Wikiprojekt:Tłumaczenie artykułów/Irański program nuklearny

Irański program nuklearny został uruchomiony w roku 1950 przy wsparciu Stanów Zjednoczonych jako część programu Atoms for Peace[1]. Wsparcie programu nuklearnego Iranu ze strony Stanów Zjednoczonych oraz państw Europy Zachodniej oraz zachęty ze strony tych państw i ich uczestnictwo w programie trwały do roku 1979, czyli do czasu irańskiej rewolucji islamskiej, w wyniku której doszło do obalenia szacha Mohammada Rezy Pahlawiego[2].

Po rewolucji roku 1979, rząd Iranu częściowo zatrzymał określone elementy programu, po czym przywrócił je przy mniejszym wsparciu państw Zachodu niż przed rewolucją. Irański program nuklearny zakładał wykorzystanie kilku ośrodków badawczych, dwóch kopalni uranu, reaktora jądrowego i zakładów przetwarzania uranu, w tym trzech znanych ośrodków jego wzbogacania.

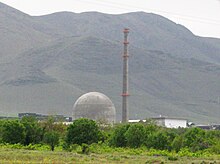

Długo odkładane uruchomienie pierwszej irańskiej elektrowni jądrowej, położonej 17 kilometrów od Buszehru nastąpiło podczas uroczystej ceremonii, 21 sierpnia 2010, choć instalacja nie była aktywna jeszcze w maju 2011. Nie istnieją plany dokończenia prac nad reaktorem „Bushehr II&rdqnuo;, choć przewidywana jest konstrukcja dziewiętnastu elektrowni jądrowych[3] Iran ogłosił, że pracuje nad elektrownią atomową o mocy 360 megawatów, która ma stanąć w Darkhovin, wskazując też na przyszłe plany budowy średniej mocy reaktorów jądrowych oraz kopalń uranu[4].

Przegląd zagadnienia[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Kontrowersje związane z programem nuklearnym Iranu koncentrują się przede wszystkim na domniemanym niepoinformowaniu prze Iran Międzynarodowej Agencji Energii Atomowej o fakcie prowadzenia prac nad wzbogacaniem i przetwarzaniem uranu[5]. Wzbogacać uran można w celu wyprodukowania paliwa do reaktorów atomowych lub – wzbogacając go w wyższym stopniu – w celach wojskowych[6]. Iran twierdzi, ze jego program nuklearny ma charakter pokojowy[7], podając, ze wzbogaca uran do poziomu maksymalnie 5 procent, co zgodne jest z wymaganiami stawianymi paliwu do cywilnych reaktorów jądrowych[8]. Władze państwa twierdzą również, że sekretne działania w kierunku wzbogacania uranu są konsekwencją nacisków ze strony Stanów Zjednoczonych, co przełożyło się na zerwanie kilku kontraktów nuklearnych z innymi państwami((subst:fd}}. Po tym, jak Rada Naczelna Międzynarodowej Agencji Energii Atomowej podała informację o niezgodności działań Iranu z obowiązującymi ustaleniami Radzie Bezpieczeństwa ONZ, Rada zażądała, by Iran zaprzestał wzbogacania uranu[9], zaś prezydent Iranu Mahmud Ahmadineżad określił sankcje jako nielegalne, narzucone przez „aroganckie mocarstwa”m ogłaszając, ze Iran zdecydował o monitorowaniu określanego przez siebie jako pokojowy programu badań nuklearnych z wykorzystaniem „odpowiednich środków prawnych”, czyli Międzynarodowej Agencji Energii Atomowej[10].

Po publicznie wyrażanych oskarżeniach pod adresem Iranu na temat niepowiadomienia o swoich działaniach związanych z materiałami rozszczepialnymi, IAEA rozpoczęła zamknięte w listopadzie 2003 dochodzenie, które stwierdziło, że Iran w sposób systematyczny nie dopełniał zobowiązań wynikających z układu o nierozprzestrzenianiu broni jądrowej, obligujących państwo do zgłaszania swoich działań w IAEA. Agencja nie wykazała jednak dowodów wskazujących na prowadzenie w Iranie prac nad bronią jądrową. Rada Naczelna wstrzymywała się z oficjalnym ogłoszeniem niezgodności do września 2005 i w wyniku rzadko zdarzającej się decyzji niewynikającej z konsensusu zgłosiła ową niezgodność do Rady Bezpieczeństwa Organizacji Narodów Zjednoczonych w lutym 2006. Po ogłoszeniu przez Radę Naczelną IAEA niezgodności działań Iranu z układem ochronnym Radzie Bezpieczeństwa ONZ, zażądała ona od Iranu zaprzestania wzbogacania uranu. Nałożyła też sankcje po odpowiedzi Iranu odmawiającej zastosowania się do żądań Rady. Raport Kongresu Stanów Zjednoczonych z maja 2009 sugeruje, że „Amerykanie, a później również Europejczycy udowodnili oszustwa Iranu, co oznacza, że państwo powinno zrzec się praw do wzbogacania pierwiastków rozszczepialnych, co najprawdopodobniej będzie punktem podnoszonym w negocjacjach z Iranem.”[11]

W zamian za zawieszenie programu wzbogacania uranu, Iranowi zaproponowano „długoterminowy wszechstronny układ, który pozwoli na rozwój stosunków z Iranem i współpracy z nim na podstawie wzajemnego szacunku i ustabilizowaniu międzynarodowej pewności o wyłącznie pokojowym charakterze programu nuklearnego państwa”[12]. Iran jednak konsekwentnie odrzucał możliwość rezygnacji z programu wzbogacania uranu, argumentując, że istnienie programu jest nieodzowne dla bezpieczeństwa energetycznego kraju, jak też, że tego typu ”długoterminowe wszechstronne układy” są z definicji zawodne i doprowadzą do pozbawienia Iranu jego niezbywalnych praw do prowadzenia badań nad technologią nuklearną o przeznaczeniu pokojowym. W roku 2011 trzynaście państw posiadało działające instalacje wzbogacania lub przetwarzania uranu,[13], a kilkanaście następnych wyrażało zainteresowanie rozwinięciem własnych programów wzbogacania pierwiastków radioaktywnych[14]. Pozycja Iranu została poparta przez ruch państw niezaangażowanych, który wyraził swoje obawy o potencjalną monopolizację produkcji paliwa nuklearnego[15].

Odpowiadając na zarzuty, jakoby wzbogacanie uranu prowadzone przez Iran mogłoby prowadzić do wykorzystania paliwa w celach innych niż pokojowe[16], Iran zaproponował wprowadzenie dodatkowych obostrzeń swojego programu nuklearnego, na przykład ratyfikowanie Protokołu Dodatkowego pozwalającego na ostrzejsze inspekcje ze strony IAEA, prowadzenie działań w zakładzie wzbogacania uranu w Natanz jako wielonarodowego centrum paliwowego z udziałem przedstawicieli narodów zewnętrznych, odstąpienie od przetwarzania plutonu i i natychmiastowe przetwarzanie wzbogaconego uranu na pręty paliwowe do reaktorów jądrowych[17]. Irańska oferta otwarcia swego programu wzbogacania uranu na udział instytucji państwowych i prywatnych z całego świata odzwierciedla sugestie komitetu eksperckiego IAEA, powołanego do zbadania metod, które pozwoliłyby na redukcję ryzyka przyczynienia się przetwarzania materiałów radioaktywnych w Iranie do wzrostu wojskowego potencjału nuklearnego kraju[18]. Niektórzy pozarządowi eksperci amerykańscy poparli takie podejście[19][20].Stany Zjednoczone nalegały jednak, by Iran zastosował się do żądań Rady Bezpieczeństwa ONZ, wzywających do zamknięcia programu wzbogacania uranu.

W każdym innym przypadku, gdy Rada Naczelna IAEA odkrywała łamanie zasad bezpieczeństwa polegające na potajemnym wzbogacaniu lub przetwarzaniu materiałów radioaktywnych, rozwiązanie polegało (w przypadku Iraku[21] i Libii[22][23][24]) bądź będzie polegać (w przypadku Korei Północnej[25][26]) na co najmniej zaprzestaniu przetwarzania materiałów radioaktywnych. Według Pierre Goldschmidta, byłego wicedyrektora generalnego i szefa działu bezpieczeństwa IAEA oraz Henry D. Sokolskiego, dyrektora wykonawczego Nonproliferation Policy Education Center, niektóre przypadki niezgodności raportowane przez sekretariat IAEA (Korea Południowa, Egipt) nie były raportowane do Rady Bezpieczeństwa, gdyż Rada Naczelna IAEA nie wydawała oficjalnych dokumentów stwierdzających niezgodności[27][28]. Mimo, że Korea Południowa wzbogacała uran do poziomu bliskiego zastosowaniom wojskowym[29][30]. Korea Południowa stwierdziła, ze z własnej woli zgłaszała swoje działania[29] a Goldschmidt argumentował, że „kwestie polityczne również odgrywały ważną rolę w decyzji Rady” w kwestii niezgłoszenia niezgodności Radzie Bezpieczeństwa ONZ[31].

Historia[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Lata 50. i 60. XX wieku[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Podstawy irańskiego programu nuklearnego powstały po wspieranym przez CIA odsunięciu od władzy wybranego w demokratycznych wyborach premiera Mohammada Mosaddegha i wprowadzeniu na tron pochodzącego z dynastii Pahlawi szacha Mohammada Reza Pahlawiego[32].

Program współpracy nuklearnej w zastosowaniach cywilnych został uruchomiony w ramach amerykańskiego działania „Atoms for Peace”. W roku 1967 uruchomiono działające pod nadzorem Irańskiej Organizacji Energii Atomowej (AEOI) centrum badań nuklearnych w Teheranie (TNRC). Centrum wyposażono w dostarczony przez Stany Zjednoczone pięciomegawatowy reaktor atomowy, uruchomiony w roku 1967 i zasilany wysokowzbogaconym uranem[33][34].

Władze Iranu podpisały traktat o nierozprzestrzenianiu broni jądrowej w roku 1968, ratyfikowały go zaś w roku 1970, co spowodowało, ze prowadzone w kraju badania nad technologiami atomowymi podlegały weryfikacji Międzynarodowej Agencji Energii Atomowej.

Lata 70. XX wieku[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Szach zaaprobował plany skonstruowania z pomocą Stanów Zjednoczonych do 23 elektrowni atomowych do roku 2000[35].

W marcu 1974 Szach przewidywał scenariusz całkowitego wyeksploatowania złóż ropy naftowej i oświadczył: „Benzyna jest materiałem szlachetnym, zbyt cennym, by go palić (...) Przewidujemy produkowanie, tak szybko, jak jest to możliwe, 23 tysięcy megawatów energii elektrycznej za pomocą elektrowni nuklearnych."[36]

Iran, który w tamtych czasach był sojusznikiem Stanów Zjednoczonych, miał duże zasoby finansowe i bliskie stosunki z Waszyngtonem. W takiej sytuacji firmy europejskie walczyły wręcz o możliwość prowadzenia w Iranie interesów[37]. Pierwsza elektrownia jądrowa miała być zlokalizowana w Buszehr i miała dostarczać energii położonemu na lądzie miastu [{Sziraz]]. W roku 1975 mieszcząca się w Bonn firma Kraftwerk Union AG, joint-venture firm Siemens AG i AEG Telefunken podpisała wart pomiędzy 4 a 6 miliardów dolarów kontrakt na budowę elektrowni atomowej wyposażonej w reaktor wodny ciśnieniowy. Konstrukcja dwóch reaktorów atomowych, każdy o mocy 1196 megawatów, została przekazana firmie ThyssenKrupp z przewidywanym czasem ukończenia do roku 1981.

