Bawolec: Różnice pomiędzy wersjami

| [wersja przejrzana] | [wersja nieprzejrzana] |

m polska nazwa za „Polskie nazewnictwo ssaków świata” , źródła/przypisy |

z en.wiki 717297026 |

||

| Linia 1: | Linia 1: | ||

{{Zwierzę infobox |

{{Zwierzę infobox |

||

|nazwa |

|nazwa zwyczajowa = Bawolec krowi |

||

|nazwa |

|nazwa łacińska = ''Alcelaphus buselaphus'' |

||

|TSN = |

|TSN = 625077 |

||

|zoolog = |

|zoolog = ([[Peter Simon Pallas|Pallas]], 1766) |

||

|okres istnienia = |

|okres istnienia = |

||

|grafika = |

|grafika = Coke's_Hartebeest.jpg |

||

|opis grafiki = |

|opis grafiki = |

||

|gromada = [[ssaki]] |

|gromada = [[ssaki]] |

||

|podgromada = [[żyworodne]] |

|podgromada = [[żyworodne]] |

||

| Linia 13: | Linia 13: | ||

|rodzina = [[wołowate]] |

|rodzina = [[wołowate]] |

||

|podrodzina = [[bawolce]] |

|podrodzina = [[bawolce]] |

||

|rodzaj = |

|rodzaj = [[bawolec]] |

||

| |

|gatunek = '''bawolec krowi''' |

||

|synonimy = |

|synonimy =* ''Antilope bubalis'' <small>(Pallas, 1767)</small> |

||

* ''Antilope buselaphus'' <small>(Pallas, 1766)</small> |

|||

|ranga podtaksonu = [[Gatunek (biologia)|Gatunki]] |

|||

* ''Bubalis buselaphus'' <small>([[Martin Lichtenstein|Lichtenstein]], 1814)</small> |

|||

|podtaksony = |

|||

|ranga podtaksonu = [[Podgatunek|Podgatunki]] |

|||

* ''A. buselaphus'' |

|||

|podtaksony = * † ''A. b. buselaphus'' <small>(Pallas, 1766)</small> |

|||

* ''A. caama'' |

|||

* ''A. b. cokii'' <small>([[Albert Günther|Günther]], 1884)</small> |

|||

* ''A. lichtensteinii'' |

|||

* ''A. b. lelwel'' <small>(Heuglin, 1877)</small> |

|||

|wikispecies = Alcelaphus |

|||

* ''A. b. major'' <small>([[Edward Blyth|Blyth]], 1869)</small> |

|||

|commons = Alcelaphus |

|||

* ''A. b. swaynei'' <small>([[Philip Lutley Sclater|P. L. Sclater]], 1892)</small> |

|||

* ''A. b. tora'' <small>([[John Edward Gray|Gray]], 1873)</small> |

|||

* ''A. b. caama'' <small>([[Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire|Saint-Hilaire]], 1803)</small> |

|||

* ''A. b. lichtensteinii'' <small>([[Wilhelm Peters|Peters]], 1849)</small> |

|||

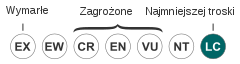

|status IUCN = LC |

|||

|IUCN id = 811/0 |

|||

|mapa występowania = Alcelaphus recent.png |

|||

|opis mapy występowania = |

|||

|wikispecies = Alcelaphus buselaphus |

|||

|commons = Alcelaphus buselaphus |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Bawolec'''{{r|miiz}} (''Alcelaphus'') – [[Rodzaj (biologia)|rodzaj]] dużych [[ssaki|ssaków]] z rodziny [[wołowate|wołowatych]]. Początkowo obejmował tylko jeden gatunek ([[bawolec krowi]]) z wieloma [[Podgatunek|podgatunkami]]. Na podstawie dokładniejszych badań niektóre podgatunki zostały wydzielone jako odrębne [[Gatunek (biologia)|gatunki]]. |

|||

The '''hartebeest''' ({{ipa-en|\ˈhär-tə-ˌbēst\|pron}}), also known as '''kongoni''', is an [[Africa]]n [[antelope]], first [[Scientific description|described]] by the German zoologist [[Peter Simon Pallas]] in 1766. Eight [[subspecies]] have been described, including two sometimes considered to be independent species. A large antelope, the hartebeest stands just over {{convert|1|m|ft|abbr=on}} at the shoulder, and has a typical head-and-body length of {{convert|200|to|250|cm|in|abbr=on}}. The weight ranges from {{convert|100|to|200|kg|lb|abbr=on}}. It has a particularly elongated forehead and oddly shaped horns, short neck, and pointed ears. Its legs, which often have black markings, are unusually long. The coat is generally short and shiny. Coat colour varies by the subspecies, from the sandy brown of the western hartebeest to the chocolate brown of the Swayne's hartebeest. Both sexes of all subspecies have horns, with those of females being more slender. Horns can reach lengths of {{convert|45|-|70|cm|in|abbr=on}}. Apart from its long face, the large chest and the sharply sloping back differentiate the hartebeest from other antelopes. |

|||

Gatunki bawolców{{r|miiz}}: |

|||

* [[bawolec krowi]] (''Alcelaphus buselaphus'') |

|||

* [[bawolec rudy]] (''Alcelaphus caama'') – (dawniej: [[Kama (antylopa)|kama]]) |

|||

* [[bawolec masajski]] (''Alcelaphus cokii'') |

|||

* [[bawolec sawannowy]] (''Alcelaphus lelwel'') |

|||

* [[bawolec esowatorogi]] (''Alcelaphus lichtensteinii'') – (dawniej: [[konzi]]) |

|||

* [[bawolec erytrejski]] (''Alcelaphus tora'') |

|||

Gregarious animals, hartebeest form herds of 20 to 300 individuals. They are very alert and non-aggressive. They are primarily grazers, with their diets consisting mainly of grasses. Mating in hartebeest takes place throughout the year with one or two peaks, and depends upon the subspecies and local factors. Both males and females reach [[sexual maturity]] at one to two years of age. [[Gestation]] is eight to nine months long, after which a single calf is born. Births usually peak in the dry season. The lifespan is 11 to 20 years in the wild and up to 19 years in captivity. |

|||

== Bibliografia == |

|||

# {{cytuj stronę| url = http://www.ultimateungulate.com/Cetartiodactyla/Alcelaphinae.html |

|||

| tytuł = Subfamily Alcelaphinae – Sassabies, hartebeests, and wildebeests |

|||

| opublikowany = ultimateungulate.com |

|||

| data dostępu = 6 grudnia 2007 |

|||

| autor = Huffman Brent |

|||

| język = en }} |

|||

# {{MSW3|id=14200496|nazwa=''Alcelaphus''| data = 6 grudnia 2007}} |

|||

Inhabiting dry [[savanna]]s and wooded grasslands, hartebeest often move to more arid places after rainfall. They have been reported from altitudes on [[Mount Kenya]] up to {{convert|4000|m|ft|abbr=on}}. The hartebeest was formerly widespread in Africa, but populations have undergone drastic decline due to habitat destruction, hunting, human settlement, and competition with livestock for food. Each of the eight subspecies of the hartebeest has a different conservation status. The [[Bubal hartebeest]] was declared [[Extinction|extinct]] by the [[International Union for Conservation of Nature]] (IUCN) in 1994. While the populations of the red hartebeest are on the rise, those of the Tora hartebeest, already [[Critically Endangered]], are falling. The hartebeest is extinct in Algeria, Egypt, Lesotho, Libya, Morocco, Somalia, and Tunisia; but has been [[introduced species|introduced]] into [[Swaziland]] and [[Zimbabwe]]. It is a popular [[game animal]] due to its highly regarded meat. |

|||

{{Przypisy|przypisy |

|||

* <ref name=miiz>{{Cytuj książkę | autor = Włodzimierz Cichocki, Agnieszka Ważna, Jan Cichocki, Ewa Rajska, Artur Jasiński, Wiesław Bogdanowicz | tytuł = Polskie nazewnictwo ssaków świata | wydawca = [[Muzeum i Instytut Zoologii PAN w Warszawie]] | miejsce = Warszawa | rok = 2015 | isbn = 978-83-88147-15-9 | strony = 297}}</ref> |

|||

==Etymology== |

|||

The vernacular name "hartebeest" ({{ipa-en|\ˈhär-tə-ˌbēst\|pron}})<ref name=MW/> could have originated from the obsolete [[Afrikaans]] word ''hertebeest'',<ref name=mares>{{cite book|last=Mares|first=M. A.|title=Encyclopedia of Deserts|year=1999|publisher=University of Oklahoma Press|location=Norman, USA|isbn=978-0-8061-3146-7|page=265}}</ref> while another supposed origin of the name is from the combination of the Dutch words ''hert'' (deer) and ''beest'' (beast).<ref name=MW>{{MerriamWebsterDictionary|Hartebeest|accessdate=24 January 2016}}</ref> The name was given by the [[Boer]]s, based on the resemblance of the antelope to [[deer]].<ref name=Llewellyn1936>{{cite book|last=Llewellyn|first=E. C.|title=The Influence of Low Dutch on the English Vocabulary|year=1936|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=London, UK|url=http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/llew001infl01_01/llew001infl01_01_0016.htm|chapter=The Influence of South African Dutch or Afrikaans on the English Vocabulary|page=163}}</ref> The first use of the word "hartebeest" in South African literature was in Dutch colonial administrator [[Jan van Riebeeck]]'s journal ''Daghregister'' in 1660. He wrote: "''Meester Pieter ein hart-beest geschooten hadde'' (Master Pieter [van Meerhoff] had shot one hartebeest)".<ref name=skinner>{{cite book|last1=Skinner|first1=J. D.|last2=Chimimba|first2=C. T.|title=The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion|year=2005|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=Cambridge, UK|isbn=978-0-521-84418-5|edition=3rd|page=649}}</ref> Another name for the hartebeest is ''kongoni'',<ref name=kingdon2013/> a [[Swahili language|Swahili]] word.<ref name=MW2>{{MerriamWebsterDictionary|Kongoni|accessdate=26 January 2016}}</ref> ''Kongoni'' is often used to refer in particular to one of its [[subspecies]]—[[Coke's hartebeest]].<ref name="swank">{{cite book|last1=Swank|first1=W. G.|title=African Antelope|date=1971|publisher=Winchester Press|location=New York, USA|isbn=978-0-87691-029-0|page=95}}</ref> |

