

|||

Most of autosomal dominant familial AD can be attributed to mutations in one of three genes: [[amyloid precursor protein]] (APP) and [[presenilin]]s 1 and 2.<ref name="pmid18332245">{{vcite journal|author=Waring SC, Rosenberg RN |title=Genome-wide association studies in Alzheimer disease |journal=Arch Neurol |volume=65 |issue=3 |pages=329–34 |year=2008 |month=March |pmid=18332245 |doi=10.1001/archneur.65.3.329}}</ref> Most mutations in the APP and presenilin genes increase the production of a small protein called [[βA]]42, which is the main component of [[senile plaques]].<ref name="pmid8938131">{{vcite journal|author=Selkoe DJ |title=Translating cell biology into therapeutic advances in Alzheimer's disease |journal=Nature |volume=399 |issue=6738 Suppl |pages=A23–31 |year=1999 |month=June |pmid=10392577 |doi=10.1038/19866}}</ref> Some of the mutations merely alter the ratio between βA42 and the other major forms—e.g., βA40—without increasing βA42 levels.<ref name="pmid8938131">{{vcite journal|author=Borchelt DR |title=Familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate βA1-42/1-40 ratio in vitro and in vivo |journal=Neuron |volume=17 |issue=5 |pages=1005–13 |year=1996 |month=Nov |pmid=8938131 |doi=10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80230-5 |type=Original article |last12=Wang |first12=R |last13=Seeger |first13=M |first14=AI |first15=SE |first16=NG |first17=NA |first18=DL |first19=SG |last20=Sisodia |first20=SS |author-separator=, |author2=Thinakaran G |author3=Eckman CB |display-authors=3 |last4=Levey |last5=Gandy |last6=Copeland |last7=Jenkins |last8=Price |last9=Younkin |first4=Michael K. |first5=Frances |first6=Tamara |first7=Cristian-Mihail |first8=Grace |first9=Sophia}}</ref><ref name="pmid17254019">{{vcite journal|author=Shioi J |title=FAD mutants unable to increase neurotoxic Aβ 42 suggest that mutation effects on neurodegeneration may be independent of effects on Abeta |journal=J Neurochem |volume=101 |issue=3 |pages=674–81 |year=2007 |month=May |pmid=17254019 |doi=10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04391.x |author-separator=, |author2=Georgakopoulos A |author3=Mehta P |display-authors=3 |last4=Kouchi |first4=Zen |last5=Litterst |first5=Claudia M |last6=Baki |first6=Lia |last7=Robakis |first7=Nikolaos K}}</ref> This suggests that presenilin mutations can cause disease even if they lower the total amount of βA produced and may point to other roles of presenilin or a role for alterations in the function of APP and/or its fragments other than βA. |

|||

Błędne rozpoznanie choroby Alzheimera można też łatwo postawić u chorujących na inne [[choroby neurodegeneracyjne]] z demencją: [[choroba Picka]], [[choroba Parkinsona]], [[otępienie czołowo-skroniowe]], [[otępienie z ciałami Lewy'ego]], [[choroba Creutzfeldta-Jakoba]] i [[CADASIL]]. |