W roku 1973 we Francji powołano spółkę akcyjną Eurodif, zarządzającą zakładem wzbogacania uranu. Założycielami spółki były: Francja, Belgia, Hiszpania i Szwecja. W roku 1975 dziesięcioprocentowy udział Szwecji w Eurodif został przekazany Iranowi w wyniku porozumienia zawartego między Francją a Iranem. Francuska filia Eurodif, Cogéma i rząd Iranu powołały przedsięwzięcie o nazwie Sofidif (Société franco–iranienne pour l'enrichissement de l'uranium par diffusion gazeuse) z 60-procentowym udziałem Francji i 40-procentowym wkładem Iranu. W zamian, Sofidif uzyskał 25% udziałów w Eurodif, co dało dziesięcioprocentowy udział w Eurodif Iranowi. Szach Mohammad Reza Pahlawi pożyczył w roku 1977 na budowę fabryki Eurodif miliard dolarów, udzielając potem jeszcze pożyczki na 180 milionów dolarów, w konsekwencji zyskując prawo do kupna 10% produkcji wybudowanego zakładu.

Prezydent Gerald Ford w roku 1976 podpisał dyrektywę dającą Teheranowi możliwość kupna wybudowanego przez Stany Zjednoczone zakładu wyodrębniającego pluton z paliwa do reaktorów i zarządzania jego działaniami. Umowa przywoływała „kompletny cykl paliwowy”[38]. W tym czasie Szefem Sztabu Białego Domu był Richard Chenney, zaś Sekretarzem Obrony – Donald Rumsfeld. Dokumenty strategii Forda zawierały stwierdzenie, że „wprowadzenie energii nuklearnej zabezpieczy rosnące potrzeby gospodarki irańskiej i uwolni pozostające rezerwy ropy naftowej na rynek eksportowy lub przetworzenie na produkty przemysłu petrochemicznego.”

Ówczesny sekretarz stanu Stanów Zjednoczonych Henry Kissinger wspominał w roku 2005: „Nie przypominam sobie, by w rozmowach pojawił się temat rozpowszechniania broni jądrowej.”[38]. Opublikowana w roku 1974 przez CIA ocena kwestii rozpowszechniania broni jądrowej stwierdzała jednak: „Jeśli [Szach] będzie nadal żył w połowie lat 80. (...) i jeśli kraje trzecie [w szczególności Indie] nadal będą rozwijać arsenały, nie ma wątpliwości, że Iran pójdzie w ich ślady”[39].

Szach podpisał również umowę o współpracy w dziedzinie techniki atomowej z Republiką Południowej Afryki; w jej myśl irańskie wpływy z ropy naftowej finansowały rozwój technologii wzbogacania pierwiastków radioaktywnych w RPA z użyciem procesu „dyszy odrzutowej&rdquo. W zamian Iran otrzymał zapewnienie o dostawach wzbogaconego uranu z RPA oraz Namibii[40].

Po irańskiej rewolucji islamskiej, 1979–1989[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Irańska rewolucja islamska doprowadziła do obalenia autokratycznych rządów Szacha Mohammada Rezy Pahlawiego[41][42][43]. Podczas rewolucji doszło do przejęcia ambasady amerykańskiej przez irańskich studentów[44] i przetrzymywania na jej terenie przez 444 dni (od 4 listopada 1979 do 20 stycznia 1981) amerykańskich dyplomatów[45] W Iranie nastroje antyamerykańskie były podsycane przez wsparcie USA dla represji[46] Szacha i budzącej postrach tajnej policji SAVAK[47], jak też ciągłą urazą pod adresem Stanów Zjednoczonych, związaną ze wsparciem zamachu stanu w roku 1953, który doprowadził do obalenia wyłonionego w demokratycznych wyborach rządu i ustanowienia szacha Pahlawiego jako głowy państwa[48]. Stany Zjednoczone incydent z przetrzymywaniem pracowników dyplomatycznych jako zakładników potraktowały jako pogwałcenie suwerenności placówek dyplomatycznych[49].

Po rewolucji doszło do znacznego osłabienia współpracy międzynarodowej z Iranem na oplu energii nuklearnej. Stany Zjednoczone przestały wypełniać założenia podpisanych z rządem w Teheranie umów, zaś Francja, Niemcy i inne państwa również zmniejszyły swoją współpracę z Iranem pod naciskiem USA. Iran podkreśla, że taki obrót sprawy pokazuje niestabilność współpracy z państwami Zachodu na polu technologii nuklearnej, obciążając Zachód winą za utraconą reputację.

Francja[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Gdy po rewolucji roku 1979 Francja, decyzją prezydenta François Mitterranda z roku 1982 odmówiła przekazywania Iranowi wzbogaconego uranu i gdy Iran nie uzyskał oczekiwanego zwrotu z inwestycji w Eurodif (patrz wyżej), rząd irański wstrzymał swoje płatności pożyczkowe w wysokości miliona USD i próbował uzyskać zwrot udzielonej pożyczki wywołując presję na Francji, na przykład z wykorzystaniem bojówek Hezbollahu, biorących w latach 80. za zakładników francuskich obywateli[potrzebny przypis]. Iranowi odmówiono dostępu do uranu, do którego był uprawniony jako współudziałowiec międzynarodowego zakładu przetwórstwa uranu z uwagi na naciski ze strony Stanów Zjednoczonych[50][51].

Niemcy[edytuj | edytuj kod]

W styczniu 1979 firma Kraftwerk Union pod naciskami Stanów Zjednoczonych[50][52] zatrzymała prace nad elektrownią atomową w Buszehr przy pięćdziesięcioprocentowym zaawansowaniu prac nad jednym reaktorem i oiemdziesięciopięcioprocentowym zaawansowaniem prac nad drugim, w lipcu tego samego roku całkowicie wycofując się z prac. Firma stwierdziła, że jej decyzja była podyktowana niezapłaceniem przez Iran zaległości w wysokości 450 milionów dolarów. Do tego czasu Kraftwerk otrzymał płatności na sumę 2,5 miliarda USD z całej kwoty, na którą opiewał kontrakt. Francuskie przedsiębiorstwo Framatome, filia Arevy również wycofało się z prac[potrzebny przypis]. Iran zapłacił niemieckiemu wykonawcy całość kwoty za wybudowanie dwóch reaktorów w Buszehr[53]. Niemcy wtrzymały prace nad reaktorem w Nuszehr ze względu na naciski amerykańskie[50][54].

W kwietniu 1984 czasopismo „Jane's Defence Weekly” podało, cytując raporty zachodnioniemieckiego wywiadu, mówiące, że Iran jest w stanie w dwa lata skonstruować bombę atomową korzystając z uranu uzyskanego od Pakistanu. Niemcy zamieścili te informacje w pierwszym publicznym zachodnim raporcie wywiadowczym na temat programu prac nad bronią jądrową w porewolucyjnym Iranie[55].

Od 24 marca 1984 do roku 1988 reaktory w Buszehr były wielokrotnie uszkadzane przez naloty sił irackich, a rozwój programu nuklearnego uległ zatrzymaniu. W roku 1984 firma Kraftwerk Union przeprowadziła wstępną ocenę możliwości kontynuacji prac nad projektem elektrowni w Buszehr, lecz zdecydowała o niewłączaniu się w prace z uwagi na wojnę irańsko-iracką.

Stany Zjednoczone[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Stany Zjednoczone wstrzymały dostawy wysoko wzbogaconego uranu dla potrzeb paliwowych ośrodka badawczego w Teheranie, co spowodowało wyłączenie reaktora do czasu, gdy Argentyna zgodziła się dostarczać zamienne paliwo w postaci nisko wzbogaconego uranu[50][51][56].

Stany Zjednoczone po roku 1983 przekonały IAEA do zatrzymania wsparcia irańskiego projektu produkcji wzbogaconego uranu[57].

W kwietniu 1984 Departament Stanu Stanów Zjednoczonych orzekł: „Sądzimy, że dokończenie konstrukcji reaktorów atomowych w Buszehr potrwa co najmniej kolejne dwa do trzech lat.” Rzecznik Departamentu stwierdził również, ze reaktory lekkowodne w Buszehr „ nie są szczególnie przystosowane do prac nad bronią jądrową&rdquo, jak też, że „dodatkowo, nie mamy dowodów na to, by Iran konstruował inne zakłady pozwalające na wyodrębnianie plutonu ze zużytego paliwa jądrowego.”[potrzebny przypis]

W czerwcu 1984 whip senackiej partii mniejszościowej Alan Cranston twierdził, ze Islamska Republika Iranu w ciągu siedmiu lat byłaby w stanie skonstruować własny arsenał jądrowy[58],

Argentyna[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Jak podaje raport argentyńskiego wymiaru sprawiedliwości z roku 2006, w latach 1987-1988 doszło do podpisania trzech umów pomiędzy Iranem a argentyńską Comisión Nacional de Energía Atómica (Narodową Komisją Energii Atomowej). Pierwsza z umów traktowała o argentyńskiej pomocy w przekonwertowaniu teherańskiego reaktora badawczego z jednostki zasilanej wysokowzbogaconym uranem na reaktor zasilany uranem niskowzbogaconym (do wartości 19,75%), jak też o dostawach niskowzbogaconego uranu do Iranu[59]. Dostawa uranu nastąpiła w roku 1993[60]. Umowy druga i trzecia traktowały o wsparciu technicznym, włącznie z dostawami komponentów, podczas budowy pilotażowych zakładów przetwarzania dwutlenku uranu i produkcji paliwa nuklearnego. Pod naciskami Stanów Zjednoczonych doszło do ograniczenia wsparcia wynikającego z drugiej i trzeciej umowy irańsko-argentyńskiej[61].

IAEA[edytuj | edytuj kod]

W roku 1981 przedstawiciele rządu Iranu stwierdzili, ze należy kontynuować prace nad energią jądrową. Przekazywane IAEA raporty zawierały stwierdzenia o tym, jakoby na terenie firmy ENTEC miały odbywać się działania właściwe dla „centrum transferu i rozwoju energii atomowej, jak też przyczyniające się do wzrostu lokalnej wiedzy i siły roboczej niezbędnej do utrzymania przy aktywności ambitnego programu rozwoju technologii reaktorów atomowych i cyklu paliwowego.” IAEA została również poinformowana o istnieniu największego działu ENTEC-u, odpowiedzialnego za testowanie materiałów i fabrykację peletek paliwowych z dwutlenku uranu, jak też o istnieniu działu chemicznego, którego celem była konwersja U3O8 do postaci przemysłowej UO2[62].

