Pancernik dziewięciopaskowy

| Dasypus novemcinctus | |||||

| Linnaeus, 1758[1] | |||||

| |||||

| Systematyka | |||||

| Domena | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Królestwo | |||||

| Typ | |||||

| Podtyp | |||||

| Gromada | |||||

| Podgromada | |||||

| Infragromada | |||||

| Rząd | |||||

| Rodzina | |||||

| Rodzaj | |||||

| Podrodzaj | |||||

| Gatunek |

pancernik dziewięciopaskowy | ||||

| |||||

| Podgatunki | |||||

|

| |||||

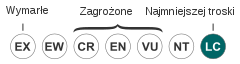

| Kategoria zagrożenia (CKGZ)[36] | |||||

| |||||

| Zasięg występowania | |||||

| |||||

Pancernik dziewięciopaskowy[37], pancernik długoogonowy[38], peba[38], tatusja[38] (Dasypus novemcinctus) – gatunek ssaka lądowego z rodziny pancernikowatych (Dasypodidae). Prowadzi nocny tryb życia. Występuje na obszarze obu Ameryk. Zamieszkuje nory różnorodnych terenów.

Jest jednym z trzymaczy herbu Grenady.

Taksonomia

[edytuj | edytuj kod]Gatunek po raz pierwszy zgodnie z zasadami nazewnictwa binominalnego opisał w 1758 roku szwedzki przyrodnik Karol Linneusz, nadając mu nazwę Dasypus novemcinctus[1]. Miejsce typowe według oryginalnego opisu to „Ameryka Południowa” (w oryg. łac. habitat in America meridionali)[1], ograniczone w 1958 roku do Pernambuco w Brazylii[39][40][41][42]. W 2018 roku na okaz typowy (lektotyp) wyznaczono rycinę Georga Marggrafa, którego cytował Linneusz w swoim oryginalnym opisie[43].

Istnieją sprzeczne doniesienia dotyczące liczby podgatunków; tylko cztery z sześciu podgatunków zostały poparte analizami przeprowadzonymi w XXI wieku[42]. Dane molekularne sugerują, że D. novemcinctus prawdopodobnie reprezentuje wiele ukrytych gatunków, ponieważ nie jest monofiletyczny i utworzył trzy główne klady z Gujany, Ameryki Północnej i Środkowej oraz Ameryki Południowej (który jest parafiletyczny w odniesieniu do D. mazzai i D. sabanicola)[43][44]. Potrzebna jest kompleksowa rewizja taksonomiczna w obrębie gatunku[42].

Autorzy Illustrated Checklist of the Mammals of the World rozpoznają sześć podgatunków[42]. Podstawowe dane taksonomiczne podgatunków (oprócz nominatywnego) przedstawia poniższa tabelka:

| Podgatunek | Oryginalna nazwa | Autor i rok opisu | Miejsce typowe | Holotyp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. n. aequatorialis | Dasypus novemcinctus aequatorialis | Lönnberg, 1913 | Peruchu, na wysokości 7000 ft (2134 m) – 9000 ft (2743 m), Pichincha, Ekwador[44]. | Dorosły samiec[34]. |

| D. n. davisi | Dasypus novemcinctus davisi | Russell, 1953 | Huitzilac, na wysokości 8500 ft (2591 m), Morelos, Meksyk[35]. | Skóra i czaszka dorosłego samca (sygnatura TCWC 4952) ze zbiorów Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collections; okaz zebrany 3 sierpnia 1949 roku przez Williama Davisa[35][45]. |

| D. n. fenestratus | Dasypus fenestratus | W. Peters, 1864 | „Kostaryka”; ograniczone do San José, Kostaryka[46]. | |

| D. n. mexianae | Tatusia novemcincta var. mexianae | Hagmann, 1908 | „Mexiana”[30], tj. Pará, Brazylia[44][46]. | 6 czaszek (2 należące do osobników dorosłych, 4 osobników młodocianych)[30]. |

| D. n. mexicanus | Dasypus novemcinctus var. mexicanus | W. Peters, 1864 | „Meksyk”[22]; ograniczone do Colima, Meksyk[29]. |

Etymologia

[edytuj | edytuj kod]- Dasypus: gr. δασυπους dasupous „włochato-nogi”, od δασυς dasus „włochaty, kudłaty”; πους pous, ποδος podos „stopa”[47].

