Wikiprojekt:Tłumaczenie artykułów/Niemcy

Szablon:About Szablon:Pp-semi-protected Szablon:Pp-move-indef Szablon:Infobox country

Niemcy (Szablon:IPAc-en; (niem.) Deutschland), officially the Republika Federalna Niemiec ((niem.) Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Szablon:IPA-de)[1], is a federal parliamentary republic in western-central Europe. The country consists of 16 states, and its capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357 021 km2 (137 847 sq mi) and has a largely temperate seasonal climate. With 80.3 million inhabitants, it is the most populous member state in the European Union. Germany is the major economic and political power of the European continent and a historic leader in many theoretical and technical fields.

A region named Germania, inhabited by several Germanic peoples, was documented before AD 100. During the Migration Period, the Germanic tribes expanded southward and established successor kingdoms throughout much of Europe. Beginning in the 10th century, German territories formed a central part of the Holy Roman Empire[2] During the 16th century, northern German regions became the centre of the Protestant Reformation while southern (most notably Bavaria) and western parts remained dominated by Roman Catholic denominations, with the two factions clashing in the Thirty Years' War, marking the beginning of the Catholic–Protestant divide that has characterized German society ever since[3]. Occupied during the Napoleonic Wars, the rise of Pan-Germanism inside the German Confederation resulted in the unification of most of the German states in 1871 into the German Empire, which was dominated by Prussia.

After the German Revolution of 1918–1919 and the subsequent military surrender in World War I, the Empire was replaced by the parliamentary Weimar Republic in 1918, and some of its territory partitioned in the Treaty of Versailles. Despite its lead in many scientific and artistic fields at this time, amidst the Great Depression, the Third Reich was established in 1933. The latter period was marked by fascism and World War II. After 1945, Germany was divided by allied occupation, and evolved into two states, East Germany and West Germany. In 1990, the country was reunified.

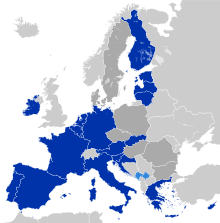

Germany was a founding member of the European Community in 1957, which became the EU in 1993. It is part of the Schengen Area, and since 1999, a member of the euro area. Germany is a great power and member of the United Nations, NATO, the G8, the G20, the OECD and the Council of Europe, and took a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council for the 2011–2012 term.

Germany has the world’s fourth-largest economy by nominal GDP and the fifth-largest by purchasing power parity. Subsequently, it is the second-largest exporter and third-largest importer of goods. The country has developed a very high standard of living and features a comprehensive system of social security, which includes the world’s oldest universal health care system. Germany has been the home of many influential philosophers, music composers, scientists and inventors, and is known for its rich cultural and political history.

Etymology[edytuj | edytuj kod]

The English word Germany derives from the Latin Germania, which came into use after Julius Caesar adopted it for the peoples east of the Rhine.[4] The German term Deutschland (originally diutisciu land, "the German lands") is derived from deutsch, descended from Old High German diutisc "popular" (i.e. belonging to the diot or diota "people"), originally used to distinguish the language of the common people from Latin and its Romance descendants. This in turn descends from Proto-Germanic *þiudiskaz "popular" (see also the Latinised form Theodiscus), derived from *þeudō, descended from Proto-Indo-European *tewtéh₂- "people".[5]

Historia[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Plemiona germańskie[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Plemiona germańskie wyodrębniły się prawdopodobnie w Epoce Brązu lub Żelaza. Z południowej Skandynawii i północnych Niemiec, od I wieku p.n.e. wędrowali na południe, wschód i zachód, stykając się z plemionami celtyckimi, żyjącymi na terenie Galii, a także ludami irańskimi, Bałtami, oraz Słowianami w Środkowej i Wschodniej Europie[6]. Za sprawą Oktawiana Augusta, rzymski dowódca Warus rozpoczął podbój Germanii (obszaru ciągnącego się od Renu do gór Ural). W 9 r. n.e., trzy rzymskie legiony zostały pokonane podczas bitwy w Lesie Teutoburskim przez Cherusków pod wodzą Arminiusa. Do roku 100, kiedy Tacyt napisał Germanię, plemiona germańskie osiedliły się wzdłuż Renu i Dunaju (Limes Górnogermańsko-Retycki), zajmując większość terenu dzisiejszych Niemiec. Austria, południowa Bawaria oraz zachodnia Nadrenia były jednak rzyskimi prowincjami[7].

W trzecim wieku pojawiły się kolejne duże plemiona germańskie: Alamanowie, Frankowie, Chattowie, Sasi, Fryzowie oraz Turyngowie. Około 260 r., Germanie wkroczyli na tereny kontrolowane przez Cesarstwo Rzymskie[8]. Po inwazji Hunów w 375 r. oraz podupadania Rzymu od 395 r., plemiona germańskie dalej migrowały na południowy wschód. Większe z nich zaczęły dominować nad słabszymi. Rozległe obszary zajmowali Frankowie, a tereny północne należały do Sasów[7].