W roku 1983 przedstawiciele IAEA wyrażali chęć udzielenia Iranowi pomocy w aspektach chemicznych produkcji paliwa reaktorowego, inżynierii chemicznej i kwestiach projektowych pilotażowych zakładów przetwórstwa uranu, korozji materiałów nuklearnych, produkcji paliwa dla reaktorów lekkowodnych (LWR) i rozwoju pilotażowych zakładów produkcji UO2. IAEA planowała udzielić Iranowi pomocy w dziedzinie produkcji wzbogaconego uranu w ramach własnego programu wsparcia technicznego. Raport Organizacji podawał, ze celem programu było „przyczynienie się do uformowania lokalnej wiedzy i siły roboczej niezbędnej do utrzymania przy aktywności ambitnego programu rozwoju technologii reaktorów atomowych i cyklu paliwowego.”"[62]

Rząd Stanów Zjednoczonych przeprowadził „bezpośrednią interwencję”, by zniechęcić IAEA do wspierania Iranu w produkcji UO2 i UP6. Były urzędnik rządu Stanów Zjednoczonych powiedział, że „program stanął jak wryty”. IAEA zaniechała planów wspierania Iranu w produkcji paliwa nuklearnego i konwersji uranu z uwagi na naciski ze strony USA. Iran w późniejszym czasie ustanowił dwustronną współpracę w dziedzinie paliwa nuklearnego z Chinami, lecz i Chiny zdecydowały o zaniechaniu działań handlowych z Iranem, włącznie z budową zakładu przetwórstwa UP6 ze względu na amerykańskie naciski[62].

Iran[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Iran wysuwał tezy, jakoby zebrane doświadczenia udowadniały, ze zagraniczne instalacje i dostawy paliwa nuklearnego stanowią źródła niepewne[50][63].

Podczas wojny iracko-irańskiej, reaktory w irańskim Buszehr zostały uszkodzone w trakcie ataków samolotów sił irackich i prace nad programem atomowym zostały zatrzymane. Iran powiadomił Międzynarodową Agencję Energii Atomowej o irackich nalotach, wnosząc też skargi na brak działań państw trzecich, jak też na wykorzystywanie w trakcie nalotów rakiet produkcji francuskiej[64][65]

Po rewolucji islamskiej, Iran twierdził też, ze rząd Stanów Zjednoczonych „sprzecznie z umową i jej zobowiązaniami prawnymi” nie zezwalał firmom amerykańskim na „zwrot ponad 2 milionów dolarów zapłaconych przez Iran w czasach sprzed rewolucji.”[66]

Lata 1990–2002[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Od początku lat 90. XX wieku Federacja Rosyjska zawiązała wspólnie z Iranem przedsięwzięcie badawcze o nazwie Persepolis, dające Iranowi dostęp do rosyjskich ekspertów w dziedzinie technologii nuklearnej oraz do informacji wykradzionych z krajów Zachodu przez GRU i Służbę Wywiadu Zagranicznego Rosji, co ujawnił po swym odejściu z GRU Stanislav Lunev[67]. Stwierdził on, że pięć instytucji rosyjskich, w tym Roskosmos pomagały Teheranowi w usprawnieniu posiadanych przezeń rakiet. Wymiana informacji technicznych z Iranem była osobiście zaakceptowana przez dyrektora Służby Wywiadu Zagranicznego Rosji, Wiaczesława Trubnikowa[67]. Prezydent Borys Jelcyn prowadził swego rodzaju „politykę dwutorową” oferując komercyjnie technikę nuklearną rządowi irańskiemu, konsultując przy tym swoje decyzje z rządem amerykańskim[68].

W roku 1990 Iran zaczął poszukiwania partnerów do dalszego rozwoju programu nuklearnego, lecz z uwagi na odmienny klimat polityczny oraz ostre sankcje nakładane przez Stany Zjednoczone, kandydatów do współpracy było niewielu.

W roku 1991 nastąpił przełom w trwającym od roku 1979 impasie francusko-irańskim. Francja zwróciła Iranowi na mocy podpisanego porozumienia kwotę przekraczającą 1,6 miliarda USD. Iran pozostał udziałowcem 25% Eurodifu poprzez Sofidif, francusko-włoskie konsorcjum. Nie upomniał się jednak o wyprodukowany uran[69][70].

W roku 1992, po doniesieniach medialnych o nieogłoszonych przez Iran działaniach związanych z techniką nuklearną, władze w Teheranie zaprosiły do kraju inspektorów IAEA, pozwalając im na inspekcję wszystkich miejsc, o dostęp do których wystąpili. Dyrektor generalny IAEA, Hans Blix, stwierdził później, że wszystkie poddane inspekcji instalacje irańskie były zgodne z pokojowym charakterem wykorzystania energii nuklearnej[71][72]. Inspekcja IAEA objęła swoim zakresem również instalacje atomowe niezgłoszone wcześniej przez władze Iranu, jak też miejsca związane z powstającym projektem wydobycia uranu w Saghand. W tym samym roku, władze Argentyny ujawniły anulowanie sprzedaży cywilnych urządzeń nuklearnych dla Iranu, wartych około 18 milionów USD, co nastąpiło w wyniku nacisków Stanów Zjednoczonych[73].

W roku 1995 Iran podpisał z Rosją kontrakt mający pomóc w dokończeniu prac nad elektrownią w Buszehr[74], a konkretnie opiewający na instalację w budynku Buszehr I reaktora wodnego ciśnieniowego VVER-1000 o mocy 915 MWe, którego konstrukcja miała zakończyć się w roku 2009. Do roku 2011 nie istniały plany dokończenia reaktora dla budynku Bushehr II.

W roku 1996 Stany Zjednoczone przekonały Chińską Republikę Ludową do wypowiedzenia kontraktu na budowę w Iranie zakładu przetwarzania uranu. Chiny udostępniły jednak Iranowi ogólne plany konstrukcji zakładu, zaś władze w Teheranie poinformowały IAEA o zamiarze kontynuowania budowy. Dyrektor IAEA Mohammad El Baradei odwiedził nawet miejsce budowy[75].

Jak podał w swoim raporcie w roku 2006 argentyński wymiar sprawiedliwości, w końcu lat 80. XX wieku i na początku lat 90. Stany Zjednoczone wywierały na Argentynie nacisk, by ta zerwała współpracę w dziedzinach technologii nuklearnych z Iranem. W latach 1994-1994 odbyły się irańsko-argentyńskie negocjacje, mające na celu doprowadzenie do ponownego wejścia w życie trzech podpisanych w latach 1987-1988 umów[61].

Lata 2002–2006[edytuj | edytuj kod]

14 sierpnia 2002 Alireza Jafarzadeh, rzecznik dysydenckiej grupy National Council of Resistance of Iran ujawnił informację o istnieniu dwóch będących na etapie konstrukcji instalacji nuklearnych: zakładu wzbogacania uranu w Natanz (częściowo zlokalizowanego pod powierzchnią ziemi) i zakładów przetwarzania ciężkiej wody w miejscowości Arak. Pojawiła się również sugestia, jakoby agencje wywiadowcze już wiedziały o istnieniu wspomnianych przez Jafarzadeha zakładów, lecz ich raporty zostały utajnione[76].

IAEA natychmiast podjęła kroki zmierzające do uzyskania dostępu do wspomnianych przez Jafarzadeha instalacji, jak też do uzyskania informacji i współpracy w dziedzinie irańskiego programu nuklearnego w jego aktualnym stanie[77]. Jak określały będące wówczas w mocy ustalenia umowy z IAEA o ograniczeniu elementów programu nuklearnego w Iranie[78], Iran nie był zobowiązany do wpuszczania inspektorów agencji do instalacji do sześciu miesięcy przed wprowadzeniem do takiej instalacji paliwa nuklearnego, a nawet do informowania IAEA o powstawaniu nowych zakładów związanych z energią nuklearną. Klauzula mówiąca o sześciomiesięcznym okresie do wprowadzenia materiału radioaktywnego do instalacji była standardowym zapisem dla wszystkich umów IAEA do roku 1992, kiedy to Rada Naczelna zdecydowała, że poszczególne zakłady związane z technologią atomową mają jej być zgłaszane na etapie planowania, nawet przed rozpoczęciem ich budowy. Iran był ostatnim państwem, które zaakceptowało tę zmianę, co nastąpiło dopiero 23 lutego 2003, po rozpoczęciu przez IAEA dochodzenia[79].

Francja, Niemcy i Wielka Brytania (Trójka UE) podjęły działania dyplomatyczne z Iranem, chcąc uzyska odpowiedzi na stawiane pytania o prowadzone przez władze w Teheranie badania nad energią atomową. 21 października 2003 w Teheranie władze Iranu oraz ministrowie spraw zagranicznych Trójki podpisali dokument znany jako Deklaracja Teherańska[80], w myśl którego Iran zobowiązał się do współpracy z IAEA, dobrowolnego podpisania i wprowadzenia Protokołu Dodatkowego jako działania wzmacniającego zaufanie i do zawieszenia na czas negocjacji prac nad wzbogacaniem i przetwarzaniem materiałów radioaktywnych. W zamian, Trójka zadeklarowała uznanie działań nuklearnych Iranu i podjęcie dyskusji nad „zadowalającymi zapewnieniami” dotyczącymi irańskiego programu badań nad technologiami atomowymi, dzięki którym kraj mógłby zyskać łatwiejszy dostęp do nowoczesnych technologii. Iran podpisał Protokół Dodatkowy 18 grudnia 2003 i zgodził się na natychmiastowe wprowadzenie jego ustaleń, czyli składanie raportów w IAEA i umożliwianie inspektorom agencji dostępu do instalacji do czasu ratyfikowania protokołu.

Raport IAEA z 10 listopada 2003 [81] stwierdzał: „jasne jest, że Iran w ciągu dłuższego czasu kilkakrotnie nie dopełniał swoich zobowiązań wynikających z układu z IAEA, szczególnie w dziedzinie raportowania materiałów promieniotwórczych, ich przetwarzania i wykorzystywania, jak też oznajmiania o instalacjach, gdzie takie materiały były przetwarzane i składowane". Iran był zobligowany do poinformowania IAEA o imporcie uranu z Chin i o późniejszym przetwarzaniu i wzbogacaniu materiału, jak też o prowadzonych eksperymentach nad separacją plutonu. Szczegółowa lista punktów, które Iran złamał, co IAEA określiła mianem „wzorcem ukrywania faktów” znajduje się w raporcie Agencji poświęconym irańskiemu programowi nuklearnemu z 15 listopada 2004[82]. Iran przypisuje nieinformowanie o określonych zakupach i działaniach przeszkodom stawianym przez Stany Zjednoczone, które polegały między innymi na wywieraniu nacisku na IAEA, by ta zaprzestała wspierania Iranu w prowadzonym w roku 1983 programie wzbogacania uranu[83][84]. W kwestii tego, czy w Iranie prowadzono w sposób ukryty program o charakterze wojskowym, raport IAEA z listopada 2003 stwierdza, ze nie znaleziono dowodów na to, by wcześniej niezgłoszone Agencji działania były powiązane z programem rozwoju broni atomowej, lecz również, że nie dało się wysnuć wniosku o całkowicie pokojowym charakterze irańskich działań.