- novemcinctus: łac. novem „dziewięć”[48]; cinctus „opasany, paskowany”, od cingere „otaczać”[49].

- aequatorialis: późnołac. aequatorialis „równikowy”, od aequator „równik”, od łac. aequare „zrównać się”, od aequus „równy”[50].

- davisi: William Bennoni Davis (1902–1995), amerykański zoolog[51].

- fenestratus: łac. fenestratus „okienny”, od fenestra „okno”[52].

- mexianae: Ilha Mexiana, ujście Amazonki, Pará, Brazylia[53].

- mexicanus: Meksyk[54].

Zasięg występowania

[edytuj | edytuj kod]Pancernik dziewięciopaskowy występuje w Ameryce, zamieszkując w zależności od podgatunku[42]:

- D. novemcinctus novemcinctus – wschodnia Kolumbia, wschodnia i południowa Wenezuela, Gujana, większa część Brazylii, wschodni Ekwador, wschodnie Peru, Boliwia, Paragwaj, Urugwaj oraz północna i środkowo-wschodnia Argentyna; także na wyspach Margarita, Trynidad, Tobago i Grenada.

- D. novemcinctus aequatorialis – zachodnie stoki kolumbijskich Andów do północno-zachodniego Peru.

- D. novemcinctus davisi – zachodni Meksyk, od północnej części stanu Sinaloa na południe do stanu Guerrero.

- D. novemcinctus fenestratus – od Hondurasu na południowy wschód do Panamy (w tym wyspa Barro Colorado) i północnego krańca Ameryki Południowej w północno-wschodniej Kolumbii i północno-zachodniej Wenezueli.

- D. novemcinctus mexianae – delta Amazonki, Pará, Brazylia.

- D. novemcinctus mexicanus – środkowe, południowe i południowo-wschodnie Stany Zjednoczone, wschodni i południowy Meksyk, Belize i Gwatemala.

Występuje również w Salwadorze, lecz nie wiadomo, do którego podgatunku należy[42].

Charakterystyka

[edytuj | edytuj kod]Długość ciała (bez ogona) 360–570 mm, długość ogona (~70% długości ciała) 260–450 mm, długość ucha 25–57 mm, długość tylnej stopy 80–110 mm; masa ciała 3–6 kg[55][56].

Status zagrożenia

[edytuj | edytuj kod]W Czerwonej księdze gatunków zagrożonych Międzynarodowej Unii Ochrony Przyrody i Jej Zasobów został zaliczony do kategorii LC (ang. least concern ‘najmniejszej troski’)[36].

Uwagi

[edytuj | edytuj kod]- ↑ Niepoprawna późniejsza pisownia Dasypus novemcinctus Linnaeus, 1758.

- ↑ Nazwa zajęta przez Dasypus longicaudatus Kerr, 1792.

- ↑ a b Nomen nudum.

- ↑ a b Nazwa zajęta przez Loricatus niger Desmarest, 1804.

- ↑ Nazwa nieważna.

- ↑ Nomen oblitum.

- ↑ Niepoprawna późniejsza pisownia Dasypus uroceras Lund, 1839.

- ↑ Niepoprawna późniejsza pisownia Dasypus peba Desmarest, 1822.

- ↑ Niepoprawna późniejsza pisownia Dasypus longicaudus Wied-Neuwied, 1826.

- ↑ Nazwa zajęta przez Dasypus novemcinctus var. mexicanus W. Peters, 1864.

- ↑ Niepoprawna późniejsza pisownia Tatusia leptorhynchus J.E. Gray, 1873.

Przypisy

[edytuj | edytuj kod]- ↑ a b c C. Linnaeus: Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Wyd. 10. T. 1. Holmiae: Impensis Direct. Laurentii Salvii, 1758, s. 51. (łac.).

- ↑ P. Fermin: Histoire naturelle de la Hollande equinoxiale: ou Déscription des animaux, plantes, fruits, et autres curiosités naturelles, qui se trouvent dans la colonie de Surinam; avec leurs noms différents, tant François, que Latins, Hollandois, Indiens & Négre-Anglois. Amsterdam: M. Magérus, 1765, s. 3. (fr.).