|||

==Taxonomy== |

|||

The [[scientific name]] of the hartebeest is ''Alcelaphus buselaphus''. First [[species description|described]] by German zoologist [[Peter Simon Pallas]] in 1766, it is classified in the genus ''[[Alcelaphus]]'' and placed in the family [[Bovidae]].<ref name=MSW3>{{cite book| editor-last = Wilson | editor-first = D. E.| editor2-last = Reeder | editor2-first = D. M.| year = 2005| title = Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference| url = http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=14200497| edition = 3rd| publisher = Johns Hopkins University Press| location = Baltimore, USA| page = 674| isbn= 978-0-8018-8221-0| oclc= 62265494| ref =harv}}</ref> In 1979, palaeontologist [[Elisabeth Vrba]] supported ''[[Sigmoceros]]'' as a separate genus for [[Lichtenstein's hartebeest]], a kind of hartebeest, as she assumed it was related to ''[[Connochaetes]]'' (wildebeest).<ref name=nowak>{{cite book|last=Nowak|first=R. M.|title=Walker's Mammals of the World|year=1999|publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|location=Baltimore, USA|isbn=978-0-8018-5789-8|pages=1181–3|edition=6th}}</ref><ref name=flagstad2001/> She had analysed the skull characters of living and extinct species of antelope to make a cladogram, and argued that a wide skull linked Lichtenstein's hartebeest with ''Connochaetes''.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Vrba|first=E. S.|date=1979|title=Phylogenetic analysis and classification of fossil and recent Alcelaphini Mammalia: Bovidae|journal=Biological Journal of the Linnean Society|volume=11|issue=3|pages=207–28 |doi=10.1111/j.1095-8312.1979.tb00035.x}}</ref> However, this finding was not replicated by Alan W. Gentry of the [[Natural History Museum, London|Natural History Museum]], who classified it as an independent species of ''Alcelaphus''.<ref>{{cite book | title=Horns, Pronghorns, and Antlers: Evolution, Morphology, Physiology, and Social Significance | last1=Gentry |first1= A. W. | page=216 | editor1-last =Bubenik |editor1-first = G. A. |editor2-last = Bubenik |editor2-first= A. B. | chapter = Evolution and dispersal of African Bovidae | publisher=Springer | year=2012 | location=New York, USA | isbn=978-1-4613-8966-8}}</ref> Zoologists such as [[Jonathan Kingdon]] and [[Theodor Haltenorth]] considered it to be a subspecies of ''A. buselaphus''.<ref name=MSW3/> Vrba dissolved the new genus in 1997 after reconsideration.<ref name=groves>{{cite book|last1=Groves|first1=C.|last2=Grubb|first2=P.|title=Ungulate Taxonomy|year=2011|publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|location=Baltimore, USA|isbn=978-1-4214-0093-8|page=208}}</ref> An [[MtDNA]] analysis could find no evidence to support a separate genus for Lichtenstein's hartebeest. It also showed the tribe [[Alcelaphini]] to be [[monophyletic]], and discovered close affinity between the ''Alcelaphus'' and the sassabies (genus ''[[Damaliscus]]'')—both genetically and morphologically.<ref name=matthee>{{cite journal|last1=Matthee|first1=C. A.|last2=Robinson|first2=T. J.|title=Cytochrome b phylogeny of the family Bovidae: Resolution within the Alcelaphini, Antilopini, Neotragini, and Tragelaphini|journal=Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution|date=1999|volume=12|issue=1|pages=31–46|doi=10.1006/mpev.1998.0573|pmid=10222159}}</ref> |

|||

===Subspecies=== |

|||

[[File:Hartebeests.jpg|thumb|right|Hartebeest subspecies: Bubal hartebeest (centre); (clockwise from top-left corner) red hartebeest, Lelwel hartebeest, Swayne's hartebeest, western hartebeest, Neumann's hartebeest, Lichtenstein's hartebeest, Coke's hartebeest and Tora hartebeest, from ''Great and Small Game of Africa'']] |

|||

Eight subspecies are identified, of which two – ''A. b. caama'' and ''A. b. lichtensteinii'' – have been considered to be independent species. However, a 1999 genetic study by P. Arctander of the [[University of Copenhagen]] and colleagues, which sampled the [[mtDNA control region|control region]] of the [[mitochondrial DNA]], found that these two formed a clade within ''A. buselaphus'', and that recognising these as species would render ''A. buselaphus'' [[paraphyletic]] (an unnatural grouping). The same study found ''A. b. major'' to be the most divergent, having branched off before the lineage split to give a combined ''caama/lichtensteinii'' lineage and another that gave rise to the remaining [[Extant taxon|extant]] subspecies.<ref name=arctander>{{cite journal|last1=Arctander|first1=P.|last2=Johansen|first2=C.|last3=Coutellec-Vreto|first3=M. A.|title=Phylogeography of three closely related African bovids (tribe Alcelaphini)|journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution|date= 1999|volume=16|issue=12|pages=1724–39|pmid=10605114}}</ref> Conversely a 2001 [[Phylogenetics|phylogenetic]] study, based on [[D-loop|D–loop]] and [[cytochrome b]] analysis by Øystein Flagstad (of the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, [[Trondheim]]) and colleagues, found that the southern lineage of ''A. b. caama'' and ''A. lichtensteinii'' diverged earliest.<ref name=flagstad2001/> Analysis of skull structure supports partition into three major divisions: ''A. b. buselaphus'' division ([[Nominate (taxonomy)|nominate]], also including ''A. b. major'' division), ''A. b. tora'' division (also including ''A. b. cokii'' and ''A. b. swaynei'') and ''A. b. lelwel'' division.<ref name=MSW3/> Another analysis of cytochrome b and D-loop sequence data shows a notable [[Affinity (taxonomy)|affinity]] between the ''A. b. lelwel'' and ''A. b. tora '' divisions.<ref name=flagstad2000>{{cite journal|last1=Flagstad|first1=Ø.|last2=Syvertsen|first2=P. O.|last3=Stenseth|first3=N. C.|last4=Stacy|first4=J. E.|last5=Olsaker|first5=I.|last6=Røed|first6=K. H.|last7=Jakobsen|first7=K. S.|title=Genetic variability in Swayne's hartebeest, an endangered antelope of Ethiopia|journal=Conservation Biology|date=2000|volume=14|issue=1|pages=254–64|doi=10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.98339.x}}</ref> |

|||

The eight subspecies, including the two controversial ones, are:<ref name=iucn/><ref name=ITIS>{{ITIS|id=625077|taxon=''Alcelaphus buselaphus''|accessdate=7 April 2016}}</ref> |

|||

* † '''''A. b. buselaphus''''' <small>(Pallas, 1766)</small> : Known as the [[Bubal hartebeest]] or northern hartebeest. Formerly occurred across northern Africa, from [[Morocco]] to [[Egypt]]. It was exterminated by the 1920s.<ref name=east/> It was declared extinct in 1994 by the [[International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources]] (IUCN).<ref name=bubal>{{IUCN2008 |assessors=IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group |year=2008 |title=Alcelaphus buselaphus buselaphus|id=813 |downloaded=20 January 2013}}</ref><ref name=mallon>{{cite book|last1=Mallon|first1=D. P.|last2=Kingswood|first2=S. C.|title=Antelopes: North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia|year=2001|publisher=IUCN|location=Gland, Switzerland|isbn=978-2-8317-0594-1|page=25}}</ref> |

|||

* '''''A. b. caama''''' <small>([[Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire|Saint-Hilaire]], 1803)</small> : Known as the [[red hartebeest]] or Cape hartebeest. Formerly occurred in southern [[Angola]]; northern and eastern savannahs of [[Namibia]]; central, southern and southwestern [[Botswana]]; [[Northern Cape]], [[Eastern Cape]], [[Western Cape]], [[Free State (province)|Free State]], [[Northwest Province (South Africa)|Northwest]] and [[Gauteng]] provinces and western [[KwaZulu-Natal]] of South Africa. Presently has been eliminated from all these areas except Northern Cape, central and southwestern Botswana and Namibia. Major re-introductions have taken place in these countries.<ref name=east/> The population of this hartebeest is on the rise.<ref name=caama>{{IUCN2008 |assessors=IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group |year=2008 |title=Alcelaphus buselaphus caama|id=814 |downloaded=20 January 2013}}</ref> |

|||

* '''''A. b. cokii''''' <small>([[Albert Günther|Günther]], 1884)</small>: Known as Coke's hartebeest or kongoni. Native to and confined within [[Kenya]] and northern [[Tanzania]].<ref name=east/> |

|||

* '''''A. b. lelwel''''' <small>(Heuglin, 1877)</small> : Known as the [[Lelwel hartebeest]]. Formerly found in northern and northeastern [[Democratic Republic of the Congo]]; southeastern and southwestern [[Sudan]]; and the northwestern extreme of [[Tanzania]].<ref name=east>{{cite book|last1=East|first1=R.|last2=IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group|title=African Antelope Database 1998|date=1999|publisher=The IUCN Species Survival Commission|location=Gland, Switzerland|isbn=978-2-8317-0477-7|pages=186–93}}</ref> Drastic population decrease since the 1980s has confined most individuals to protected areas inside and outside its range.<ref name=lelwel>{{IUCN2008 |assessors=IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group |year=2008 |title=Alcelaphus buselaphus lelwel|id=816 |downloaded=23 January 2013}}</ref> |