|||

Most cases of Alzheimer's disease do not exhibit autosomal-dominant inheritance and are termed sporadic AD. Nevertheless genetic differences may act as [[risk factors]]. The best known genetic risk factor is the inheritance of the ε4 [[allele]] of the [[apolipoprotein E]] (APOE).<ref name="pmid8446617">{{vcite journal|author=Strittmatter WJ |title=Apolipoprotein E: high-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease |journal=Proc Natl Acad Sci USA |volume=90 |issue=5 |pages=1977–81 |year=1993 |month=March |pmid=8446617 |pmc=46003 |doi=10.1073/pnas.90.5.1977 |author-separator=, |author2=Saunders AM |author3=Schmechel D |display-authors=3 |last4=Pericak-Vance |first4=M |last5=Enghild |first5=J |last6=Salvesen |first6=GS |last7=Roses |first7=AD}}</ref><ref name="pmid16567625">{{vcite journal|author=Mahley RW, Weisgraber KH, Huang Y |title=Apolipoprotein E4: A causative factor and therapeutic target in neuropathology, including Alzheimer's disease |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=103 |issue=15 |pages=5644–51 |year=2006 |month=April |pmid=16567625 |pmc=1414631 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0600549103}}</ref> Between 40 and 80% of people with AD possess at least one APOEε4 allele.<ref name="pmid16567625"/> The APOEε4 allele increases the risk of the disease by three times in heterozygotes and by 15 times in homozygotes.<ref name="pmid16876668"/> However, this "genetic" effect is not necessarily purely genetic. For example, certain Nigerian populations have no relationship between presence or dose of APOEε4 and incidence or age-of-onset for Alzheimer's disease.<ref name="pmid16434658">{{vcite journal|author=Hall K, Murrell J, Ogunniyi A, Deeg M, Baiyewu O, Gao S, Gureje O, Dickens J, Evans R, Smith-Gamble V, Unverzagt FW, Shen J, Hendrie H |title=Cholesterol, APOE genotype, and Alzheimer disease: an epidemiologic study of Nigerian Yoruba |journal=Neurology |volume=66 |issue=2 |pages=223–227 |year=2006 |month=January |pmid=16434658 |pmc=2860622 |doi=10.1212/01.wnl.0000194507.39504.17}}</ref> |

|||

== Leczenie == |

|||

<ref name="pmid16278853">{{vcite journal|author=Gureje O, Ogunniyi A, Baiyewu O, Price B, Unverzagt FW, Evans RM, Smith-Gamble V, Lane KA, Gao S, Hall KS, Hendrie HC, Murrell JR |title=APOE ε4 is not associated with Alzheimer's disease in elderly Nigerians |journal=Ann Neurol |volume=59 |issue=1 |pages=182–185 |year=2006 |month=January |pmid=16278853 |pmc=2855121 |doi=10.1002/ana.20694}}</ref> Geneticists agree that numerous other genes also act as risk factors or have protective effects that influence the development of late onset Alzheimer's disease,<ref name="pmid18332245"/> but results such as the Nigerian studies and the incomplete [[penetrance]] for all genetic risk factors associated with sporadic Alzheimers indicate a strong role for environmental effects. Over 400 genes have been tested for association with late-onset sporadic AD,<ref name="pmid18332245"/> most with null results.<ref name="pmid16876668"/> |

|||

Dotychczas nie znaleziono leku, cofającego, lub chociaż zatrzymującego postęp choroby. Leczenie farmakologiczne koncentruje się na objawowym leczeniu zaburzeń pamięci i funkcji poznawczych. |

|||

Mutation in the [[TREM2]] gene have been associated with a 3 to 5 times higher risk of developing Alzheimer's disease.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1056/NEJMoa1211103 |title=Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer's disease |year=2012 |last1=Jonsson |first1=Thorlakur |last2=Stefansson |first2=Hreinn |last3=Steinberg |first3=Stacy |last4=Jonsdottir |first4=Ingileif |last5=Jonsson |first5=Palmi V |last6=Snaedal |first6=Jon |last7=Bjornsson |first7=Sigurbjorn |last8=Huttenlocher |first8=Johanna |last9=Levey |first9=Allan I |journal=New England Journal of Medicine |pages= |type=Original article}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1056/NEJMoa1211851 |title=TREM2 variants in Alzheimer's disease |year=2012 |last1=Guerreiro |first1=Rita |last2=Wojtas |first2=Aleksandra |last3=Bras |first3=Jose |last4=Carrasquillo |first4=Minerva |last5=Rogaeva |first5=Ekaterina |last6=Majounie |first6=Elisa |last7=Cruchaga |first7=Carlos |last8=Sassi |first8=Celeste |last9=Kauwe |first9=John S.K. |journal=New England Journal of Medicine |pages= |type=Original article}}</ref> A suggested mechanism of action is that when [[TREM2]] is mutated, white blood cells in the brain are no longer able to control the amount of beta amyloid present. |

|||

=== Leki podnoszące poziom acetylocholiny === |

|||

[[Plik:Donepezil3d.png|thumb|Trójwymiarowy model donepezilu]] |

|||

* [[Inhibitor]]y [[Esterazy cholinowe|acetylocholinoesterazy]] (AchE) – zwiększają poziom ACh poprzez hamowanie jej metabolizmu. Nie wpływają na receptory cholinergiczne. |

|||