Święte Cesarstwo Rzymskie[edytuj | edytuj kod]

25 grudnia 800 r., król Franków Karol Wielki został ukoronowany cesarzem i stworzył Imperium Karolińskie, które zostało podzielone w 843 r., na podstawie Traktatu w Verdun. Święte Cesarstwo Rzymskie powstało ze wschodniej części podzielonego obszaru. Jego terytorium rozciągało się od rzeki Eider na północy do wybrzeży Morza Śródziemnego na południu[7]. Podczas panowania władców z dynastii Ludolfingów w latach 919–1024, kilka ważniejszych księstw zostało połączonych, a król niemiecki został ukoronowany na Świętego Cesarza Rzymskiego w 962 r. Święte Cesarstwo Rzymskie wchłonęło północną Italię i Burgundię podczas rządów dynastii salickiej (1024–1125), lecz cesarze utracili znaczną część swojej potęgi podczas sporu o inwestyturę.

W okresie panowania Hohenstaufów (1138–1254), niemieccy książęta rozszerzyli swoje wpływy dalej na wschód i południe, na ziemie należące do Słowian, rozpoczynając osadnictwo na tych i leżących jeszcze dalej na wschód terenach. Północne miasta niemieckie rozwijały się jako członkowie Hanzy[7]. W późniejszym okresie liczba ludności kraju zdecydowanie zmniejszyła się z powodu Wielkiego głodu w latach 1315–1317, a następnie Czarnej Śmierci w latach 1348–1350[9]. Złota Bulla z 1356 r. wprowadziła podstawową konstytucję kraju i wprowadziła w cesarstwie elekcję króla przez siedmiu elektorów[7].

Martin Luter opublikował 95 tez w 1517 r. w Wittenberdze, rzucajac tym samym wyzwanie Kościołowi katolickiemu i rozpoczynając reformację. Kościół Luterański stał się oficjalną religią w wielu niemieckich księstwach do roku 1530. Spór religijny doprowadził do wojny trzydziestoletniej (1618–1648), w ciągu której populacji regionu spadła o 30%[10]. Pokój westfalski w 1648 r. zakończyło wojny religijne w Niemczech, jednak kraj pozostał podzielony na wiele małych państewek[11]. W XVIII wieku, Święte Cesarstwo Rzymskie składało się z około 1800 takich terytoriów[12].

Od 1740 r., spory pomiędzy austriacką monarchią Habsburgów oraz Prusami zdominował niemiecką historię. W 1806 r., imperium zostało rozwiązane w rezultacie wojen napoleońskich[7].

Związek Niemiecki i Cesarstwo[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Podczas upadku Napoleona, Kongres wiedeński w 1814 stworzył Związek Niemiecki (Deutscher Bund), luźną ligę 39 krajów. Niezgoda z europejską restauracją monarchów, spowodowała zwiększenie ruchów liberalnych, co spowodowało wprowadzenie nowych represji przez austriackiego kanclerza Klemensa von Metternicha. Niemiecki Związek Celny, unia celna, podtrzymywała ekonomiczną równość wszystkich państw niemieckich[13]. Nacjonalizm i liberalne idee Rewolucji Francuskiej zdobyły rosnące poparcie Niemców, głównie młodych. W świetle wiosny ludów, która zdestabilizowała francuską republikę, intelektualiści i inni obywatele rozpoczęli rewolucję. Król prus, Fryderyk Wilhelm IV otrzymał ofertę zostania cesarzem, ale z ograniczoną władzą, co sprawiło, że zrezygnował z korony i zaproponował wprowadzenie konstytucji, doprowadzając do czasowego niepowodzenia ruchu nacjonalistycznego[14].

Konflikt pomiędzy królem Prus Wilhelmem I Hohenzollernem i coraz bardziej liberalnym parlamentem wybuchł w związku z reformami wojskowymi w 1862 r. Król mianował nowego kanclerza, Otto von Bismarcka[14]. Doprowadził on do wojny z Danią w 1864 r. Pruskie zwycięstwo w wojnie z Austrią w 1866 r. umożliwiło utworzenie Związku Północnoniemieckiego (Norddeutscher Bund) i wykluczenia Austrii, dotąd jednego z państw niemieckich, z federacji. Po pokonaniu przez Prusy Francji podczas wojny w 1970 r., w 1871 r. proklamowano Cesarstwo Niemieckie w Wersalu, które połączyło wszystkie państewka niemieckie poza Austrią.

Prusy, które zajmowały ok. 2/3 powierzchni nowego państwa, zdominowały je. Pruscy królowie z dynastii Hohenzollernów przybrali tytuł cesarski, a Berlin stał się jego stolicą[14]. W kolejnych latach, dzięki polityce zagranicznej Bismarck jako kanclerz Niemiec pod rozkazami cesarza, zapewnił państwu silną pozycję na arenie międzynarodowej poprzez fałszowanie przymierzy, odosabnienie Francji w sprawach dyplomatycznych i unikanie wojen. Za panowania Wilhelma II Hohenzollerna, Niemcy zaczęły stawać się państwem imperialistycznym, co prowadziło do konfliktów z sąsiednimi krajami. W rezultacie Konferencji berlińskiej w 1884 r. Niemcy zażądały przyznania wielu kolonii, np.: Niemieckiej Afryki Wschodniej, Niemieckiej Afryki Południowo-Zachodniej, Togo, oraz Kamerunu[15]. Większość przymierzy, do których dawniej przystąpiły Niemcy nie zostało odnowionych, a w nowych wykluczono państwo[7].