W czerwcu 2004 rozpoczęto konstrukcję reaktora wody ciężkiej IR-40 o mocy 40 megawatów

Zgodnie z ustaleniami Umowy Paryskiej[85], 14 listopada 2004 główny negocjator irański w kwestiach atomowych złożył oświadczenie o czasowym dobrowolnym zawieszeniu programu wzbogacania uranu (wzbogacanie nie stanowi naruszenia układu o nierozprzestrzenianiu broni jądrowej) i dobrowolnym wprowadzeniu w życie Protokołu Dodatkowego, jako konsekwencja wywartej na Teheranie presji ze strony Wielkiej Brytanii, Francji i Niemiec, działających w imieniu Unii Europejskiej. Podjęte przez Iran działania miały, jak to określił negocjator, charakter dobrowolnych środków mających doprowadzić do wzmocnienia zaufania. Podjęte działania miały zostać utrzymane w mocy na odpowiednio długi okres (wspominano sześć miesięcy) potrzebny do kontynuowania negocjacji z Unią Europejską. 24 listopada Iran podjął próbę wprowadzenia zmian w warunkach umowy z Unią Europejską, polegającą na wykluczeniu z ograniczeń pewnej ilości sprzętu o przeznaczeniu badawczym. Iran wycofał się z wniosku po czterech dniach. Jak stwierdził Seyyed Hossein Mousavian, jeden z przedstawicieli Iranu w negocjacjach, Iran jasno dał do zrozumienia europejskim partnerom, że nie zamierza w sposób stały zatrzymywać programu wzbogacania uranu.

Przed podpisaniem tekstu [Porozumienia] Paryskiego, Dr Rohani (...) podkreślił, że ani słowem ani w myślach nie możemy dopuścić do zaprzestania naszych działań. Ambasadorzy przekazali jego wiadomość ministrom spraw zagranicznych przed podpisaniem uzgodnionego tekstu porozumienia (...) Irańczycy jasno dali do zrozumienia swoim europejskim partnerom, że jeśli ci będą starali się całkowicie zatrzymać działania nuklearne Iranu, negocjacje zostaną zatrzymane. Europejczycy odpowiedzieli, że nie starają się dopuścić do zatrzymania działań Iranu, lecz chcą zapewnienia, że działania Iranu nie będą dążyły ku celom militarnym[86].

W lutym 2005, Iran zaczął wywierać na Trójce naciski celem przyspieszenia rozmów, czemu przedstawiciele Trójki odmówili„EU rejects Iran call to speed up nuclear talks” Reuters, 1 lutego 2005. 2005-02-01. [dostęp 2009-09-20].</ref>. Rozmowy posuwały się wolno ze względu na różnice zdań stron uczestniczących w negocjacjach[87]. Na początku sierpnia 2005, po czerwcowym wyborze na urząd prezydenta Iranu Mahmouda Ahmadinejada, władze zdjęły zabezpieczenia z urządzeń do wzbogacania uranu znajdujących się w mieście Ishfahan[88], co władze Wielkiej Brytanii określiły mianem „złamania ustaleń porozumienia paryskiego&rdquo[89], choć można argumentować, ze Unia Europejska również naruszyła postanowienia ugody paryskiej poprzez domaganie się, by Iran całkowicie zaprzestał działań wzbogacających uran[90]. Kilkanaście dni później przedstawiciele Trójki zaoferowali Iranowi pakiet rozwiązań w zamian za całkowite zaprzestanie wzbogacania uranu. Pakiet miał zawierać korzyści polityczne, handlowe i nuklearne, jak też zapewnić długoterminowe dostawy paliwa nuklearnego i zapewnienie o nieagresji ze strony Unii Europejskiej (lecz nie ze strony Stanów Zjednoczonych)[89]. Mohammad Saeedi, zastępca przewodniczącego irańskiej organizacji energii atomowej odrzucił ofertę określając ją mianem „niezwykle obraźliwej i poniżającej”[89], zaś niezależni analitycy scharakteryzowali ją jako „puste pudełko[91]”. Irańskie oświadczenie, ze państwo nie zaprzestanie wzbogacania materiałów radioaktywnych nastąpiło na kilkanaście miesięcy przed wyborem na urząd prezydencki Mahmuda Ahmadineżada. Opóźnienie ponownego uruchomienia programu nuklearnego miało pozwolić IAEA na instalację urządzeń monitorujących działania Iranu. Faktyczne ponowne uruchomienie badań nuklearnych zbiegło się w czasie z wyborem Ahmadineżada na urząd prezydenta, jak też z powołaniem na stanowisko głównego negocjatora w kwestiach nuklearnych Ali Larijaniego[92].

Około roku 2005 Niemcy odmówiły eksportowania urządzeń nuklearnych do Iranu, jak też zrefundowania środków, którymi Iran zapłacil za takie urządzenia w latach 80. XX wieku[53].

W sierpniu 2005, przy wsparciu Pakistanu[93] grupa amerykańskich ekspertów rządowych i międzynarodowych przedstawicieli świata nauki stwierdziła, ze śladowe ilości uranu o przeznaczeniu wojskowym odnalezione w Iranie pochodzą z zanieczyszczonych urządzeń pakistańskich i nie stanowią dowodu na prowadzenie przez Iran tajnego programu rozwoju broni atomowej[94]. We wrześniu tego samego roku, dyrektor generalny IAEA Mohammad ElBaradei stwierdził, że większość śladów wysoko wzbogaconego uranu odnaleziona w Iranie przez inspektorów pochodziła z elementów importowanej do kraju centryfugi, potwierdzając wersję Iranu mówiącą o pochodzeniu uranu z zanieczyszczeń. Źródła w Wiedniu i Departamencie Stanu USA stwierdziły, że w perspektywie praktyczniej rozwiązane zostały kwestie wysokowzbogaconego uranu w Iranie[95].

Rada Naczelna IAEA opóźniała ostateczną decyzję w kwestiach irańskich prac nad materiałami rozszczepialnymi przez dwa lata – od roku 2003, na czas współpracy Iranu z przedstawicielami Trójki. 24 września 2005, po złamaniu przez Teheran ustaleń z Paryża, Rada uznała, że Iran działał w niezgodności z ustaleniami pomiędzy Teheranem a IAEA, głównie biorąc pod uwagę fakty zgłoszone Agencji już w listopadzie 2003[96].

4 lutego 2006, 35 członków Rady Nadzorczej IAEA stosunkiem głosów 27-3 (przy pięciu głosach wstrzymujących się – Algieria, Białoruś, Indonezja, Libia i RPA) przegłosowała zgłoszenie kwestii rozwoju programu nuklearnego w Iranie Radzie Bezpieczeństwa ONZ. Działanie IAEA było zasugerowane przez Wielką Brytanię, Francję i Niemcy, z poparciem Stanów Zjednoczonych. Dwaj stali członkowie Rady, Rosja i Chiny, zgodziły się na przekazanie kwestii Radzie Bezpieczeństwa tylko pod warunkiem niepodjęcia przez IAEA żadnych działań do marca 2006. Trzej członkowie Rady głosujący przeciwko działaniu IAEA to Wenezuela, Syria i Kuba[97][98]. W odpowiedzi na decyzję Rady, 6 lutego Iran zawiesił wprowadzone dobrowolnie ustalenia protokołów dodatkowych, jak też pozostałe dobrowolne niewiążące prawnie aspekty współpracy z IAEA wykraczające poza umowę[99]/

Pod koniec lutego 2006, dyrektor IAEA Mohammad El-Baradei wystąpił z sugestią układu, w myśl którego Iran miałby zaprzestać wzbogacania uranu na skalę przemysłową, ograniczając swoje działania do jednego zakładu malej skali o charakterze pilotażowym, godząc się równocześnie na import paliwa nuklearnego z Rosji. Irańczycy zadeklarowali, że w zasadzie nie są skłonni do zaprzestania wzbogacania uranu, lecz mogą rozważyć rozwiązania kompromisowe[100]. W marcu 2006 administracja George W. Busha jasno dała do zrozumienia, że nie zamierza akceptować jakichkolwiek prac nad wzbogacaniem uranu prowadzonych przez władze irańskie[101].

Rada Naczelna IAEA odwlekała oficjalne zgłoszenie działań irańskich Radzie Bezpieczeństwa ONZ – tego typu raport wymagany jest w myśl ustaleń artykułu XII.C statutu IAEA[102] – do 27 lutego 2006[103]. Rada zwykle podejmuje decyzje konsensusem, lecz w tym przypadku, co jest rozwiązaniem rzadkim, decyzję przyjęto przez głosowanie, przy 12 głosach wstrzymujących się[104][105].

11 kwietnia 2006, prezydent Iranu Mahmud Ahmadineżad ogłosił, że jego kraj dokonał udanej próby wzbogacenia uranu. Oświadczenie wygłoszone w mieście Meszhed i transmitowane przez telewizję zawierało następujące stwierdzenie prezydenta: „Oficjalnie ogłaszam, że Iran dołączył do grupy państw, które są w posiadaniu technologii jądrowej”. Uran wzbogacono do poziomu 3,5% za pomocą ponad stu centryfug.

13 kwietnia 2006, po oświadczeniu sekretarz stanu USA Condoleezzy Rice z 12 kwietnia, mówiącym o konieczności podjęcia przez Radę bezpieczeństwa ONZ „ostrych kroków” w celu nakłonienia Teheranu do zmiany kierunku swoich ambicji nuklearnych, prezydent Ahmadineżad oświadczył, że Iran nie wycofa się ze wzbogacania uranu i że świat musi uznać Iran za potęgę nuklearną: „Naszą odpowiedzą w kierunku tych, którzy źli są na uzyskanie przez Iran pełnego cyklu przetwarzania paliwa nuklearnego jest: bądźcie źli i z tej złości pomrzyjcie”, gdyż „nie będziemy prowadzić z kimkolwiek rozmów o prawach narodu irańskiego do wzbogacania uranu[106]„.

14 kwietnia 2006 Institute for Science and International Security opublikował serię poddanych analizie zdjęć satelitarnych irańskich zakładów nuklearnych w miastach Natanz i Esfaham[107]. Na zdjęciach widoczne jest nowe wejście do tunelu niedaleko zakładu wzbogacania uranu w Esfahan i prace konstrukcyjne nad zakładem wzbogacania uranu w Natanz. Dodatkowo, szereg zdjęć wykonanych od roku 2002 przedstawia podziemne instalacje wzbogacania uranu i ich stopniowe pokrywanie ziemią, betonem i innymi materiałami. Obydwa zakłady stanowiły już obiekt inspekcji ekspertów z IAEA i przedmiot porozumienia z Agencją.

Iran na żądania zaprzestania wzbogacania uranu odpowiedział 24 sierpnia 2006, wyrażajać chęć powrotu do negocjacji, lecz odmawiając zaprzestania prac[108].

Qolam Ali Hadad-adel, członek parlamentu irańskiego, 30 sierpnia 2006 powiedział, że Iran miał prawo do „pokojowego zastosowania procesu wzbogacania uranu, zaś wszyscy urzędnicy państwowi zgadzają się z tą decyzją”, jak podała półoficjalna irańska studencka agencja prasowa. „Iran otworzył Europie drzwi do negocjacji i ma nadzieje, że odpowiedź na ich propozycję pakietu ugodowego sprowadzi ich do stołu rozmów”[108].