|||

* '''''A. b. lichtensteinii''''' <small>([[Wilhelm Peters|Peters]], 1849)</small> : Known as Lichtenstein's hartebeest. Inhabits the [[miombo woodland]]s of eastern and southern Africa.<ref name=rafferty1>{{cite book|last=Rafferty|first=J. P.|title=Grazers|year=2010|publisher=Britannica Educational Publications|location=New York, USA|isbn=978-1-61530-465-3|edition=1st|page=121}}</ref> It is native to Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, [[Malawi]], [[Mozambique]], South Africa, Tanzania, [[Zambia]] and [[Zimbabwe]].<ref>{{IUCN2008 |assessors=IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group |year=2008 |title=Alcelaphus buselaphus lichtensteini|id=812|downloaded=20 January 2013}}</ref> |

|||

* '''''A. b. major''''' <small>([[Edward Blyth|Blyth]], 1869)</small> : Known as the [[western hartebeest]]. Formerly occurred widely in Mali, [[Niger]], [[Senegal]], [[Gambia]], [[Guinea-Bissau]], [[Guinea]], [[Ivory Coast]], [[Ghana]], [[Nigeria]], southwestern Chad, Cameroon, western Central African Republic and [[Benin]]. Nowadays it occurs in much lower numbers mainly in protected areas of these countries. It is probably extinct in Gambia.<ref name=east/> |

|||

* '''''A. b. swaynei''''' <small>([[Philip Sclater|Sclater]], 1892)</small> : Known as [[Swayne's hartebeest]]. Restricted to the southern [[Rift Valley]] in Ethiopia. It formerly occurred throughout the Rift Valley, and its range extended eastward into northwestern [[Somalia]]. It has disappeared from Somalia by 1930.<ref name=east/> Its populations are very low and on the decline.<ref name=lewis>{{cite journal|last=Lewis|first=J. G.|last2=Wilson|first2=R. T.|title=The plight of Swayne's hartebeest|journal=Oryx|year=1977|volume=13|issue=5|pages=491–4|doi=10.1017/S0030605300014551}}</ref> |

|||

* '''''A. b. tora''''' <small>([[John Edward Gray|Gray]], 1873)</small> : Known as the [[Tora hartebeest]]. Formerly occurred in northwestern Ethiopia and western and southwestern [[Eritrea]].<ref name=hildyard/> Its present status is unclear, though locals have reported small numbers from these areas.<ref name=east/> |

|||

{{Gallery |

|||

|title=Five hartebeest subspecies |

|||

|width=200 |

|||

|height=200 |

|||

|lines=1 |

|||

|align=center |

|||

|File:The book of antelopes (1894) Bubalis busephalus.png|Bubal hartebeest |

|||

|File:The book of antelopes (1894) Bubalis caama.png|Red hartebeest |

|||

|File:The book of antelopes (1894) Bubalis cokei.png|Coke's hartebeest |

|||

|File:The book of antelopes (1894) Bubalis lichtensteini.png|Liechtenstein's hartebeest |

|||

|File:The book of antelopes (1894) Bubalis swaynei.png|Swayne's hartebeest |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

===Genetics and hybrids=== |

|||

[[Kategoria:Wołowate| ]] |

|||

In 2000, a study scrutinised two major populations of the Swayne's hartebeest, from the [[Senkele Wildlife Sanctuary]] and the [[Nechisar National Park]], for mitochondrial (D-loop) and nuclear ([[microsatellite]]) variability in an attempt to estimate the levels of [[genetic variation]] between the populations and within the subspecies. The results showed a remarkable differentiation between the two populations; that from the Senkele Wildlife Sanctuary showed more [[genetic diversity]] than the one from the Nechisar National Park. Another revelation was that the [[Translocation (wildlife conservation)|translocation]] of the individuals from the Senkele Wildlife Sanctuary in 1974 had not made a significant contribution to the gene pool of the Nechisar National Park. Additionally, the Swayne hartebeest populations were compared with a large red hartebeest population, and both subspecies were found to have a high degree of genetic variation. The study advocated [[in situ conservation]] of the Swayne's hartebeest and a renewed attempt at its translocation in order to conserve genetic diversity and increase its population size in both the protected areas.<ref name=flagstad2000/> |

|||

The [[diploid]] number of chromosomes in the hartebeest is 40. Hybrids are usually reported from areas where ranges of two subspecies overlap.<ref name=kingdon2013/> Hybrids between the Lelwel and Tora hartebeest have been reported in eastern Sudan and western Ethiopia, in a stretch southward from the [[Blue Nile]] to about 9° N latitude.<ref name=lelwelsci/> A study proved a male hybrid of the red hartebeest and the [[blesbok]] (''Damaliscus pygargus'') to be [[Sterility (physiology)|sterile]]. Sterility of the hybrid was attributed to difficulties in [[Mendel's laws|segregation]] during [[meiosis]], indicated by [[azoospermia]] and a low number of [[germ cell]]s in its [[seminiferous tubule]]s.<ref name=robinson>{{cite journal|last1=Robinson|first1=T. J.|last2=Morris|first2=D. J.|last3=Fairall|first3=N.|title=Interspecific hybridisation in the Bovidae: Sterility of ''Alcelaphus buselaphus'' × ''Damaliscus dorcas'' F1 progeny|journal=Biological Conservation|date=1991|volume=58|issue=3|pages=345–56|doi=10.1016/0006-3207(91)90100-N}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Flickr - Rainbirder - Jackson's Hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus lelwel).jpg|thumb|Jackson's hartebeest]] |

|||

There are three common cross-breeds between the subspecies: |

|||

* ''Alcelaphus lelwel x cokii'': Known as the Kenya Highland hartebeest or the Laikipia hartebeest. It is a cross between the Lelwel and Coke's hartebeest.<ref name=castello/> This hybrid is lighter in colour and larger than Coke's hartebeest. It is a light buff with reddish-tawny upper parts, and the head is longer than in Coke's hartebeest. Both sexes have horns, which are heavier as well as longer than those of the parents. It was formerly distributed throughout the western Kenyan highlands, between [[Lake Victoria]] and [[Mount Kenya]], but is now believed to be restricted to the Lambwe Valley (south-west Kenya) and [[Laikipia District|Laikipia]] and nearby regions of west-central Kenya.<ref name=Augustine2011>{{cite book|last1=Augustine|first1=D. J.|last2=Veblen|first2=K. E.|last3=Goheen|first3=J. R.|last4=Riginos|first4=C.|last5=Young|first5=T. P.|chapter=Pathways for positive cattle–wildlife interactions in semiarid rangelands|title=Conserving Wildlife in African Landscapes: Kenya's Ewaso Ecosystem|editor=Georgiadis, N. J.|date=2011|location= Washington D.C., USA|publisher=Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press|series=Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology|volume=632|pages=55–71|url=https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/16714/SCZ632_Georgiadis_web_FINALrev.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y}}</ref><ref name=kenyasci>{{cite web|title=Kenya Highland Hartebeest|url=http://www.scirecordbook.org/kenya-highland-hartebeest/|website=Big Game Hunting Records – Safari Club International Online Record Book|publisher=[[Safari Club International]]|accessdate=26 January 2016}}</ref> |

|||

* ''Alcelaphus lelwel x swaynei'' : Also known as the Neumann's hartebeest, named after traveller and hunter [[Arthur Henry Neumann]].<ref name=ruxton>{{cite journal|last1=Ruxton|first1=A. E.|last2=Schwarz|first2=E.|title= On hybrid hartebeests and on the distribution of the ''Alcelaphus buselaphus'' group|journal=Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London|year=1929|volume=99|issue=3|pages=567–83|doi=10.1111/j.1469-7998.1929.tb07706.x}}</ref> This is considered to be a cross between the Lelwel hartebeest and Swayne's hartebeest.<ref name=castello>{{cite book|last1=Castelló|first1=J. R.|title=Bovids of the World: Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives|date=2016|publisher=Princeton University Press|location=Princeton, USA|isbn=978-0-691-16717-6|pages=537–9}}</ref> The face is longer than that of the Swayne's hartebeest. The colour of the coat is a golden brown, paler towards the underparts. The chin has a hint of black and the tail ends in a black tuft. Both sexes have longer horns than the Swayne's hartebeest. The horns grow in a wide "V" shape, unlike the wide bracket shape of Swayne's hartebeest and the narrow "V" of Lelwel hartebeest, curving backward and slightly inward. It occurs in Ethiopia, in a small area to the east of [[Omo River]] and north of [[Lake Turkana]], stretching north-east of [[Lake Chew Bahir]] to near [[Lake Chamo]].<ref name=neumannsci>{{cite web|title=Neumann Hartebeest|url=http://www.scirecordbook.org/neumann-hartebeest/|website=Big Game Hunting Records – Safari Club International Online Record Book|publisher=[[Safari Club International]]|accessdate=26 January 2016}}</ref> |

|||

* The Jackson's hartebeest does not have a clear taxonomic status. It is regarded as a hybrid between the Lelwel and Coke's hartebeest. The ''African Antelope Database'' (1998) treats it as synonymous to the Lelwel hartebeest.<ref name=east/> From Lake Baringo to Mount Kenya, the Jackson's hartebeest significantly resembles the Lelwel hartebeest, whereas from Lake Victoria to the southern part of the Rift Valley it tends to be more like the Coke's hartebeest.<ref name=ruxton/> |