- ↑ P. Fermin: Description générale, historique, géographique et physique de la colonie de Surinam, contenant ce qu’il y a de plus curieux & de plus remarquable, touchant sa situation, ses rivieres, ses forteresses; son gouvernement & sa police; avec les moeurs & les usages des habitants naturels du païs, & des Européens qui y sont établis; ainsi que des eclaircissements sur l’oeconomie générale des esclaves negres, sur les plantations & leurs produits, les arbres fruitiers, les plantes médécinales, & toutes les diverses especes d’animaux qu’on y trouve, &c. Amsterdam: E. van Harrevelt, 1769, s. 110. (fr.).

- ↑ J.Ch.D. von Schreber: Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur, mit Beschreibungen. Erlangen: Expedition des Schreber’schen säugthier- und des Esper’schen Schmetterlingswerkes, 1778, s. ryc. lxxiii. (niem.).

- ↑ R. Kerr: The animal kingdom, or zoological system, of the celebrated Sir Charles Linnæus. Class I. Mammalia: containing a complete systematic description, arrangement, and nomenclature, of all the known species and varieties of the mammalia, or animals which give suck to their young; being a translation of that part of the Systema Naturæ, as lately published, with great improvements, By Professor Gmelin of Goettingen. Edinburgh: Printed for A. Strahan, and T. Cadell, London, and W. Creech, 1792, s. 112. (ang.).

- ↑ A.M.F.J. Palisot de Beauvois: Catalogue raisonné du museum, de Mr. C.W. Peale, membre de la société philosophique de Pensylvanie. Philadelphia: De l’imprimerie de Parent, 1796, s. 18. (fr.).

- ↑ F.M. Daudin: Tableau des divisions, sous-divisions, ordres et genres des mammiferes, Par le Cen Lacépède; Avec Pindication de toutes les especes decrites par Buffon, et leur distribution dans chacun des genres. W: Histoire naturelle par Buffon. Paris: P. Didot et Firmin Didot, 1802, s. 173. (fr.).

- ↑ A.G. Desmarest. Tableau Méthodique des Mammifères. „Nouveau dictionnaire d’histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l’agriculture, à l’économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine, etc. Par une société de naturalistes et d’agriculteurs”. 24, s. 28, 1804. (fr.).

- ↑ J.G. Fischer von Waldheim: Zoognosia tabulis synopticis illustrata, in usum praelectionum Academiae imperialis medico-chirugicae mosquensis edita. Cz. 3. Mosquae: Nicolai S. Vsevolozsky, 1814, s. 128. (łac.).

- ↑ J.K.W. Illiger. Ueberblick der Säugethiere nach ihrer Verbreitung über die Welth. „Abhandlungen der physikalischen Klasse der Königlich-Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften”. 1804–1811, s. 108, 1815. (niem.).

- ↑ von Olfers 1818 ↓, s. 219.

- ↑ von Olfers 1818 ↓, s. 220.

- ↑ M.H.C. Lichtenstein: Das zoologische Museum der Universität zu Berlin. Berlin: Berlin Universität, zoologische Museum, 1818, s. 20. (niem.).

- ↑ A.G. Desmarest: Mammalogie, ou, Description des espèces de mammifères. Cz. 2. Paris: Chez Mme. Veuve Agasse, imprimeur-libraire, 1822, s. 368, seria: Encyclopédie méthodique. (fr.).

- ↑ H.R. Schinz: Naturgeschichte und Abbildungen der Säugethiere: nach den neuesten Systemen zum gemeinnützigen Gebrauche entworfen, und mit Berücksichtigung für den Unterricht der Jugend bearbeitet. Zürich: in Brodtmanns lithographischer Kunstanstalt, 1824, s. 253. (niem.).

- ↑ M. zu Wied-Neuwied: Beiträge zur Naturgeschichte von Brasilien. Weimar: Im Verlage des Landes-Industrie-Comptoirs, 1825, s. 531. (niem.).

- ↑ M.C.H. Lichtenstein. Erläuterungen der nachrichten des Franc. Hernandez von den vierfüfsigen thieren Neuspaniens. „Abhandlungen der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin”. Aus dem Jahre 1827, s. 100, 1830. (niem.).