Rezolucją 1696 z 31 lipca 2006, Rada Bezpieczeństwa ONZ zażądała od Iranu zaprzestania prac nad wzbogacaniem i przetwarzaniem uranu[109].

Rezolucja Rady Bezpieczeństwa ONZ 1737 z 26 grudnia 2006 nałożyła na Iran szereg sankcji za niezgodność działań z wcześniejszą rezolucją, wzywającą Teheran do natychmiastowego zaprzestania wzbogacania uranu[110]. Sankcje były przede wszystkim wymierzone w transfer technologii nuklearnych i balistycznych[111] i, w odpowiedzi na zastrzeżenia zgłoszone przez Rosję i Chiny, łagodniejsze niż oczekiwane ze strony Stanów Zjednoczonych[112]. Rezolucja została podjęta po ogłoszeniu przez IAEA faktu dopuszczenia inspektorów do instalacji nuklearnych w myśl układu z IAEA z jednoczesnym niezaprzestaniem działań związanych ze wzbogacaniem uranu[113].

Działania europejskie 2002–2006[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Około roku 2005 Niemcy odmówiły wyeksportowania do Iranu jakichkolwiek urządzeń związanych z technologią nuklearną lub zwrócenia wpłaconych przez Iran środków na zakup takich urządzeń w latach 80. XX wieku[53].

Od roku 2007[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Rada Bezpieczeństwa Organizacji Narodów Zjednoczonych[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Rada Bezpieczeństwa ONZ podjęła sześć rezolucji dotyczących Iranu.

Rezolucją 1696 z 31 lipca 2006 Rada Bezpieczeństwa zażądała od Iranu zawieszenia działań związanych e wzbogacaniem uranu, przywołując rozdział 7 Karty Narodów Zjednoczonych, by żądanie było w stosunku do Iranu prawnie wiążące.

Rezolucja Rady Bezpieczeństwa ONZ 1737 z 23 grudnia 2006 nakładał na Iran sankcje po tym, jak rząd w Teheranie odmówił zaniechania rozwoju techniki nuklearnej. Rezolucja wzywała Iran do zaprzestania współpracy z krajami trzecimi, podjęcia współpracy z IAEA i areszt mienia szeregu osób i organizacji powiązanych z irańskim programem nuklearnym i zbrojeniowym. Rezolucja powołała również komisję mającą monitorować wprowadzenie sankcji[114].

24 marca 2007 Rada podjęła decyzję o rozszerzeniu zakresu sankcji[115], przyjmując rezolucję 1747, rozszerzającą listę poddanych sankcjom osób i instytucji. Przyjęto też sugestię pięciu stałych członków Rady oraz Niemiec o rozwiązaniu kwestii irańskiego programu nuklearnego.

Wydając rezolucję 1803 z 3 marca 2008, Rada Bezpieczeństwa zadecydowała o rozszerzeniu sankcji na dodatkową grupę instytucji finansowych, ograniczyć przejazdy dodatkowej grupy osób i zakazać eksportowania do Iranu produktów podwójnego wykorzystania, związanych z technologią nuklearną i rakietową[116]. Wprowadzenie sankcji monitorowane jest przez komitet Rady Bezpieczeństwa[117].

Rada Bezpieczeństwa ONZ przyjęła 27 września 2008 rezolucję 1835, potwierdzającą ustalenia czterech poprzednich dokumentów. Jako jedyna z sześciu przytoczonych tu rezolucji, nie przywoływała ona Karty Narodów Zjednoczonych i jej rozdziału 7.

9 czerwca 2010 ONZ uchwaliła rezolucję 1929, nakładającą całkowite embargo zbrojeniowe na Iran, wprowadzającą ograniczenia przejazdów dla określonych przedstawicieli organów władzy, odsuwającą Iran od jakichkolwiek działań związanych z rakietami balistycznymi, zamrażającą środki Armii Strażników Rewolucji Islamskiej oraz Irańskich Linii transportowych, jak też nakładającą obowiązek prowadzenia inspekcji wszystkich irańskich towarów i intytulacji finansowych, na przykład banków, na terytorium działania. Turcja i Brazylia były przeciwko przyjęciu rezolucji, zaś Liban wstrzymał się od głosu; rezolucja została uchwalona stosunkiem głosów 12 do 2. Niektóre kraje, w tym Stany Zjednoczone, państwa Unii Europejskiej, Australia[118], Kanada[119], Japonia[120], Norwegia[121], Korea Południowa[122] i Rosja[123] wprowadziły i zaostrzyły powyższe sankcje.

Międzynarodowa Agencja Energii Atomowej[edytuj | edytuj kod]

W lutym 2001 anonimowi dyplomaci IAEA stwierdzili, że większość uzyskiwanych przez służby wywiadowcze Stanów Zjednoczonych informacji wywiadowczych które przekazano IAEA była niewiarygodna, jak też, że żadna z uzyskanych informacji nie doprowadziła do znaczących odkryć na terenie Iranu[124].

10 maja 2007 zarówno Iran jak i IAEA ostro zaprzeczyły doniesieniom o zatrzymaniu przez Iran ekspertów IAEA próbujących uzyskać dostęp do irańskich zakładów wzbogacania uranu. 11 marca 2007 agencja Reuters zamieściła wypowiedź rzecznika Międzynarodowej Agencji Energii Atomowej Marca Vidricaire, ktory stwierdził: „Nigdy, włączywszy w to kilka ostatnich tygodni, nie odmówiono nam dostępu do zakładów wzbogacania uranu. Zwykle nie komentujemy tego typu doniesień, lecz tym razem czujemy, ze kwestię należy wyjaśnić (...) Gdybyśmy stanęli w obliczu takiego problemu, musielibyśmy to zgłosić Radzie [w której zasiada 35 państw] (...) Nie stało się tak, gdyż wspomniane domniemane wydarzenie nie miało miejsca”[125].

30 lipca 2007 inspektorzy IAEA odbyli pięciogodzinna wizytę w kompleksie Arak – pierwszą tego typu wizytę od kwietnia. W dalszych dniach planowano inspekcje kolejnych zakładów. W kontekście tych wizyt padły sugestie, jakoby dostęp do zakładów związanych z techniką atomową miał być udzielony w celu uniknięcia przyszłych sankcji[126].

Pod koniec października 2007, jak podał dziennik International Herald Tribune, przewodniczący IAEA Mohamed ElBaradei stwierdził, że nie widział dowodów na rozwijanie broni jądrowej przez Iran. Dziennik zacytował następujące słowa ElBaradeia: „Wiedzieliśmy, że w Iranie mogą być prowadzone badania nad potencjalnym uzbrojeniem. Dlatego też zdecydowaliśmy o niedawaniu Teheranowi wolnej ręki, gdyż stanęliśmy w obliczu wielu pytań bez odpowiedzi (...) Czy jednak zobaczyliśmy materiały radioaktywne, które można w każdej chwili wykorzystać do zbudowania bomby? Nie. Czy zobaczyliśmy faktycznie program zbrojeniowy? Nie.” International Herald Tribune napisał również: „ElBaradei stwierdził, że martwi się rosnącą siłą retoryki Stanów Zjednoczonych, która w jego rozumieniu koncentruje się na domniemanych intencjach stworzenia przez Iran broni nuklearnej, nie zaś na dowodach, że Teheran faktycznie się zbroi. Gdyby istniały twarde dowody, ElBaradei wyraził chęć ich zobaczenia.”[127]

Izrael skrytykował raporty IAEA dotyczące Iranu, jak też byłego przewodniczącego Agencji, Mohameda ElBaradeia. Izraelski Minister of Strategic Affairs Avigdor Lieberman odrzucił raporty agencji atomowych ONZ jako nieakceptowalne i oskarżył przewodniczącego IAEA ElBaradeia i działania proirańskie[128].

W wywiadzie udzielonym w lutym 2009, przewodniczący IAEA Mohamed ElBaradei stwierdził, że Iran jest w posiadaniu niskowzbogaconego uranu, „nie oznacza to jednak, że jutro będą dysponować bronią nuklearną, gdyż tak długo, jak są pod nadzorem IAEA i tak długo, jak nie podejmują działań zbrojeniowych, wszystko wiadomo.” ElBaradei stwierdził też deficyt wiary w Iran, lecz uznał, ze nie wolno go rozdmuchiwać i że „wiele innych państw wzbogaca uran bez narzekań reszty świata.”[129]

IAEA w dalszym stopniu nie była w stanie wysnuć wniosków na temat ewentualności prowadzenia przez władze irańskie tajnego programu zbrojeniowego. Zwykle wysnuwa ona wnioski o braku niezadeklarowanych działańnuklearnych tylko w przypadku państw, które stosują się do Protokołu dodatkowego. Iran zatrzymał swoje dobrowolne u niewiążące prawnie wprowadzenie Protokołu dodatkowego oraz wszelką współpracę dobrowolną z IAEA, która nie wynikałaby z układu zabezpieczającego po tym, jak IAEA zadecydowała o przedstawieniu wykazywanych przez Iran niezgodności Radzie Bezpieczeństwa ONZ w lutym 2006[99]. Skutkiem tego było przyjęcie przez Radę bezpieczeństwa ONZ rezolucji 1737, przywołującej rozdział 7 Karty Narodów Zjednoczonych, która obligowała Iran do wprowadzenia Protokołu dodatkowego. Iran utrzymywał, że zaangażowanie Rady Bezpieczeństwa ONZ w „kwestię pokojowych działań nuklearnych Islamskiej Republiki Iranu” jest nieprawne i złośliwe[130]. W oświadczeniu o zabezpieczeniach z roku 2007 IAEA nie dopatrzyła się niezadeklarowanych materiałów radioaktywnych ani działań jądrowych w 47 z 82 krajów, które ratyfikowały zarówno układ o nierozprzestrzenianiu broni jądrowej jak i Protokoły dodatkowe, choć podobnych wniosków nie dało się wysnuć w przypadku pozostałych 25 krajów[131]. W sierpniu 2007 Iran i IAEA podpisały porozumienie poszukujące rozwiązania otwartych kwestii[132], dokonując postępu w rozwiązaniu niektórych kwestii otwartych, oprócz „domniemanych badań” nad irańską bronią jądrową[133]. Iran twierdzi, ze nie odniósł się do domniemanych badań w planie prac IAEA, gdyż ta kwestia nie została w nim uwzględniona[134]. IAEA nie odkryła faktycznego wykorzystywania materiałów rozszczepialnych w związku z domniemanymi badaniami i twierdzi, że z ubolewaniem nie jest w stanie przedstawić Iranowi kopii dokumentów z nimi związanych, lecz zapewnia, ze dokumentacja jest wyczerpująca i szczegółowa w stopniu, który wymusza poważne jej potraktowanie. Iran z kolei twierdzi, że przypuszczenia są oparte na „sfałszowanych” dokumentach i „sfabrykowanych” danych i że nie otrzymał kopii dokumentów, które pozwoliłyby mu się dowieść ich sfałszowania i fabrykacji[135][136].