|||

==Evolution== |

|||

The genus ''Alcelaphus'' emerged about 4.4 million years ago in a [[clade]] whose other members were ''[[Damalops]]'', ''[[Numidocapra]]'', ''[[Rabaticeras]]'', ''[[Megalotragus]]'', ''[[Oreonagor]]'', and ''Connochaetes''. An analysis using [[Phylogeography|phylogeographic]] patterns within hartebeest populations suggested a possible origin of ''Alcelaphus'' in eastern Africa.<ref name=Harris>{{cite book|last1=Harris|first1=J.|last2=Leaky|first2=M.|title=Lothagam: The Dawn of Humanity in Eastern Africa|year=2001|publisher=Columbia University Press|location=New York, USA|isbn=978-0-231-11870-5|page=547}}</ref> ''Alcelaphus'' quickly [[evolutionary radiation|radiated]] across the African savannas, replacing several previous forms (such as a relative of the [[hirola]]). Flagstad and colleagues showed an early split in the hartebeest populations into two distinct lineages around 0.5 million years ago – one to the north and the other to the south of the equator. The northern lineage further diverged into eastern and western lineages, nearly 0.4 million years ago, most probably as a result of the expanding [[African rainforest|central African rainforest]] belt and subsequent contraction of [[savannah]] habitats during a period of global warming. The eastern lineage gave rise to the Coke's, Swayne's, Tora and Lelwel hartebeest; and from the western lineage evolved the Bubal and western hartebeest. The southern lineage gave rise to Lichtenstein's and red hartebeest. These two taxa are phylogenetically close, having diverged only 0.2 million years ago. The study concluded that these major events throughout the hartebeest's evolution are strongly related to climatic factors, and that there had been successive bursts of radiation from a more permanent population—a [[Refugium (population biology)|refugium]]—in eastern Africa; this could be vital to understanding the evolutionary history of not only the hartebeest but also other mammals of the African savanna.<ref name=flagstad2001>{{cite journal|last1=Flagstad|first1=Ø.|last2=Syversten|first2=P. O.|last3=Stenseth|first3=N. C.|last4=Jakobsen|first4=K. S.|title=Environmental change and rates of evolution: the phylogeographic pattern within the hartebeest complex as related to climatic variation|journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences|date=2001|volume=268|issue=1468|pages=667–77|doi=10.1098/rspb.2000.1416|pmid=11321054}}</ref><!-- cites most of paragraph --> |

|||

The earliest fossil record dates back to nearly 0.7 million years ago.<ref name=kingdon2013>{{cite book|last1=Kingdon|first1=J.|title=Mammals of Africa|date=2013|publisher=Bloomsbury|location=London, UK|isbn=978-1-4081-2257-0|pages=510–22}}</ref> Fossils of the [[red hartebeest]] have been found in Elandsfontein, [[Cornelia, Free State|Cornelia (Free State)]] and [[Florisbad archaeological and paleontological site|Florisbad]] in [[South Africa]], as well as in [[Kabwe]] in [[Zambia]].<ref name=berger>{{cite book|last1=Berger|first1=L. R.|last2=Hilton-Barber|first2=B.|title=Field Guide to the Cradle of Humankind: Sterkfontein, Swartkrans, Kromdraai & Environs World Heritage Site|year=2004|publisher=Struik Publishers|location=Cape Town, South Africa|isbn=978-1-77007-065-3|edition=2nd (revised)|page=163}}</ref> In [[Israel]], hartebeest remains have been found in northern [[Negev]], [[Shephelah]], [[Sharon Plain]] and [[Tel Lachish]]. This population of the hartebeest was originally limited to the open country of the southernmost regions of the southern [[Levant]]. It was probably hunted in Egypt, which affected the numbers in the Levant, and disconnected it from its main population in Africa.<ref name=tsahar>{{cite journal|last1=Tsahar|first1=E.|last2=Izhaki|first2=I. |last3=Lev-Yadun|first3=S. |last4=Bar-Oz|first4=G. |last5= Hansen|first5=D. M. |title=Distribution and extinction of ungulates during the Holocene of the southern Levant |journal=PLoS ONE|year=2009|volume=4|issue=4|pages=5316–28|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0005316|bibcode=2009PLoSO...4.5316T}} {{open access}}</ref> |

|||

==Description== |

|||

[[File:Alcelaphus caama.jpg|thumbnail|300px|left|A red hartebeest showing the dark face, black tail, white rump and V-shaped horns]] |

|||

A large antelope with a particularly elongated forehead and oddly shaped horns, the hartebeest stands just over {{convert|1|m|ft|abbr=on}} at the shoulder, and has a typical head-and-body length of {{convert|200|to|250|cm|in|abbr=on}}. The weight ranges from {{convert|100|to|200|kg|lb|abbr=on}}. The tail, {{convert|40|to|60|cm|in|abbr=on}} long, ends in a black tuft.<ref name=kingdon>{{cite book|last=Kingdon|first=J.|title=East African Mammals: An Atlas of Evolution in Africa|volume=Volume 3, Part D: Bovids|year=1989|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|isbn=978-0-226-43725-5}}</ref> The other distinctive features of the hartebeest are its long legs (often with black markings), short neck, and pointed ears.<ref name=Macdonald>{{cite book|last=Macdonald|first=D.|title=The Encyclopedia of Mammals|year=1987|publisher=Facts on File|location=New York, USA|isbn=978-0-87196-871-5|pages=564–71}}</ref> A study correlated the size of hartebeest species to [[primary production|habitat productivity]] and rainfall.<ref name=capellini>{{cite journal|last1=Capellini|first1=I.|last2=Gosling |first2= L. M.|title=Habitat primary production and the evolution of body size within the hartebeest clade|journal=Biological Journal of the Linnean Society|year=2007|volume=92|issue=3|pages=431–40|doi=10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00883.x}}</ref> The western hartebeest is the largest subspecies, and has a characteristic white line between the eyes.<ref name=westernsci>{{cite web|title=Western Hartebeest|url=http://www.scirecordbook.org/western-hartebeest/|website=Big Game Hunting Records – Safari Club International Online Record Book|publisher=[[Safari Club International]]|accessdate=26 January 2016}}</ref> The red hartebeest is also large, with a black forehead and a contrasting light band between the eyes.<ref name=redsci>{{cite web|title=Cape or Red Hartebeest|url=http://www.scirecordbook.org/cape-or-red-hartebeest/|website=Big Game Hunting Records – Safari Club International Online Record Book|publisher=[[Safari Club International]]|accessdate=26 January 2016}}</ref> The large Lelwel hartebeest has dark stripes on the front of its legs.<ref name=lelwelsci>{{cite web|title=Lelwel Hartebeest|url=http://www.scirecordbook.org/lelwel-hartebeest/|website=Big Game Hunting Records – Safari Club International Online Record Book|publisher=[[Safari Club International]]|accessdate=26 January 2016}}</ref> Coke's hartebeest is moderately large, with a shorter forehead and longer tail in comparison to the other subspecies.<ref name=cokesci>{{cite web|title=Coke Hartebeest|url=http://www.scirecordbook.org/coke-hartebeest/|website=Big Game Hunting Records – Safari Club International Online Record Book|publisher=[[Safari Club International]]|accessdate=26 January 2016}}</ref> Lichtenstein's hartebeest is smaller, with dark stripes on the front of the legs, as in the Lelwel hartebeest.<ref name=Lsci>{{cite web|title=Lichtenstein Hartebeest|url=http://www.scirecordbook.org/lichtenstein-hartebeest/|website=Big Game Hunting Records – Safari Club International Online Record Book|publisher=[[Safari Club International]]|accessdate=26 January 2016}}</ref> The Swayne's hartebeest is smaller than the Tora hartebeest, but both have a shorter forehead and similar appearance.<ref name=swaynesci>{{cite web|title=Swayne Hartebeest|url=http://www.scirecordbook.org/swayne-hartebeest/|website=Big Game Hunting Records – Safari Club International Online Record Book|publisher=[[Safari Club International]]|accessdate=26 January 2016}}</ref> |

|||

Generally short and shiny, the coat varies in colour according to subspecies.<ref name=estes/> The western hartebeest is a pale sandy-brown, but the front of the legs are darker.<ref name=westernsci/> The red hartebeest is a reddish-brown, with a dark face. Black markings can be observed on the chin, the back of the neck, shoulders, hips and legs; these are in sharp contrast with the broad white patches that mark its flanks and lower rump.<ref name=redsci/><ref name=wwsa>{{cite book|last=Firestone|first=M.|title=Watching Wildlife: Southern Africa; South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia|year=2009|publisher=Lonely Planet|location=Footscray, Australia|isbn=978-1-74104-210-8|pages=228–9|edition=2nd}}</ref> The Lelwel hartebeest is a reddish tan.<ref name=lelwelsci/> Coke's hartebeest is reddish to tawny in the upper parts, but has relatively lighter legs and rump.<ref name=cokesci/> Lichtenstein's hartebeest is reddish brown, though the flanks are a lighter tan and the rump whitish.<ref name=Lsci/> The Tora hartebeest is a dark reddish brown in the upper part of the body, the face, the forelegs and the rump, but the hindlegs and the underbelly are a yellowish white.<ref name=hildyard>{{cite book|last=Hildyard|first=A.|title=Endangered Wildlife and Plants of the World|year=2001|publisher=Marshall Cavendish|location=New York, USA|isbn=978-0-7614-7199-8|pages=674–5}}</ref><ref name=heckel>{{cite journal|last1=Heckel|first1=J. O.|title=The present status of the hartebeest subspecies with special focus on north-east Africa an the Tora hartebeest|date=2007|pages=1–13|url=http://www.ewca.gov.et/sites/default/files/Hartebeest%20subspeciesHeckel.pdf|accessdate=26 January 2016|publisher=Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority}}</ref> The Swayne's hartebeest is a rich chocolate brown with fine spots of white that are actually the white tips of its hairs. Its face is black save for the chocolate band below the eyes. The shoulders and upper part of the legs are black.<ref name=swaynesci/> Fine textured, the body hair of the hartebeest is about {{convert|25|mm|in|0|abbr=on}} long.<ref name="nowak"/> The hartebeest has [[preorbital gland]]s (glands near the eyes) with a central duct, that secrete a dark sticky fluid in Coke's and Lichtenstein's hartebeest, and a colourless fluid in the Lelwel hartebeest.<ref name=estes/> |

|||

[[File:Alcelaphus caama (portrait).jpg|thumbnail|A close head-shot of a red hartebeest]] |