- ↑ P.W. Lund. Blik paa Brasiliens Dyreverden for sidste Jordomvæltning. Anden Afhandling: Pattedyrene. „Det Kongelige Danske videnskabernes selskabs skrifter. Naturvidenskabelig og mathematisk afdeling”. 2, s. 67, 1839.

- ↑ H. Burmeister. Ueber Dasypus novemcinctus. „Zeitschrift für Zoologie”. 1, s. 199, 1848. (niem.).

- ↑ F. Krauss. Ueber ein neues Gürtelthier aus Surinam. „Archiv für Naturgeschichte”. 28 (1), s. 19, 1862. (niem.).

- ↑ Peters 1865 ↓, s. 179.

- ↑ a b c Peters 1865 ↓, s. 180.

- ↑ L.J.F.J. Fitzinger. Die Natürliche Familie der Gürtheliere (Dasypodes). II. Abtheilung. „Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Classe”. 64, s. 340, 1871. (niem.).

- ↑ R.F. Hensel. Beiträge zue Kenntniss der Säugethiere Süd-Brasiliens. „Abhandlungen der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin”. Aus dem Jahre 1872, s. 105, 1873. (niem.).

- ↑ a b Gray 1873 ↓, s. 14.

- ↑ a b Gray 1873 ↓, s. 15.

- ↑ a b Gray 1873 ↓, s. 16.

- ↑ J.E. Gray. On the Short-tailed Armadillo (Muletia septemcincta). „Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London”. For the year 1874, s. 246, 1874. (ang.).

- ↑ a b V.O. Bailey. Biological survey of Texas. „North American Fauna”. 25, s. 52, 1905. (ang.).

- ↑ a b c G. Hagmann. Die Landsäugetiere der Insel Mexiana. „Archiv für Rassen- und Gesellschafts-Biologie”. 5, s. 29, 1908. (niem.).

- ↑ G.M. Allen. Mammals of the West Indies. „Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College”. 54, s. 195, 1911. (ang.).

- ↑ D.A. Larrañaga: Escritos de Don Dámaso Antonio Larrañaga. Montevideo: Instituto Histórico y Geográfico del Uruguay, 1923, s. 343. (hiszp.).

- ↑ J. Yepes. Una especia nueva de “mulita” (Dasipodinae) para el Norte Argentino. „Physis”. 11, s. 226, 1933. (hiszp.).

- ↑ a b A.J.E. Lönnberg. Mammals from Ecuador and related forms. „Arkiv för zoologi”. 8, s. 34, 1913. (ang.).

- ↑ a b c R.J. Russell. Description of a new armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) from Mexico with remarks on geographic variation of the species. „Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington”. 66, s. 21, 1953. (ang.).

- ↑ a b Dasypus novemcinctus, [w:] The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (ang.).

- ↑ Nazwy polskie za: W. Cichocki, A. Ważna, J. Cichocki, E. Rajska-Jurgiel, A. Jasiński & W. Bogdanowicz: Polskie nazewnictwo ssaków świata. Warszawa: Muzeum i Instytut Zoologii PAN, 2015, s. 24. ISBN 978-83-88147-15-9. (pol. • ang.).

- ↑ a b c K. Kowalski (red.), A. Krzanowski, H. Kubiak, B. Rzebik-Kowalska & L. Sych: Ssaki. Wyd. IV. Warszawa: Wiedza Powszechna, 1991, s. 258, seria: Mały słownik zoologiczny. ISBN 83-214-0637-8.

- ↑ Á. Cabrera. Catalogo del los mamiferos de America del Sur. I (Metatheria – Unguiculata – Carnivora). „Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales "Bernardino Rivadavia" e Institutio Nacional de Investigación de las Ciencias Naturales”. 4 (1), s. 1–307, 1958. (hiszp.).

- ↑ D.E. Wilson & D.M. Reeder (redaktorzy): Species Dasypus novemcinctus. [w:] Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (Wyd. 3) [on-line]. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. [dostęp 2021-06-30].

- ↑ N. Upham, C. Burgin, J. Widness, M. Becker, C. Parker, S. Liphardt, I. Rochon & D. Huckaby: Dasypus septemcinctus Linnaeus, 1758. [w:] ASM Mammal Diversity Database (Version 1.11) [on-line]. American Society of Mammalogists. [dostęp 2023-08-26]. (ang.).