W lutym 2009 dyrektor generalny IAEA stwierdził w wywiadzie dla Radio France, że wierzy, iż wykluczono możliwość ataku wojskowego na instalacje nuklearne w Iranie. „Siły wolno użyć wyłącznie w ostateczności (...) po wyczerpaniu wszystkich możliwości działań politycznych.”[137][138];. Były dyrektor generalny IAEA Hans Blix skrytykował rządy państw Zachodu za lata stracone w wyniku „nieefektywnego podejścia” do tematyki irańskiego programu nuklearnego. Blix zasugerował, by państwa Zachodu zaproponowały „gwarancję przed atakami z zewnątrz i działalnością przewrotową wewnątrz” sugerując również, że zaangażowanie w dyplomatykę regionalną ze strony Stanów Zjednoczonych „stałoby się dla Iranu lepszą motywacją do osiągnięcia porozumienia w kwestiach nuklearnych niż oświadczenia Busha o tym, że Iran musi się zachowywać.”[139];

W lipcu 2009 Yukiya Amano, świeżo mianowany przewodniczący IAEA powiedział, że „nie widzi w oficjalnych dokumentach IAEA dowodu” na to, by Iran próbował zyskać możliwość rozwijania broni nuklearnej[140].

We wrześniu 2009 dyrektor generalny IAEA Mohamed El Baradei stwierdził, ze Iran złamał prawo, nie ujawniając wcześniej faktu posiadania drugiego zakładu wzbogacania uranu, zlokalizowanego w miejscowości --Kom (miasto)|Kom]]. Mimo tego, jak stwierdził El Baradei, Organizacja Narodów Zjednoczonych nie dysponowała wystarczającymi dowodami na to, by w Iranie rozwijano program badań nuklearnych[141].

W listopadzie tego samego roku składająca się z przedstawicieli 35 państw Rada Naczelna Międzynarodowej Agencji Energii Atomowej przytłaczającą większością poparła żądanie Stanów Zjednoczonych, Rosji, Chin i trzech innych mocarstw, by Iran natychmiast zaprzestał budowania swojego nowo ujawnionego zakładu nuklearnego i by zatrzymał proces wzbogacania uranu. Przedstawiciele Iranu zignorowali przyjęcie tej rezolucji głosami 25 członków Rady, lecz Stany Zjednoczone wraz z państwami popierającymi ich politykę dały do zrozumienia, ze w przypadku da;dalszego oporu ze strony władz w Teheranie, ONZ może na Iran nałożyć kolejne sankcje[142].

W lutym 2010 IAEA wydała raport krytykujący Iran za niewyjaśnienie szczegółów zakupu wrażliwej technologii oraz przeprowadzenie testów detonatorów wysokiej precyzji oraz głowic pocisków zmodyfikowanych tak, by mogły przenosić większe ładunki. Tego typu eksperymenty łączą się bezpośrednio z kwestią głowic atomowych[143].

W maju 2010 IAEA wydała raport, w którym zawarto wzmiankę o zadeklarowaniu przez Iran produkcji 2,5 tony niskowzbogaconego uranu; taka ilość po wzbogaceniu do wyższej wartości mogłaby posłużyć do skonstruowania dwóch głowic nuklearnych. Iran w myśl raportu odmówił udzielenia odpowiedzi na szereg pytań dotyczących prowadzonych działań, w tym działań określonych przez Agencję jako posiadające „potencjalny wymiar zbrojeniowy”[144][145].

Iran odmówił inspektorom IAEA wjazdu na teren kraju w lipcu 2010. Agencja odrzuciła podane przez Iran powody zakazu wjazdu swoich inspektorów i wyraziła pełne poparcie ich działań. Iran oskarżył wspomnianych inspektorów o nieprawidłowe raportowanie faktu zaginięcia pewnych urządzeń.[146].

IAEA oświadczyła w sierpniu 2010, że Iran rozpoczął wykorzystywanie drugiego zestawu 164 centryfug połączonych w kaskadę w celu wzbogacenia uranu do poziomu 20% w pilitażowych zakładach w Natanz[147].

Iran[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Wywiady i sondaże sugerują, że większość obywateli Iranu popiera dążenia nuklearne swojego kraju[148][149][150]. Badania opinii publicznej z roku 2008 pokazują, że większość obywateli Iranu chce opracowania w ich państwie technologii związanych z energetyką jądrową, zaś 90% uważa za kwestię ważną (81% za bardzo ważną), by Iran posiadł wiedzę o pełnym cyklu paliwowym[151]. Choć Irańczycy nie są Arabami, społeczności sześciu krajów arabskich również uważają, Iran ma prawo do rozwijania własnego programu badań nad technologią nuklearną i że nie powinno się na Iranie wywierać presji celem zakończenia rozwoju owego programu[152]. Badanie opinii publicznej przeprowadzone we wrześniu 2010 przez International Peace Institute ujawniło, że 71 procent Irańczyków popiera rozwój broni nuklearnej, co stanowi znaczny wzrost w stosunku do wyników poprzednich badań prowadzonych przez tę samą agencję[153].

Wyjaśniając, dlaczego program wzbogacania uranu nie został zadeklarowany Międzynarodowej Agencji Energii Atomowej, Iran argumentował, że przez poprzednie 24 lata „byliśmy przedmiotem szeregu najcięższych sankcji i ograniczeń związanych z materiałami i technologią związaną z pokojowymi badaniami nad energią atomową”, skutkiem czego część programu prowadzona była w sposób tajny. Iran stwierdził, że intencją Stanów Zjednoczonych jest „wyłączniie pozbawienie Iranu” niezbywalnych praw do wzbogacania pierwiastków rozszczepialnych „ raz na zawsze”, jak też, ze Stany Zjednoczone pozostają głuche na działania nuklearne i zbrojeniowe prowadzone przez Izrael[154]. Irna rozpoczął badania nad technologią nuklearną już w roku 1975, gdy Francja podjęła współpracę z rządem w Teheranie, uruchamiając centrum Esfahan Nuclear Technology Center (ENTC) mające służyć szkoleniu personelu, który pracowac miał przy opracowywaniu określonych faz cyklu paliwowego[155][156]. Iran nie ukrywał pozostałych elementów swojego programu nuklearnego. Dla przykładu, wydobywanie i przetwarzanie uranu zostało ujawnione w ogólnokrajowej stacji radiowej[157][158], władze stwierdziły też, że w trakcie konsultacji z Agencją Energii Atomowej i jej krajami członkowskimi w latach 90. XX wieku podkreślały plany zdobycia w celach wyłącznie pokojowych technologii wzbogacania pierwiastków promieniotwórczych[154]. IAEA wiedziała również o kontraktach zawartych z państwami trzecimi na dostawę technologii nuklearnej, lecz wsparcie dla tych umów ustało po „ocenie specjalnych narodowych sił wywiadowczych USA stwierdzającej, że choć często opisywane w mediach intencje nuklearne Iranu znajdują sie całkowicie w fazie planowania, ambicje Szacha mogą doprowadzić do tego, że Iran zacznie rozwijać arsenał nuklearny, szczególnie po udanych testach nuklearnych przeprowadzonych przez Indie w maju 1974.”[159]. W roku 2003 IAEA ogłosiła, ze Iran nie dopełnił swoich zobowiązań, które obligowały państwo do zgłoszenia części operacji wzbogacania pierwiastków rozszczepialnych; według Iranu operacja ta rozpoczęła się w roku 1985, zaś obowiązek oznajmienia o tym fakcie przed IAEA wynikał z podpisanej umowy o ograniczaniu działań nuklearnych. IAEA dodatkowo ogłosiła, że Iran zgodził się na ujawnienie wymaganych przez Agencję informacji i „przyjąć politykę współpracy oraz pełnej przejrzystości” działań korygujących[81].

Rząd Iranu kilkakrotnie oferował kompromisowe rozwiązania, w myśl których można było nałożyć ścisłe ograniczenia na te z elementów prowadzonego w kraju programu nuklearnego, które wykraczały poza zobowiązania wynikające z układu o nierozprzestrzenianiu broni jądrowej wraz z protokołami dodatkowymi tak, by zapewnić, ze program nie zostanie potajemnie przekształcony na produkcję broni[160]. Oferty zawierały między innymi obietnicę prowadzenia irańskiego programu badań technologii nuklearnych w ramach międzynarodowego konsorcjum przy pełnym współudziale rządów państw trzecich. Propozycja ta odpowiadała rozwiązaniu przedstawionemu przez komitet ekspercki IAEA, badający ryzyko transferu pokojowej technologii nuklearnej do celów wojskowych[18]. Iran proponował również zaniechanie wykorzystywania technologii ekstrakcji plutonu, co miałoby zapewnić, że reaktor jądrowy w mieście Arak nie bedzie wykorzystany do produkcji bomb[161]. W czasie późniejszym podawano, ze Irańczycy zadeklarowali również korzystanie z centryfug, które ulegałyby autodestrukcji podczas próby wykorzystania ich do wzbogacania uranu ponad współczynnik niezbędny do zastosowań cywilnych[162]. Mimo jednak wystosowywania przez pięciu członków stałych Rady Bezpieczeństwa ONZ i Niemiec ofert współpracy na polu technologii nuklearnych, Iran odrzucił żądanie Rady o zaprzestanie dalszego rozwijania programu atomowego[163]. Przedstawiciel Iranu zapewniał wtedy, że zajęcie się tą kwestią było ze strony Rady Bezpieczeństwa bezzasadne, pozbawione podstaw prawnych i użyteczności praktycznej, gdyż prowadzony w kraju pokojowy rozwój technologii atomowej nie stanowi zagrożenia dla bezpieczeństwa i pokoju światowego i że tego typu działania są sprzeczne z punktem widzenia większości krajów wchodzących w skład ONZ, które Rada ma za zadanie reprezentować.

„Powinni wiedzieć, że naród irański nie ugnie się pod naciskami i nie pozwoli na deptanie swoich praw” powiedział 31 sierpnia 2006 prezydent Iranu Mahmoud Ahmadinejad; jego przemówienie przed tłumem w północnoirańskim mieście Urmia transmitowała telewizja. Przed swoimi najbardziej zagorzałymi zwolennikami w leżącej na uboczu elektrowni irański przywódca zaatakował fenomen „zastraszania” ze strony ONZ, według niego kierowany przez Stany Zjednoczone. Ahmadinejad skrytykował odrzucenie przez Biały Dom jego oferty transmitowanej przez telewizję debaty z prezydentem Bushem. „Mówią, ze wspierają dialog i wolny przepływ informacji&rdquo, powiedział Ahmadinejad. „Lecz gdy dostali propozycję debaty, unikali jej i ją odrzucili.” Powiedział też, że sankcje nie są w stanie odwieść Irańczyków od podjętej decyzji o podjęciu ścieżki postępu. Jak podała będąca pod wpływem rządu irańska agencja informacyjna IRNA, „wręcz przeciwnie – wiele z naszych sukcesów, w tym uzyskanie dostępu do technologii nuklearnych i produkcja ciężkiej wody osiągnięto mimo sankcji.”