|||

Both sexes of all subspecies have horns, with those of females being more slender. Horns can reach lengths of {{convert|45|-|70|cm|in|abbr=on}}; the maximum horn length is {{convert|74.9|cm|in|abbr=on}}, recorded from a Namibian red hartebeest.<ref name=kingdon/> The horns of the western hartebeest are thick and appear U-shaped from the front and Z-shaped from the sides, growing backward at first and then forward, ending with a sharp backward turn.<ref name=westernsci/> The horns of the red and the Lelwel hartebeest are similar to those of the western hartebeest, but appear V-shaped when viewed from the front.<ref name=lelwelsci/><ref name=redsci/> The Lichtenstein's hartebeest has thick parallel ringed horns, with a flat base. Its horns are shorter than those of other subspecies, curving upward then sharply forward, followed by an inward turn at an angle of about 45° and a final backward turn.<ref name=Lsci/> The horns of Swayne's hartebeest are thin and shaped like parentheses, curving upward and then backward.<ref name=swaynesci/> The horns of the Tora hartebeest are particularly thin and spread out sideways, diverging more than in any other subspecies.<ref name=heckel/> |

|||

Apart from its long face, the large chest and the sharply sloping back differentiate the hartebeest from other antelopes.<ref name=mares/> The hartebeest shares several physical traits with the sassabies (genus ''Damaliscus''), such as an elongated and narrow face, the shape of the horns, the [[coat (animal)|pelage]] texture and colour, and the terminal tuft of the tail. The [[wildebeest]] have more specialised skull and horn features than the hartebeest.<ref name=estes/> The hartebeest exhibits [[sexual dimorphism]], but only slightly, as both sexes bear horns and have similar body masses. The degree of sexual dimorphism varies by subspecies. Males are 8% heavier than females in Swayne's and Lichtenstein's hartebeest, and 23% heavier in the red hartebeest. In one study, the highest dimorphism was found in skull weight.<ref name=capellini2>{{cite book|last=Capellini|first=I.|editor1-last=Fairbairn|editor1-first=D. J.|editor2-last=Blanckenhorn|editor2-first=W. U.|editor3-last=Székely|editor3-first=T.|chapter=Dimorphism in the hartebeest|title=Sex, Size and Gender Roles: Evolutionary Studies of Sexual Size Dimorphism|year=2007|location=London, UK|publisher=Oxford University Press|pages=124–32|isbn=978-0-19-954558-2|doi= 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199208784.003.0014}}</ref> Another study concluded that the length of the breeding season is a good predictor of dimorphism in pedicle (the bony structures from which the horns grow) height and skull weight, and the best predictor of the horn circumference.<ref name=capellini3>{{cite journal|last1=Capellini|first1=I.|last2=Gosling|first2= L. M.|title=The evolution of fighting structures in hartebeest|journal=Evolutionary Ecology Research|year=2006|volume=8|pages=997–1011|url=http://eprint.ncl.ac.uk/file_store/production/73964/47C43E06-59DC-401D-8EB5-A347757746D2.pdf}}</ref> |

|||

==Ecology and behaviour== |

|||

Active mainly during daytime, the hartebeest grazes in the early morning and late afternoon, and rests in shade around noon. [[Gregarious]], the species forms herds of up to 300 individuals. Larger numbers gather in places with abundant grass. In 1963, a congregation of 10,000 animals was recorded on the plains near Sekoma Pan in Botswana.<ref name=estes/> However, moving herds are not so cohesive, and tend to disperse frequently. The members of a herd can be divided into four groups: territorial adult males, non-territorial adult males, young males, and the females with their young. The females form groups of five to 12 animals, with four generations of young in the group. Females fight for dominance over the herd.<ref name=kingdon/> Sparring between males and females is common.<ref name=kingdon2013/> At three or four years of age, the males can attempt to take over a [[Territory (animal)|territory]] and its female members. A resident male defends his territory and will fight if provoked.<ref name=capellini2/> The male marks the border of his territory through defecation.<ref name=kingdon/> |

|||

[[File:Hardebeest.jpg|thumb|300px|right|A herd of hartebeest]] |

|||

Hartebeest are remarkably alert and cautious animals with highly developed [[brain]]s.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Oboussier|first1=H.|title=Information on Alcelaphini (Bovidae-Mammalia) with special reference to the brain and hypophysis. Results of research trips through Africa (1959–1967)|journal=Gegenbaurs morphologisches Jahrbuch|date=1970|volume=114|issue=3|pages=393–435|pmid=5523305}}</ref><ref name=schaller>{{cite book|last=Schaller|first=G. B.|title=The Serengeti Lion: A Study of Predator-Prey Relations|year=1976|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago, USA|isbn=978-0-226-73640-2|pages=461–5}}</ref> Generally calm in nature, hartebeest can be ferocious when provoked. While feeding, one individual stays on the lookout for danger, often standing on a [[termite]] mound to see farther. At times of danger, the whole herd flees in a single file after an individual suddenly starts off.<ref name=kingdon/> Adult hartebeest are preyed upon by lions, [[leopard]]s, [[hyena]]s and [[Lycaon pictus|wild dogs]]; [[cheetah]]s and [[jackal]]s target juveniles.<ref name=kingdon/> Crocodiles may also prey on hartebeest.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Eltringham|first1=S. K.|title=The Ecology and Conservation of Large African Mammals|date=1979|publisher=MacMillan|location=London, UK|isbn=978-0-333-23580-5|page=177|edition=1st}}</ref> |

|||

The thin long legs of the hartebeest provide for a quick escape in an open habitat; if attacked, the formidable horns are used to ward off the predator. The elevated position of the eyes enables the hartebeest to inspect its surroundings continuously even as it is grazing. The muzzle is designed so as to derive maximum nutrition from even a frugal diet.<ref name=kingdon2013/> The horns are also used during fights among males for [[Dominance (ethology)|dominance]] in the breeding season;<ref name=capellini3/> the clash of the horns is loud enough that it can be heard from hundreds of metres away.<ref name=kingdon2013/> The beginning of a fight is marked with a series of head movements and stances, as well as depositing droppings on dung piles. The opponents drop onto their knees and, after giving a hammer-like blow, begin wrestling, their horns interlocking. One attempts to fling the head of the other to one side to stab the neck and shoulders with his horns.<ref name=capellini2/> Fights are rarely serious, but can be fatal if they are.<ref name=estes/> |

|||

Like the sassabies, hartebeest produce quiet quacking and grunting sounds. Juveniles tend to be more vocal than adults, and produce a quacking call when alarmed or pursued.<ref name=kingdon/> The hartebeest uses defecation as an [[olfactory]] and visual display.<ref name=estes/> Herds are generally sedentary, and tend to migrate only under adverse conditions such as natural calamities.<ref name=verlinden>{{cite journal|last=Verlinden|first=A.|title=Seasonal movement patterns of some ungulates in the Kalahari ecosystem of Botswana between 1990 and 1995|journal=African Journal of Ecology|year=1998|volume=36|issue=2|pages=117–28|doi=10.1046/j.1365-2028.1998.00112.x|doi-broken-date=7 March 2016}}</ref> The hartebeest is the least migratory in the [[Tribe (biology)|tribe]] Alcelaphini (which also includes wildebeest and sassabies), and also consumes the least amount of water and has the lowest [[metabolic rate]] among the members of the tribe.<ref name=estes/> |

|||

===Parasites and diseases=== |

|||

Several [[parasite]]s have been isolated from the hartebeest.<ref name=boomker>{{cite journal|last1=Boomker|first1=J.|last2=Horak|first2=I. G.|last3=De Vos|first3=V.|title=The helminth parasites of various artiodactylids from some South African nature reserves|journal=The Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research|date=1986|volume=53|issue=2|pages=93–102|pmid=3725333}}</ref><ref name=howard/> These parasites regularly alternate between hartebeest and gazelles or wildebeest.<ref name=pester>{{cite journal|last1=Pester|first1=F. R. N.|last2=Laurence|first2=B. R.|title=The parasite load of some African game animals|journal=Journal of Zoology|date= 2009|volume=174|issue=3|pages=397–406|doi=10.1111/j.1469-7998.1974.tb03167.x}}</ref> Hartebeest can be infected with [[East coast fever|theileriosis]] due to ''[[Rhipicephalus evertsi]]'' and ''[[Theileria]]'' species.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Spitalska|first1=E.|last2=Riddell|first2=M.|last3=Heyne|first3=H.|last4=Sparagano|first4=O.A.|title=Prevalence of theileriosis in red hartebeest (''Alcelaphus buselaphus caama'') in Namibia|journal=Parasitology Research|date=2005|volume=97|issue=1|pages=77–9|doi=10.1007/s00436-005-1390-y|issn=1432-1955|pmid=15986252}}</ref> South of the [[Sahara]], common parasites include ''[[Loewioestrus variolosus]]'', ''[[Gedoelstia cristata]]'' and ''[[Gedoelstia hassleri|G. hassleri]]''. The latter two species can cause serious diseases such as [[encephalitis]].<ref name=spinage>{{cite book|last=Spinage|first=C. A.|title=African Ecology: Benchmarks and Historical Perspectives|year=2012|publisher=Springer|location=Berlin, Germany|isbn=978-3-642-22872-8|page=1176}}</ref> However, parasites are not always harmful – 252 [[Larva (zoology)|larvae]] were found in the head of one Zambian individual without any [[pathogenicity]].<ref name=howard>{{cite journal|last=Howard|first=G. W.|title=Prevalence of nasal bots (Diptera: Oestridiae) in some Zambian hartebeest|journal=Journal of Wildlife Diseases|year=1977|volume=13|issue=4|pages=400–4|doi=10.7589/0090-3558-13.4.400|pmid=24228960}}</ref> [[Nematode]]s, [[cestode]]s, [[Paramphistomum|paramphistome]]s; and the [[roundworm]] ''[[Setaria labiatopapillosa]]'' have also been isolated from the hartebeest.<ref name=belem>{{cite journal|last=Belem|first=A. M. G.|last2=Bakoné|first2=É. U.|title=Parasites gastro-intestinaux d'antilopes et de buffles (''Syncerus caffer brachyceros'') du ranch de gibier de Nazinga au Burkina Faso|trans_title=Gastro-intestinal parasites of antelopes and buffaloes (''Syncerus caffer brachyceros'') from the Nazinga game ranch in Burkina Faso|journal=Biotechnologie, Agronomie, Société et Environnement|year=2009|volume=13|issue=4|pages=493–8|issn=1370-6233|url=http://popups.ulg.ac.be/1780-4507/index.php?id=4665|language=French}} {{open access}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Hoberg|first1=E. P.|last2=Abrams|first2=A.|last3=Pilitt|first3=P. A.|title=''Robustostrongylus aferensis'' gen. nov. et sp. nov. (Nematoda: Trichostrongyloidea) in kob (''Kobus kob'') and hartebeest (''Alcelaphus buselaphus jacksoni'') (Artiodactyla) from sub-Saharan Africa, with further ruminations on the Ostertagiinae|journal=The Journal of Parasitology|date=2009|volume=95|issue=3|pages=702–17|pmid=19228080}}</ref> In 1931, a red hartebeest in [[Gobabis]] (southwestern Africa) was infected with long, thin worms. These were named ''[[Longistrongylus meyeri]]'' after their collector, T. Meyer.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Le Roux|first=P. L.|title=On ''Longistrongylus meyeri '' gen. and sp. nov., a trichostrongyle parasitizing the Red Hartebeest ''Bubalis caama''|journal=Journal of Helminthology|year=1931|volume=9|issue=3|page=141|doi=10.1017/S0022149X00030376}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Alcelaphus buselaphus, Ngorongoro, Tanzania.jpg|thumb|Hartebeest feed primarily on grasses.]] |