- ↑ a b c d e f C.J. Burgin, D.E. Wilson, R.A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands, T.E. Lacher & W. Sechrest: Illustrated Checklist of the Mammals of the World. Cz. 1: Monotremata to Rodentia. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 2020, s. 122. ISBN 978-84-16728-34-3. (ang.).

- ↑ a b A. Feijó, B.D. Patterson & P. Cordeiro-Estrela. Taxonomic revision of the long-nosed armadillos, Genus Dasypus Linnaeus, 1758 (Mammalia, Cingulata). „PLoS ONE”. 13 (4), s. e0195084, 2018. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195084. (ang.).

- ↑ a b c A. Feijó, J.F. Vilela, J. Cheng, M.A.A. Schetino, R.T.F. Coimbra, C.R. Bonvicino, F.R. Santos, B.D. Patterson & P. Cordeiro-Estrela. Phylogeny and molecular species delimitation of long-nosed armadillos (Dasypus: Cingulata) supports morphology-based taxonomy. „Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society”. 186 (3), s. 813–825, 2019. DOI: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zly091. (ang.).

- ↑ D.J. Schmidly & J.K. Jones Jr.. Holotypes of Recent mammals in Texas natural history collections. „Occasional Papers, Museum of Texas Tech University”. 92, s. 8, 1984. (ang.).

- ↑ a b R.M. Wetzel & E. Mondolfi: The subgenera and species of long-nosed armadillos, genus Dasypus. W: J.F. Eisenberg (red.): Vertebrate Ecology in the Northern Neotropics. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1979, s. 50. ISBN 0-87474-410-5. (ang.).

- ↑ T.S. Palmer. Index Generum Mammalium: a List of the Genera and Families of Mammals. „North American Fauna”. 23, s. 217, 1904. (ang.).

- ↑ Brown 1954 ↓, s. 563.

- ↑ Brown 1954 ↓, s. 204.

- ↑ The Key to Scientific Names ↓, aequatorialis [dostęp 2023-08-26].

- ↑ B. Beolens, M. Watkins & M. Grayson: The Eponym Dictionary of Mammals. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009, s. 102. ISBN 978-0-8018-9304-9. (ang.).

- ↑ The Key to Scientific Names ↓, fenestratus [dostęp 2023-08-26].

- ↑ The Key to Scientific Names ↓, mexianae [dostęp 2023-08-26].

- ↑ The Key to Scientific Names ↓, mexicanus [dostęp 2023-08-26].

- ↑ C. McDonough & J. Loughry: Family Dasypodidae (Long-nosed Armadillos). W: R.A. Mittermeier & D.E. Wilson (redaktorzy): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Cz. 8: Insectivores, Sloths and Colugos. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 2018, s. 44–45. ISBN 978-84-16728-08-4. (ang.).

- ↑ Class Mammalia. W: Lynx Nature Books (A. Monadjem (przedmowa) & C.J. Burgin (wstęp)): All the Mammals of the World. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 2023, s. 79. ISBN 978-84-16728-66-4. (ang.).

Bibliografia

[edytuj | edytuj kod]- I. von Olfers: Bemerkungen zu Illiger’s Überblick der Säugeth-iere nach ihrer Vertheilung über die Welttheile, rücksichtlich der Südamericanischen Arten (Species). W: W.L. von Eschwege: Journal von Brasilien oder vermischte Nachrichten aus Brasilien, auf wissenschaftlichen Reisen gesammelt. Cz. 2. Weimar: Herzoglich Sächsisch Privilegirtes Landes-Industrie-Comptoir, 1818, s. 192–237. (niem.).

- W.C.H. Peters. Über Neue Arten der Säugethiergattungen Geomys, Haplodon und Dasypus. „Monatsberichte der Königlichen Preussische Akademie des Wissenschaften zu Berlin”. Aus dem Jahre 1864, s. 177-181, 1865. (niem.).

- J.E. Gray: Hand-list of the edentate, thick-skinned and ruminant mammals in the British Museum. London: The Trustees, 1873, s. 1–176. (ang.).

- R.W. Brown: Composition of scientific words; a manual of methods and a lexicon of materials for the practice of logotechnics. Washington: Published by the author, 1954, s. 1–882. (ang.).

- The Key to Scientific Names, J.A. Jobling (red.), [w:] Birds of the World, S.M. Billerman et al. (red.), Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca (ang.).