Iran podkreśla pokojowy charakter prowadzonego wzbogacania uranu, lecz wiele z krajów Zachodu, w tym Stany Zjednoczone, twierdzi, że Iran dąży do wyprodukowania broni jądrowej lub do uzyskania samej możliwości takiego działania. Termin 31 sierpnia, wyznaczony w rezolucji nr 1696 Rady Bezpieczeństwa ONZ, wzywał Iran do zawieszenia działań związanych ze wzbogacaniem pierwiastków radioaktywnych lub pogodzenia się z możliwością zastosowania sankcji gospodarczych. Stany Zjednoczone były przekonane, ze Rada Bezpieczeństwa nałoży na Iran sankcje po zebraniu ministrów wysokiego szczebla w połowie września. Podsekretarz stanu rządu amerykańskiego Nicholas Burns powiedział: „będziemy pracować w kierunku wprowadzenia sankcji w sposób energiczny i z poświęceniem, gdyż takich działań nie wolno pozostawić bez odpowiedzi (...) Irańczycy w sposób jednoznaczny pracują dalej nad technologią jądrową; podejmują działania, których podjęcia nie chce od nich Międzynarodowa Agencja Energii Atomowej, nie chce też ich Rada Bezpieczeństwa ONZ. Musi nastąpić w tej kwestii międzynarodowa odpowiedź i wierzymy, zę tak się stanie.”[108]

Władze Iranu zapewniają, ze nie ma podstaw prawnych do przekazania sprawy Radzie Bezpieczeństwa ONZ, gdyż IAEA nie udowodniła, by uprzednio nieujawnione jej działania miały związek z programem zbrojeniowym i że całość materiałów rozszczepialnych (w tym uprzednio nieujawnionych) znajdujących się na terenie kraju ma znany status i nie została przekazana na cele wojskowe. Artykuł XII.C statutu IAEA[164] wymaga przekazania Radzie Bezpieczeństwa ONZ każdego przypadku niezgodności działań kraju z przyjętymi zasadami[165]. Rada Naczelna IAEA w rzadkiej niepolegającej na konsensusie decyzji przy dwunastu głosach wstrzymujących się[104] zadecydowała, że „ wielokrotne niedopatrzenia Iranu i łamanie przezeń obowiązków wynikających z układu o nierozprzestrzenianiu broni jądrowej” jak podała Międzynarodowa Agencja Energii Atomowej w listopadzie 2003 stanowi niezgodność z artykułem XII.C statutu IAEA[96].

Iran minimalizuje również niemożność IAEA do zweryfikowania wyłącznie pokojowej natury programu własnych badań nuklearnych, argumentując, że IAEA wysnuła takie wnioski wyłącznie w grupie państw, które podpisały i ratyfikowały Protokół dodatkowy. IAEA była w stanie stwierdzić, że zadeklarowany przez Iran materiał radioaktywny nie był przekazany do celów innych niż cywilne[166], nie była jednak w stanie stwierdzić braku niezadeklarowanych w Agencji działań. Jak stwierdził raport IAEA z roku 2007, wśród 82 państw, które ratyfikowały układ o nierozprzestrzenianiu broni jądrowej i Protokół dodatkowy w 47 przypadkach nie znaleziono śladów niezadeklarowanych Agencji działań nuklearnych, zaś w 35 przypadkach zaistniały podejrzenia o prowadzenie niezgłoszonych IAEA prac[167]. Iran zatrzymał wprowadzanie w życie ustaleń Protokołu dodatkowego i wszelką współpracę z IAEA nie wymuszoną przez podpisane zobowiązania po tym, jak Rada Nadzorcza IAEA zdecydowała w lutym 2006 powiadomić o niezgodnościach Radę Bezpieczeństwa ONZ[99]. Iarn nalegał, ze tego typu współpraca była dobrowolna, lecz 26 grudnia 2006 Rada Bezpieczeństwa ONZ przyjęła rezolucję 1737[168], przywołując w niej rozdział VII Karty Narodów Zjednoczonych, co między innymi wymusiło na Iranie podjęcie pełnej współpracy z IAEA, „ponad formalnymi wymogami stawianymi przez układ zabezpieczający oraz Protokół dodatkowy”. 19 listopada 2008 IAEA podała, że „będąc w stanie nadal twierdzić, że w Iranie nie doszło do przekazania materiału nuklearnego do celów wojskowych, (...) nie jest jednak w stanie poczynić znacznych kroków (...) w pozostałych kluczowych kwestiach (...) z uwagi na brak współpracy ze strony Iranu„[169]. Iran utrzymywał, że zaangażowanie Rady Bezpieczeństwa w „kwestię pokojowych działań nuklearnych Islamskiej Republiki Iranu” jest bezprawne i ma złośliwy charakter[170]. Iran argumentował również, że rezolucja Rady Bezpieczeństwa ONZ wzywająca kraj do zaprzestania wzbogacania uranu stanowiła naruszenie ustaleń artykułu IV Ukłądu o nierozprzestrzenianiu broni jądrowej, w którym uznaje się niezbywalne prawa sygnatariuszy układu do posiadania technologii nuklearnej dla celów pokojowych[171][172].

Iran zgodził się na wprowadzenie Protokołu dodatkowego na warunkach układu z roku 2003 podpisanego w Teheranie i układu podpisanego w Paryżu w roku 2004 i utrzymywał w mocy ustalenia tych umów przez dwa lata przed wycofaniem się z ustaleń układu paryskiego, co nastąpiło w roku 2006, po załamaniu się negocjacji z Trójką UE. Od tego czasu Iran deklarował nie tylko chęć wprowadzenia w życie Protokołu dodatkowego, lecz również wprowadzenie zasad przejrzystości prowadzonego programu, przekraczające wymogi Protokołu dodatkowego, o ile uznane zostanie jego prawo do prowadzenia pokojowego programu nuklearnego. Rada Bezpieczeństwa ONZ nalegała jednak na całkowite zatrzymanie wzbogacania i przetwarzania uranu, zaś ONZ jednoznacznie wykluczyła możliwość zezwolenia Iranowi na produkcję własnego paliwa nuklearnego, nawet przy dokładnych inspekcjach ze strony organów międzynarodowych[173].

9 kwietnia 2007 Iran ogłosił rozpoczęcie wzbogacania uranu z wykorzystaniem 3000 wirówek, najprawdopodobniej w zakładach w Nathanz. „Wielkim zaszczytem jest, że mogę dziś ogłosić, iż nasze drogie państwo dołączyło do grupy narodów z potencjałem nuklearnym i że może na skalę przemysłową produkować paliwo nuklearne” powiedział Ahmadinejad.[174].

22 kwietnia 2007 rzecznik irańskiego Ministerstwa Spraw Zagranicznych Mohammad Ali Hosseini ogłosił, że Iran nie zamierza zawieszać wzbogacania pierwiastków radioaktywnych przed rozmowami z [[Wysoki przedstawiciel Unii do spraw zagranicznych i polityki bezpieczeństwa wysokim przedstawicielem Unii do spraw zagranicznych i polityki bezpieczeństwa [[Javierem Solaną, mającymi odbyć się 25 kwietnia 2007[175].

W marcu 2009 Iran ogłosił plany otwarcia instalacji w Buszehr dla turystów, co miało podkreślić pokojowy charakter prowadzonych prac[176]

W reakcji na rezolucję IAEA z listopada 2009 wzywającej do natychmiastowego zaprzestania prac nad budową nowo zgłoszonej instalacji nuklearnej oraz zatrzymanie wzbogacania uranu, rzecznik prasowy irańskiego MSZ Ramin Mehmanparast przyrównał rewolucję do „pokazu (...) mającego na celu wywarcie na Iran presji, co będzie bezskuteczne”[142]. Rząd Iranu udzielił po tym fakcie pozwolenia krajowej organizacji atomowej do rozpoczęcia budowy kolejnych dziesięciu zakładów, rozszerzając tmy samym możliwości energetyczne kraju[177].

Prezydent Iranu Mahmoud Ahmadinejad 1 grudnia 2009 skrytykował groźby sankcji ze strony ONZ o ile Iran nie przyjmie proponowanej przez ONZ wersji programu nuklearnego, twierdząc, że tego typu posunięcia ze strony państw Zachodu nie powstrzymają działań irańskich. Ahmadinejad powiedział krajowej stacji telewizyjnej, że wierzył, iż dalsze negocjacje pomiędzy jego krajem a mocarstwami światowymi w kwestiach nuklearnych nie będą potrzebne, opisując groźby Zachodu o odizolowaniu Iranu jako „niedorzeczne”[177].

Pod obserwacją wysokich ranga przedstawicieli Iranu i Rosji 21 sierpnia 2010 rozpoczęto wprowadzanie paliwa nuklearnego do instalacji Buszehr II. Jak podały media państwowe, było to działanie w kierunku zapewnienia dostaw prądu elektrycznego wytwarzanego z paliw rozszczepialnych. Media państwowe podawały, ze reaktor rozpocznie wytwarzanie prądu w ciągu dwóch miesięcy, lecz rosyjska agencja atomowa podała czas dłuższy. Ajatollah Ali Khamenei, przywódca państwa, potwierdził w sierpniu 2010 prawo swojego kraju do uruchamiania elektrowni atomowych[178].

Stany Zjednoczone[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Prezydent George W. Bush 31 sierpnia 2006 stwierdził, że „należy wyciągnąć konsekwencje” wobec irańskiego oporu przed żądaniami zaprzestania wzbogacania uranu. Dodał, zę „świat stoi w obliczu poważnego zagrożenia ze strony radykalnego irańskiego reżimu. Reżim ten zbroi i finansuje organizację Hezbollah, jak też jej doradza.”[179] IAEA wydała w tym czasie raport stwierdzający, że Iran nie zaprzestał wzbogacania uranu, co potwierdził przedstawiciel rządu brytyjskiego. Raport otworzył możliwość nałożenia na Iran sankcji ze strony Rady Bezpieczeństwa ONZ. Stojąc przed naciskami czasowymi ze strony ONZ i żądaniami zaprzestania wzbogacania pierwiastków radioaktywnych, Iran nie pozostawiał wątpliwości co do tego, że nie spełni oczekiwań Zachodu i że będzie kontynuował program nuklearny[108].

Raport amerykańskiego Kongresu z 23 sierpnia 2006 podsumował udokumentowaną historię irańskiego programu nuklearnego, poczynił jednak również pewne spostrzeżenia pod katem IAEA. Agencja odpowiedziała zawierającym ostre sformułowania listem do ówczesnego przewodniczącego kongresowej komisji wywiadowczej Petera Hoekstra, w którym tezy, jakoby inspektor IAEA został zwolniony po naruszeniu zasad Agencji nakazujących „mówienie całej prawdy ” na temat Iranu za „skandaliczne i nieuczciwe” i wskazującym inne błędy rzeczowe, takie jak stwierdzenie, jakoby Iran dopuszczał się wzbogacania uranu do poziomu właściwego do zastosowań wojskowych[180].