|||

===Diet=== |

|||

Hartebeest are primarily grazers, and their diets consist mostly of grasses.<ref name=awf>{{cite web|title=Hartebeest|url=http://www.awf.org/content/wildlife/detail/hartebeest|publisher=[[African Wildlife Foundation]]|accessdate=20 January 2013}}</ref> A study in the [[Nazinga Game Ranch]] in [[Burkina Faso]] found that the hartebeest's skull structure eased the acquisition and chewing of highly fibrous foods.<ref name=schuette/> The hartebeest has much lower food intake than the other members of Alcelaphini. The long thin [[Muzzle (animal)|muzzle]] of the hartebeest assists in feeding on leaf blades of short grasses and nibbling off leaf sheaths from grass stems. In addition to this, it can derive nutritious food even from tall senile grasses. These adaptations of the hartebeest enable the animal to feed well even in the dry season, which is usually a difficult period for grazers.<ref name=kingdon2013/> For instance, in comparison with the [[roan antelope]], the hartebeest is better at procuring and chewing the scarce regrowth of [[perennial grass]]es at times when forage is least available.<ref name=schuette/> These unique abilities could have allowed the hartebeest to prevail over other animals millions of years ago, leading to its successful radiation in Africa.<ref name=kingdon2013/> |

|||

Grasses generally comprise at least 80 percent of the hartebeest's diet, but they account for over 95 percent of their food in the wet season, October to May. ''[[Jasminum kerstingii]]'' is part of the hartebeest's diet at the start of the rainy season. Between seasons, they mainly feed on the [[Culm (plant)|culm]]s of grasses.<ref name=schuette>{{cite journal|last1=Schuette|first1=J. R.|last2=Leslie|first2=D. M.|last3=Lochmiller|first3=R. L.|last4=Jenks|first4=J. A.|title=Diets of hartebeest and Roan antelope in Burkina Faso: Support of the long-faced hypothesis|journal=Journal of Mammalogy|date=1998|volume=79|issue=2|pages=426–36|doi=10.2307/1382973}}</ref> A study found that the hartebeest is able to digest a higher proportion of food than the topi and the wildebeest.<ref name=murray>{{cite journal|last=Murray|first=M. G.|title=Comparative nutrition of wildebeest, hartebeest and topi in the Serengeti|journal=African Journal of Ecology|year=1993|volume=31|issue=2|pages=172–7|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2028.1993.tb00530.x}}</ref> In areas with scarce water, it can survive on melons, roots, and tubers.<ref name=estes/> |

|||

In a study of grass selectivity among the wildebeest, zebra, and the Coke's hartebeest, the hartebeest showed the highest selectivity. All animals preferred ''[[Themeda triandra]]'' over ''[[Pennisetum mezianum]]'' and ''[[Digitaria macroblephara]]''. More grass species were eaten in the dry season than in the wet season.<ref name=casebeer>{{cite journal|last=Casebeer|first=R. L.|last2=Koss|first2=G. G.|title=Food habits of wildebeest, zebra, hartebeest and cattle in Kenya Masailand|journal=African Journal of Ecology|year=1970|volume=8|issue=1|pages=25–36|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2028.1970.tb00827.x}}</ref> |

|||

===Reproduction=== |

|||

[[File:Red Hartebeests (Alcelaphus buselaphus) (6628347615).jpg|left|thumb|Two red hartebeest juveniles in a grassland]] |

|||

Mating in hartebeest takes place throughout the year, with one or two peaks that can be influenced by the availability of food.<ref name=awf/> Both males and females reach [[sexual maturity]] at one to two years of age. Reproduction varies by the subspecies and local factors.<ref name=nowak/> Mating takes place in the territories defended by a single male, mostly in open areas.<ref name=awf/> The males may fight fiercely for dominance,<ref name=capellini2/> following which the dominant male smells the female's genitalia, and follows her if she is in [[Estrous cycle|oestrus]]. Sometimes a female in oestrus holds out her tail slightly to signal her receptivity,<ref name=estes/> and the male tries to block the female's way. She may eventually stand still and allow the male to mount her. Copulation is brief and is often repeated, sometimes twice or more in a minute.<ref name=estes/> Any intruder at this time is chased away.<ref name=kingdon/> In large herds, females often mate with several males.<ref name=estes/> |

|||

[[Gestation]] is eight to nine months long, after which a single calf weighing about {{convert|9|kg|lb|abbr=on}} is born. Births usually peak in the dry season, and take place in thickets – unlike the wildebeest, which give birth in groups on the plains.<ref name=estes/> Though calves can move about on their own shortly after birth, they usually lie in the open in close proximity of their mothers.<ref name=castello/> The calf is weaned at four months,<ref name=castello/> but young males stay with their mothers for two and a half years, longer than in other Alcelaphini.<ref name=estes>{{cite book|last=Estes|first=R. D.|title=The Behavior Guide to African Mammals: Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates|year=2004|publisher=University of California Press|location=Berkeley, USA|isbn=978-0-520-08085-0|pages=133–42|edition=4th}}</ref> Often the mortality rate of male juveniles is high, as they have to face the aggression of territorial adult males and are also deprived of good forage by them.<ref name=kingdon/> The lifespan is 11 to 20 years in the wild and up to 19 years in captivity.<ref name=awf/> |

|||

==Habitat== |

|||

Hartebeest inhabit dry savannas, open plains and wooded grasslands,<ref name=nowak/> often moving into more arid places after rainfall. They are more tolerant of wooded areas than other Alcelaphini, and are often found on the edge of woodlands.<ref name=awf/> They have been reported from altitudes on [[Mount Kenya]] up to {{convert|4000|m|ft|abbr=on}}.<ref name=iucn/> The red hartebeest is known to move across large areas, and females roam home ranges of over {{convert|1000|sqkm|sqmi|abbr=on}}, with male territories {{convert|200|sqkm|sqmi|abbr=on}} in size.<ref name=mills>{{cite book|last1=Mills|first1=G.|last2=Hes|first2=L.|title=The Complete Book of Southern African Mammals|year=1997|publisher=Struik Publishers|location=Cape Town, South Africa|isbn=978-0-947430-55-9|page=255}}</ref> Females in the [[Nairobi National Park]] (Kenya) have individual home ranges stretching over {{convert|3.7|–|5.5|sqkm|sqmi|abbr=on}}, which are not particularly associated with any one female group. Average female home ranges are large enough to include 20 to 30 male territories.<ref name=Macdonald/> |

|||

==Status and conservation== |

|||

[[File:Hartebeests Serengeti.jpg|thumb|Coke's hartebeest in Serengeti National Park, Tanzania]] |

|||

[[File:2011-Red-Hartebeest.jpg|thumbnail|Red hartebeest in Etosha National Park, Namibia]] |

|||

[[File:Alcelaphus buselaphus herd.png|thumbnail|Western hartebeest in Pendjari National Park, Benin]] |

|||

Each hartebeest subspecies is listed under a different conservation status by the IUCN. The species as a whole is classified as [[Least Concern]] by the IUCN.<ref name=iucn/> The hartebeest is extinct in Algeria, Egypt, Lesotho, Libya, Morocco, Somalia, and Tunisia.<ref name=iucn/> |

|||

* The '''Bubal hartebeest''' has been declared [[extinct]] since 1994.<ref name=bubal/> German explorer [[Heinrich Barth]], in his works of 1857, cites firearms and European intrusion among the reasons for the decrease in its numbers.<ref name=yadav>{{cite book|last=Yadav|first=P. R.|title=Vanishing and Endangered Species|year=2004|publisher=Discovery Publishing House|location=New Delhi, India|isbn=978-81-7141-776-6|pages=139–40}}</ref> It was extinct in [[Tunisia]] by the late 19th century.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Mallon|first1=D. P.|last2=Kingswood|first2=S. C.|title=Antelopes: North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia|year=2001|publisher=IUCN|location=Gland, Switzerland|isbn=978-2-8317-0594-1}}</ref> The last individual was shot in [[Missour]] ([[Algeria]]) in 1925.<ref name=harper>{{cite book|last1=Harper|first1=F.|title=Extinct and Vanishing Mammals of the Old World|date=1945|publisher=American Committee for International Wildlife Protection|location=New York, USA|pages=642–8|url=http://www.archive.org/stream/extinctvanishing00harprich#page/643/mode/1up}}</ref> |

|||

*'''Coke's hartebeest''' is listed as Least Concern. This species has been greatly affected by habitat destruction, and about 42,000 Coke's hartebeest occur today in [[Mara Region|Mara]], [[Serengeti National Park]], and [[Tarangire National Park]] in Tanzania and [[Tsavo East National Park]] in Kenya. The population is decreasing, and 70% of the population lives in protected areas.<ref name=coke>{{IUCN2008 |assessors=IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group |year=2008 |title=Alcelaphus buselaphus cokii|id=815 |downloaded=23 February 2016}}</ref> |

|||

*The '''Lelwel hartebeest''' is listed as Endangered, and numbers have declined greatly since the 1980s, when its population was over 285,000. It was formerly distributed mainly in the Central African Republic, Ethiopia, northern and northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo and southern Sudan.<ref name=east/> Fewer than 70,000 individuals are left.<ref name=lelwel/> Most of the population nowadays is found in Chad in the [[Salamat Region|Salamat]] region and the [[Zakouma National Park]] (Chad), the National Park population benefiting from improved protection and seeing an increase in population since the 1980s; [[Manovo-Gounda St. Floris National Park]] and [[Bamingui-Bangoran National Park and Biosphere Reserve]] in the Central African Republic, where the populations have been falling; [[Rumanyika Orugundu Game Reserve]] and [[Ibanda Game Reserve]] in Tanzania; and [[Murchison Falls National Park]] in [[Uganda]].<ref name=east/> |

|||

*'''Lichtenstein's hartebeest''' is listed as Least Concern, and occurs in protected areas such as the [[Selous Game Reserve]] and in the wild in southern and western Tanzania and Zambia.<ref name=lh>{{IUCN2008 |assessors=IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group |year=2008 |title=Alcelaphus buselaphus lichtensteinii|id=812 |downloaded=23 April 2013}}</ref> |

|||

* The '''red hartebeest''' is listed as Least Concern. It is the most widespread, with increasing numbers after its reintroduction into protected and private areas. However, it has been extinct in [[Lesotho]] since the twentieth century.<ref name=east/> Its population is estimated to be over 130,000 (as of 2008),<ref name=caama/> mostly in southern Africa.<ref name=mills/> In Namibia, the largest population occurs in the [[Etosha National Park]]. A reintroduced population is flourishing in the [[Malolotja Nature Reserve]] ([[Swaziland]]), outside its range. However, numbers have seen a sharp fall in southwestern Botswana.<ref name=east/> |

|||

*The '''Tora hartebeest''' is listed as [[Critically Endangered]]; the IUCN has ascertained that fewer than 250 mature individuals survive as of 2008. They are possibly extinct in Sudan due to excessive hunting and agricultural expansion, but may still exist in smaller numbers in Eritrea and Ethiopia.<ref name=tora>{{IUCN2008 |assessors=IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group |year=2008 |title=Alcelaphus buselaphus tora|id=810 |downloaded=23 January 2013}}</ref> There have been unconfirmed reports of sightings by locals of the Tora hartebeest southeast of the [[Dinder National Park]], from where it had disappeared before 1960.<ref name=east/> |

|||

*'''Swayne's hartebeest''' is listed as [[Endangered]], and is close to being [[Critically Endangered]]. The total population in 2008 was less than 600, of which the mature specimens numbered within 250. It is confined to four major protected areas: the [[Senkele Wildlife Sanctuary]], [[Nechisar National Park]], [[Awash National Park]] and [[Mazie National Park]].<ref name=swayne>{{IUCN2008 |assessors=IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group |year=2008 |title=Alcelaphus buselaphus swaynei|id=809 |downloaded=24 April 2013}}</ref> The hartebeest in Senkele have to compete with the livestock of the [[Oromo people]].<ref name=lewis/> A study in the Nechisar National Park during 2009 and 2010 found a considerable increase in the livestock of the Oromos (49.9% and 56.5% increase during 2006 and 2010, respectively), illegal resource exploitation, and habitat loss as major threats to the Swayne's hartebeest populations there.<ref name=datiko>{{cite journal|last=Datiko|first=D.|last2=Bekele|first2= A.|title=Population status and human impact on the endangered Swayne's hartebeest (''Alcelaphus buselaphus swaynei'') in Nechisar Plains, Nechisar National Park, Ethiopia|journal=African Journal of Ecology|year=2011|volume=49|issue=3|pages=311–9|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2028.2011.01266.x}}</ref> |

|||

*The '''western hartebeest''' is listed as [[Near Threatened]].<ref name=major>{{IUCN2008 |assessors=IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group |year=2008 |title=Alcelaphus buselaphus major|id=817 |downloaded=23 January 2013}}</ref> It has been eliminated from most of its range, including the southwestern savannas and [[Boucle du Baoulé National Park]] in Mali; southwestern Niger; southern Senegal; Gambia; [[Ivory Coast]]; [[Burkina Faso]]. Small populations survive in [[Bafing National Park]] and the area bounded by [[Bamako]], [[Bougouni]] and [[Sikasso]] in Mali; [[Tamou Reserve]] in Niger; [[Niokolo-Koba National Park]] in Senegal; [[Comoé National Park]] in Ivory Coast; [[Diefoula]] forest and [[Nazinga Game Ranch]] in Burkina Faso; [[Pendjari National Park]] in Benin; and [[Bouba Njida National Park|Bouba Njida]], [[Bénoué National Park|Bénoué]], and [[Faro National Park|Faro]] National Parks in Cameroon.<ref name=east/> |

|||

==Relationship with humans== |

|||

Hartebeest are popular [[game animal|game]] and [[Trophy hunting|trophy]] animals as they are prominently visible and hence easy to hunt.<ref name=kingdon/><ref name=awf/> Pictorial as well as [[epigraphy|epigraph]]ic evidence from [[Egypt]] suggests that in the [[Upper Palaeolithic|Upper Palaeolithic age]], Egyptians hunted hartebeest and domesticated them. The hartebeest was a prominent source of meat,<ref name="neer">{{cite book|last1=Van Neer|first1=W.|last2=Linseele|first2=V.|last3=Friedman|first3=R. F.|editor1-last= Hendrickx|editor1-first=S.|editor2-last=Friedman|editor2-first=R|editor3-last=Ciałowicz|editor3-first=K.|editor4-last=Chłodnicki|editor4-first=M.|chapter=Animal burials and food offerings at the elite cemetery HK6 of Hierakonpolis|title=Egypt at its Origins: Studies in Memory of Barbara Adams|series=Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta|volume=138|location=Leuven, Belgium|publisher= Peeters Publishers|page=111|url=https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Z169xREnHQwC&oi=fnd&pg=PA67&dq=+Animal+Burials+and+Food+Offerings+at+the+Elite+Cemetery+HK6+of+Hierakonpolis&ots=DpS5v7k0bW&sig=wNgE7xUw0OXVv4QEOEOpaMmxlis#v=onepage&q=Animal%20Burials%20and%20Food%20Offerings%20at%20the%20Elite%20Cemetery%20HK6%20of%20Hierakonpolis&f=false}}</ref> but its economic significance was lower than that of gazelles and other desert species.<ref name=heckel/> However, from the beginning of the Neolithic age, hunting became less common and consequently the remains of the hartebeest from this period in Egypt, where it is now extinct, are rare.<ref name=neer/> |

|||

In a study on the effect of place and sex on carcass characteristics, the average carcass weight of the male red hartebeest was {{convert|79.3|kg|lb|abbr=on}} and that of females was {{convert|56|kg|lb|abbr=on}}. The meat of the animals from Qua-Qua region had the highest [[lipid]] content—{{convert|1.3|g|oz|abbr=on}} per {{convert|100|g|oz|abbr=on}} of meat. Negligible differences were found in the concentrations of individual [[fatty acid]]s, [[amino acid]]s, and [[dietary mineral|mineral]]s. The study considered hartebeest meat to be healthy, as the ratio of [[Polyunsaturated fatty acid|polyunsaturated]] to [[saturated fatty acid]]s was 0.78, slightly more than the recommended 0.7.<ref name=hoffman>{{cite journal|last1=Hoffman|first1=L. C.|last2=Smit |first2=K. |last3= Muller |first3= N. |title=Chemical characteristics of red hartebeest (''Alcelaphus buselaphus caama'') meat|journal=South African Journal of Animal Science|year=2010|volume=40|issue=3|pages=221–8|doi=10.4314/sajas.v40i3.6}}</ref> |

|||

{{Przypisy}} |

|||

Wersja z 13:33, 8 maj 2016

| Alcelaphus buselaphus[1] | |||

| (Pallas, 1766) | |||

| |||

| Systematyka | |||

| Domena | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Królestwo | |||

| Gromada | |||

| Podgromada | |||

| Infragromada | |||

| Rząd | |||

| Rodzina | |||

| Podrodzina | |||

| Rodzaj | |||

| Gatunek |

bawolec krowi | ||

| Synonimy | |||

| |||

| Podgatunki | |||

| |||

| Kategoria zagrożenia (CKGZ)[2] | |||

| |||

| Zasięg występowania | |||

| |||

The hartebeest (Szablon:Ipa-en), also known as kongoni, is an African antelope, first described by the German zoologist Peter Simon Pallas in 1766. Eight subspecies have been described, including two sometimes considered to be independent species. A large antelope, the hartebeest stands just over 1 m (3,3 ft) at the shoulder, and has a typical head-and-body length of 200 do 250 cm (79 do 98 in). The weight ranges from 100 do 200 kg (220 do 440 lb). It has a particularly elongated forehead and oddly shaped horns, short neck, and pointed ears. Its legs, which often have black markings, are unusually long. The coat is generally short and shiny. Coat colour varies by the subspecies, from the sandy brown of the western hartebeest to the chocolate brown of the Swayne's hartebeest. Both sexes of all subspecies have horns, with those of females being more slender. Horns can reach lengths of 45–70 cm (18–28 in). Apart from its long face, the large chest and the sharply sloping back differentiate the hartebeest from other antelopes.