John Bolton, ówczesny ambasador USA przy ONZ, stwierdził 31 sierpnia 2006, że oczekiwał natychmiastowego wprowadzenia sankcji po upłynięciu ultimatum, zapowiadając spotkania wysokich urzędników państwowych w najbliższych dniach, po których nastąpić miały negocjacje w kwestii języka, w którym miała powstać rezolucja nakładająca sankcje. Bolton stwierdził, zę po upłynięciu ultimatum „w górę pójdzie niewielka flaga. (...) w kwestiach tego, co stanie się później, jeśli Iran nie zaprzestania wzbogacania uranu, staną w niezgodności z rezolucją. W tym momencie podejmiemy dyskusję na temat tego, jak wprowadzić środki uzgodnione pomiędzy ministrami spraw zagranicznych.” Pięciu stałych członków Rady Bezpieczeństwa ONZ zaoferowało wraz z Niemcami pakiet rozwiązań mających nakłonić Iran do ponownego przystąpienia do negocjacji, Iran jednak odmówił uprzedniego zaniechania prac nad technologią nuklearną. Proponowany pakiet zawierał oferty poprawiające dostęp Iranu do zdobyczy gospodarki międzynarodowej poprzez uczestnictwo w takich strukturach, jak [{WTO]] i modernizację infrastruktury telekomunikacyjnej kraju. W trakcie negocjacji podejmowano również temat zniesienia ograniczeń na eksport cywilnych samolotów produkcji amerykańskiej i europejskiej do Iranu, jak też propozycję „świeżego startu” w negocjacjach"[108].

Przedstawiciele IAEA w roku 2007

*IAEA officials complained in 2007 that most U.S. intelligence shared with it to date about Iran's nuclear program proved to be inaccurate, and that none had led to significant discoveries inside Iran through that time.[181]

- Through 2008, the United States repeatedly refused to rule out using nuclear weapons in an attack on Iran. The U.S. Nuclear Posture Review made public in 2002 specifically envisioned the use of nuclear weapons on a first strike basis, even against non-nuclear armed states.[182] Investigative reporter Seymour Hersh reported that, according to military officials, the Bush administration had plans for the use of nuclear weapons against "underground Iranian nuclear facilities".[183] When specifically questioned about the potential use of nuclear weapons against Iran, President Bush claimed that "All options were on the table". According to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientist, Bush "directly threatened Iran with a preemptive nuclear strike. It is hard to read his reply in any other way."[184] The Iranian authorities consistently replied that they were not seeking nuclear weapons as a deterrent to the United States, and instead emphasize the creation of a nuclear-arms free zone in the Middle East.[185] The policy of using nuclear weapons on a first-strike basis against non-nuclear opponents is a violation of the US Negative Security Assurance pledge not to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear members of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) such as Iran. Threats of the use of nuclear weapons against another country constitute a violation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 984 and the International Court of Justice advisory opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons.

- In December 2008, President-Elect Barack Obama gave an interview on Sunday's "Meet the Press" with host Tom Brokaw during which he said the United States needs to "ratchet up tough but direct diplomacy with Iran". He said in his view the United States needs to make it clear to the Iranians that their alleged development of nuclear weapons and funding of organizations "like Hamas and Hezbollah," and threats against Israel are "unacceptable."[186] Obama supports diplomacy with Iran without preconditions "to pressure Iran to stop their illicit nuclear program".[187] Mohamed ElBaradei has welcomed the new stance to talk to Iran as "long overdue". Iran said Obama should apologize for the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II and his administration should stop talking to the world and "listen to what others are saying."[188] In his first press interview as President, Obama told Al Arabiya that "if countries like Iran are willing to unclench their fist, they will find an extended hand from us."[189]

- In March 2009 U.S. National Intelligence Director Dennis C. Blair and Defense Intelligence Agency Director Lt. Gen. Michael D. Maples told a United States Senate Committee on Armed Services hearing that Iran has only low-enriched uranium, which there were no indications it was refining. Their comments countered ones made earlier by an Israeli general and Maples said the United States was arriving at different conclusions from the same facts.[190]

- On 7 April 2009, a Manhattan district attorney charged a financier with the suspected misuse of Manhattan banks employed to transfer money between China and Iran by way of Europe and the United States.[191] The materials in question can be used for weapons as well as civilian purposes, but some of the material can potentially be used in making engine nozzles that can withstand fiery temperatures and centrifuges that can enrich uranium into atomic fuel. The charges would carry a maximum of up to a year in jail for fifth-degree conspiracy and a maximum of four years for falsifying business records.[192] David Albright, a nuclear weapons expert who assisted in the prosecution, said that it is impossible to say how Iran used or could use the raw materials it acquired.[193]

- According to a document released by the US State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research in August 2009, Iran is unlikely to have the technical capability to produce HEU (highly enriched uranium, used for bombs) before 2013, and the US intelligence community has no evidence that Iran has yet made the decision to produce highly enriched uranium.[194]

- On 26 July 2009, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton explicitly ruled out the possibility that the Obama administration would allow Iran to produce its own nuclear fuel, even under intense international inspection.[173]

- Following the November 2009 IAEA Board of Governors resolution demanding Iran immediately stop building its newly revealed nuclear facility and freeze uranium enrichment, White House spokesman Robert Gibbs avoided mentioning sanctions but indicated harsher measures were possible unless Iran compromised: "If Iran refuses to meet its obligations, then it will be responsible for its own growing isolation and the consequences." Glyn Davies, the chief U.S. delegate to the IAEA, told reporters: "Six nations ... for the first time came together ...[and] have put together this resolution we all agreed on. That's a significant development."[142]

- A 2009 U.S. congressional research paper said that U.S. intelligence believed Iran ended "nuclear weapon design and weaponization work" in 2003.[195] The intelligence consensus was affirmed by leaders of the U.S. intelligence community.[potrzebny przypis] Some advisors within the Obama administration reaffirmed the intelligence conclusions,[196] while other "top advisers" in the Obama administration "say they no longer believe" the key finding of the 2007 National Intelligence Estimate.[197] Thomas Fingar, former Chairman of the National Intelligence Council until December 2008, said that the original 2007 National Intelligence Estimate on Iran "became contentious, in part, because the White House instructed the Intelligence Community to release an unclassified version of the report's key judgments but declined to take responsibility for ordering its release."[198] A National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) is the most authoritative written judgment concerning a national security issue prepared by the Director of Central Intelligence.[199]

- The impending opening of the Bushehr I plant in late 2010 prompted the White House to question why Iran is continuing to enrich uranium within its borders. "Russia is providing the fuel, and taking the fuel back out," White House spokesman Robert Gibbs said in August. "It, quite clearly, I think, underscores that Iran does not need its own enrichment capability if its intentions, as it states, are for a peaceful nuclear program," he said.[178]

The August 2007 agreement with the IAEA[edytuj | edytuj kod]

An IAEA report to the Board of Governors on 30 August 2007, stated that Iran's Fuel Enrichment Plant at Natanz is operating "well below the expected quantity for a facility of this design," and that 12 of the intended 18 centrifuge cascades at the plant were operating. The report stated that the IAEA had "been able to verify the non-diversion of the declared nuclear materials at the enrichment facilities in Iran," and that longstanding issues regarding plutonium experiments and HEU contamination on spent fuel containers were considered "resolved." However, the report added that the Agency remained unable to verify certain aspects relevant to the scope and nature of Iran's nuclear program.

The report also outlined a work plan agreed by Iran and the IAEA on 21 August 2007. The work plan reflected agreement on "modalities for resolving the remaining safeguards implementation issues, including the long outstanding issues." According to the plan, these modalities covered all remaining issues regarding Iran's past nuclear program and activities. The IAEA report described the work plan as "a significant step forward," but added "the Agency considers it essential that Iran adheres to the time line defined therein and implements all the necessary safeguards and transparency measures, including the measures provided for in the Additional Protocol."[200] Although the work plan did not include a commitment by Iran to implement the Additional Protocol, IAEA safeguards head Olli Heinonen observed that measures in the work plan "for resolving our outstanding issues go beyond the requirements of the Additional Protocol."[201]

According to Reuters, the report was likely to blunt Washington's push for more severe sanctions against Iran. One senior UN official familiar said U.S. efforts to escalate sanctions against Iran would provoke a nationalistic backlash by Iran that would set back the IAEA investigation in Iran.[202] In late October 2007, chief IAEA inspector Olli Heinonen described Iranian cooperation with the IAEA as "good," although much remained to be done.[203]

The November 2007 IAEA report[edytuj | edytuj kod]

The 15 November 2007, IAEA report found that on nine outstanding issues listed in the August 2007 workplan, including experiments on the P-2 centrifuge and work with uranium metals, "Iran's statements are consistent with ... information available to the agency," but it warned that its knowledge of Tehran's present atomic work was shrinking due to Iran's refusal to continue voluntarily implementing the Additional Protocol, as it had done in the past under the October 2003 Tehran agreement and the November 2004 Paris agreement. The only remaining issues were traces of HEU found at one location, and allegations by US intelligence agencies based on a laptop computer allegedly stolen from Iran which reportedly contained nuclear weapons-related designs. The IAEA report also stated that Tehran continues to produce LEU. Iran has declared it has a right to peaceful nuclear technology under the NPT, despite Security Council demands that it cease its nuclear enrichment.[204]

On 18 November 2007, President Ahmadinejad announced that he intends to consult with other Arab nations on a plan, under the auspices of the Gulf Cooperation Council, to enrich uranium in a neutral third country, such as Switzerland.[205]

The February 2008 IAEA report[edytuj | edytuj kod]

On 11 February 2008, news reports stated that the IAEA report on Iran's compliance with the August 2007 work plan would be delayed over internal disagreements over the report's expected conclusions that the major issues had been resolved.[206] French Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner stated that he would meet with IAEA Director Mohammed ElBaradei to convince him to "listen to the West" and remind him that the IAEA is merely in charge of the "technical side" rather than the "political side" of the issue.[207] A senior IAEA official denied the reports of internal disagreements and accused Western powers of using the same "hype" tactics employed against Iraq before the 2003 U.S.-led invasion to justify imposing further sanctions on Iran over its nuclear program.[208]

The IAEA issued its report on the implementation of safeguards in Iran on 22 February 2008.[209] With respect to the report, IAEA Director Mohammad ElBaradei stated that "We have managed to clarify all the remaining outstanding issues, including the most important issue, which is the scope and nature of Iran´s enrichment programme" with the exception of a single issue, "and that is the alleged weaponization studies that supposedly Iran has conducted in the past."[210]

According to the report, the IAEA shared intelligence with Iran recently provided by the US regarding "alleged studies" on a nuclear weaponization program. The information was allegedly obtained from a laptop computer smuggled out of Iran and provided to the US in mid-2004.[211] The laptop was reportedly received from a "longtime contact" in Iran who obtained it from someone else now believed to be dead.[212] A senior European diplomat warned "I can fabricate that data," and argued that the documents look "beautiful, but is open to doubt".[212] The United States has relied on the laptop to prove that Iran intends to develop nuclear weapons.[212] In November 2007, the United States National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) believed that Iran halted an alleged active nuclear weapons program in fall 2003.[213] Iran has dismissed the laptop information as a fabrication, and other diplomats have dismissed the information as relatively insignificant and coming too late.[214]

The February 2008 IAEA report states that the Agency has "not detected the use of nuclear material in connection with the alleged studies, nor does it have credible information in this regard."[209]

The May 2008 IAEA report[edytuj | edytuj kod]

On 26 May 2008, the IAEA issued another regular report on the implementation of safeguards in Iran.[215]