Gregarious animals, hartebeest form herds of 20 to 300 individuals. They are very alert and non-aggressive. They are primarily grazers, with their diets consisting mainly of grasses. Mating in hartebeest takes place throughout the year with one or two peaks, and depends upon the subspecies and local factors. Both males and females reach sexual maturity at one to two years of age. Gestation is eight to nine months long, after which a single calf is born. Births usually peak in the dry season. The lifespan is 11 to 20 years in the wild and up to 19 years in captivity.

Inhabiting dry savannas and wooded grasslands, hartebeest often move to more arid places after rainfall. They have been reported from altitudes on Mount Kenya up to 4 000 m (13 000 ft). The hartebeest was formerly widespread in Africa, but populations have undergone drastic decline due to habitat destruction, hunting, human settlement, and competition with livestock for food. Each of the eight subspecies of the hartebeest has a different conservation status. The Bubal hartebeest was declared extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 1994. While the populations of the red hartebeest are on the rise, those of the Tora hartebeest, already Critically Endangered, are falling. The hartebeest is extinct in Algeria, Egypt, Lesotho, Libya, Morocco, Somalia, and Tunisia; but has been introduced into Swaziland and Zimbabwe. It is a popular game animal due to its highly regarded meat.

Etymology

The vernacular name "hartebeest" (Szablon:Ipa-en)[3] could have originated from the obsolete Afrikaans word hertebeest,[4] while another supposed origin of the name is from the combination of the Dutch words hert (deer) and beest (beast).[3] The name was given by the Boers, based on the resemblance of the antelope to deer.[5] The first use of the word "hartebeest" in South African literature was in Dutch colonial administrator Jan van Riebeeck's journal Daghregister in 1660. He wrote: "Meester Pieter ein hart-beest geschooten hadde (Master Pieter [van Meerhoff] had shot one hartebeest)".[6] Another name for the hartebeest is kongoni,[7] a Swahili word.[8] Kongoni is often used to refer in particular to one of its subspecies—Coke's hartebeest.[9]

Taxonomy

The scientific name of the hartebeest is Alcelaphus buselaphus. First described by German zoologist Peter Simon Pallas in 1766, it is classified in the genus Alcelaphus and placed in the family Bovidae.[10] In 1979, palaeontologist Elisabeth Vrba supported Sigmoceros as a separate genus for Lichtenstein's hartebeest, a kind of hartebeest, as she assumed it was related to Connochaetes (wildebeest).[11][12] She had analysed the skull characters of living and extinct species of antelope to make a cladogram, and argued that a wide skull linked Lichtenstein's hartebeest with Connochaetes.[13] However, this finding was not replicated by Alan W. Gentry of the Natural History Museum, who classified it as an independent species of Alcelaphus.[14] Zoologists such as Jonathan Kingdon and Theodor Haltenorth considered it to be a subspecies of A. buselaphus.[10] Vrba dissolved the new genus in 1997 after reconsideration.[15] An MtDNA analysis could find no evidence to support a separate genus for Lichtenstein's hartebeest. It also showed the tribe Alcelaphini to be monophyletic, and discovered close affinity between the Alcelaphus and the sassabies (genus Damaliscus)—both genetically and morphologically.[16]

Subspecies

Eight subspecies are identified, of which two – A. b. caama and A. b. lichtensteinii – have been considered to be independent species. However, a 1999 genetic study by P. Arctander of the University of Copenhagen and colleagues, which sampled the control region of the mitochondrial DNA, found that these two formed a clade within A. buselaphus, and that recognising these as species would render A. buselaphus paraphyletic (an unnatural grouping). The same study found A. b. major to be the most divergent, having branched off before the lineage split to give a combined caama/lichtensteinii lineage and another that gave rise to the remaining extant subspecies.[17] Conversely a 2001 phylogenetic study, based on D–loop and cytochrome b analysis by Øystein Flagstad (of the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Trondheim) and colleagues, found that the southern lineage of A. b. caama and A. lichtensteinii diverged earliest.[12] Analysis of skull structure supports partition into three major divisions: A. b. buselaphus division (nominate, also including A. b. major division), A. b. tora division (also including A. b. cokii and A. b. swaynei) and A. b. lelwel division.[10] Another analysis of cytochrome b and D-loop sequence data shows a notable affinity between the A. b. lelwel and A. b. tora divisions.[18]

The eight subspecies, including the two controversial ones, are:[2][19]

- † A. b. buselaphus (Pallas, 1766) : Known as the Bubal hartebeest or northern hartebeest. Formerly occurred across northern Africa, from Morocco to Egypt. It was exterminated by the 1920s.[20] It was declared extinct in 1994 by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).[21][22]

- A. b. caama (Saint-Hilaire, 1803) : Known as the red hartebeest or Cape hartebeest. Formerly occurred in southern Angola; northern and eastern savannahs of Namibia; central, southern and southwestern Botswana; Northern Cape, Eastern Cape, Western Cape, Free State, Northwest and Gauteng provinces and western KwaZulu-Natal of South Africa. Presently has been eliminated from all these areas except Northern Cape, central and southwestern Botswana and Namibia. Major re-introductions have taken place in these countries.[20] The population of this hartebeest is on the rise.[23]

- A. b. cokii (Günther, 1884): Known as Coke's hartebeest or kongoni. Native to and confined within Kenya and northern Tanzania.[20]

- A. b. lelwel (Heuglin, 1877) : Known as the Lelwel hartebeest. Formerly found in northern and northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo; southeastern and southwestern Sudan; and the northwestern extreme of Tanzania.[20] Drastic population decrease since the 1980s has confined most individuals to protected areas inside and outside its range.[24]

- A. b. lichtensteinii (Peters, 1849) : Known as Lichtenstein's hartebeest. Inhabits the miombo woodlands of eastern and southern Africa.[25] It is native to Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.[26]

- A. b. major (Blyth, 1869) : Known as the western hartebeest. Formerly occurred widely in Mali, Niger, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Nigeria, southwestern Chad, Cameroon, western Central African Republic and Benin. Nowadays it occurs in much lower numbers mainly in protected areas of these countries. It is probably extinct in Gambia.[20]

- A. b. swaynei (Sclater, 1892) : Known as Swayne's hartebeest. Restricted to the southern Rift Valley in Ethiopia. It formerly occurred throughout the Rift Valley, and its range extended eastward into northwestern Somalia. It has disappeared from Somalia by 1930.[20] Its populations are very low and on the decline.[27]

- A. b. tora (Gray, 1873) : Known as the Tora hartebeest. Formerly occurred in northwestern Ethiopia and western and southwestern Eritrea.[28] Its present status is unclear, though locals have reported small numbers from these areas.[20]

Genetics and hybrids

In 2000, a study scrutinised two major populations of the Swayne's hartebeest, from the Senkele Wildlife Sanctuary and the Nechisar National Park, for mitochondrial (D-loop) and nuclear (microsatellite) variability in an attempt to estimate the levels of genetic variation between the populations and within the subspecies. The results showed a remarkable differentiation between the two populations; that from the Senkele Wildlife Sanctuary showed more genetic diversity than the one from the Nechisar National Park. Another revelation was that the translocation of the individuals from the Senkele Wildlife Sanctuary in 1974 had not made a significant contribution to the gene pool of the Nechisar National Park. Additionally, the Swayne hartebeest populations were compared with a large red hartebeest population, and both subspecies were found to have a high degree of genetic variation. The study advocated in situ conservation of the Swayne's hartebeest and a renewed attempt at its translocation in order to conserve genetic diversity and increase its population size in both the protected areas.[18]

The diploid number of chromosomes in the hartebeest is 40. Hybrids are usually reported from areas where ranges of two subspecies overlap.[7] Hybrids between the Lelwel and Tora hartebeest have been reported in eastern Sudan and western Ethiopia, in a stretch southward from the Blue Nile to about 9° N latitude.[29] A study proved a male hybrid of the red hartebeest and the blesbok (Damaliscus pygargus) to be sterile. Sterility of the hybrid was attributed to difficulties in segregation during meiosis, indicated by azoospermia and a low number of germ cells in its seminiferous tubules.[30]

There are three common cross-breeds between the subspecies:

- Alcelaphus lelwel x cokii: Known as the Kenya Highland hartebeest or the Laikipia hartebeest. It is a cross between the Lelwel and Coke's hartebeest.[31] This hybrid is lighter in colour and larger than Coke's hartebeest. It is a light buff with reddish-tawny upper parts, and the head is longer than in Coke's hartebeest. Both sexes have horns, which are heavier as well as longer than those of the parents. It was formerly distributed throughout the western Kenyan highlands, between Lake Victoria and Mount Kenya, but is now believed to be restricted to the Lambwe Valley (south-west Kenya) and Laikipia and nearby regions of west-central Kenya.[32][33]

- Alcelaphus lelwel x swaynei : Also known as the Neumann's hartebeest, named after traveller and hunter Arthur Henry Neumann.[34] This is considered to be a cross between the Lelwel hartebeest and Swayne's hartebeest.[31] The face is longer than that of the Swayne's hartebeest. The colour of the coat is a golden brown, paler towards the underparts. The chin has a hint of black and the tail ends in a black tuft. Both sexes have longer horns than the Swayne's hartebeest. The horns grow in a wide "V" shape, unlike the wide bracket shape of Swayne's hartebeest and the narrow "V" of Lelwel hartebeest, curving backward and slightly inward. It occurs in Ethiopia, in a small area to the east of Omo River and north of Lake Turkana, stretching north-east of Lake Chew Bahir to near Lake Chamo.[35]

- The Jackson's hartebeest does not have a clear taxonomic status. It is regarded as a hybrid between the Lelwel and Coke's hartebeest. The African Antelope Database (1998) treats it as synonymous to the Lelwel hartebeest.[20] From Lake Baringo to Mount Kenya, the Jackson's hartebeest significantly resembles the Lelwel hartebeest, whereas from Lake Victoria to the southern part of the Rift Valley it tends to be more like the Coke's hartebeest.[34]

Evolution