Zamach w Sarajewie na Franciszka Ferdynanda Habsburga 28 czerwca 1914 r. wywołał I wojnę światową[16]. Niemcy, jako część państw centralnych, ucierpiały poprzez porażkę z Aliantami podczas jednego z najkrwawszych konfliktów w historii. Około 2 miliony niemieckich żołnierzy zginęło podczas wojny. Rewolucja listopadowa wybuchła w listopadzie 1918 r., a król Wilhelm II i książęta abdykowali. Rozejm w Compiègne zakończył I wojnę światową 11 listopada, a Niemcy zostały zmuszone do podpisania pokoju wersalskiego w czerwcu 1919 r. Pokój został odebrany w Niemczech jako poniżająca kontynuacja konfliktu, i jest często wymieniana jako jedna z przyczyn rozwoju nazizmu[17].

Republika Weimarska i nazizm[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Na początku niemieckiej rewolucji w listopadzie 1918 r., Niemcy stały się republiką. Walka o władzę toczyła się jednak dalej, z radykalnie-lewicowymi komunistami, którzy przejęli władzę w Bawarii. Rewolucja chyliła się ku końcowi 11 sierpnia 1919 r., kiedy demokratyczna konstytucja weimarska została zatwierdzona przez prezydenta Friedricha Eberta[7]. Nastąpił wtedy okres rozwoju kulturalnego i ekonomicznego państwa, nazywany „złotymi latami dwudziestymi”, czyli Goldene Zwanziger. W 1929 r. nastąpił jednak wielki kryzys. Surowe warunki pokoju dyktowane przez traktat wersalski, a także długi czas niestabilnych rządów, Niemcy coraz rzadziej identyfikowali się z rządem. Sytuację zaostrzała Legenda o ciosie w plecy, czyli przekonanie, iż winę za przegranie I wojny światowej ponoszą cywile, którzy niewystarczająco wsparli wojsko. Rząd został oskarżony o zdradę państwa poprzez podpisanie traktatu wersalskiego.

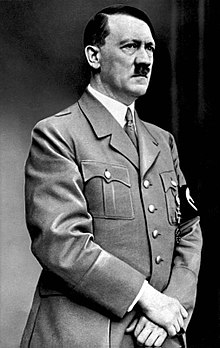

Do 1932 r. Komunistyczna Partia Niemiec oraz Narodowosocjalistyczna Niemiecka Partia Robotników kontrolowały większość parlamentu, podsycając niezadowolenie z rządu. Po serii nieudanych prób utworzenia rządu, prezydent Paul von Hindenburg mianował Adolfa Hitlera kanclerzem Niemiec. Miało to miejsce 20 stycznia 1933 r[7]. 27 lutego 1933 doszło do pożaru Reichstagu i w konsekwencji zniesienia wielu praw obywateli. Wkrótce umożliwiono także wprowadzanie przez rząd ustaw niezgodnych z konstytucją. Jedynie Socjaldemokratyczna Partia Niemiec głosowała przeciwko, podczas gdy posłowie Komunistycznej Partii Niemiec byli już uwięzieni[18][19]. Poprzez używanie swojej władzy w celu zniszczenia jakiegokolwiek, realnego lub domniemanego, oporu, Hitler stworzył scentralizowane państwo totalitarne w ciągu miesięcy. Gospodarka została odbudowana, skupiała się jednak odtąd głównie na zbrojeniu militarnym[20].

W 1935 r. Niemcy odzyskały kontrolę nad krainą Saara, a w 1936 r. nad Nadrenią, które zostały utracone na mocy traktatu wersalskiego[7]. W 1938 r. przyłączono do państwa Austrię, a w 1939 pod niemiecką kontrolą znalazła się Czechosłowacja. Kampania wrześniowa, czyli inwazja na Polskę, została przygotowana na podstawie Paktu Ribbentrop-Mołotow i Operacji Himmler. 1 września 1939 roku niemiecki Wehrmacht przeprowadziłblitzkrieg na Polskę, która szybko została zajęta przez III Rzeszę i sowiecką Armię Czerwoną. Wielka Brytania i Francji wypowiedziały Niemcom wojnę, co było oznaką rozpoczynającej się II wojny światowej[7]. W trakcie rozwoju konfliktu, Niemcy i ich sprzymierzeńcy szybko zdobyły kontrolę w większości Europy Kontynentalnej i Północnej Afryce. Planowano także opanowanie Wielkiej Brytanii, zakończyło się to jednak niepowodzeniem. 22 czerwca 1941 r., Niemcy złamały patk Ribbentrop-Mołotow i zaatakowały Związek Radziecki. Japonia zaatakowała Pearl Harbor, zo spowodowało przyłączenie się do konfliktu Stanów Zjednoczonych. Bitwa pod Stalingradem zmusiła Niemcy do odwrotu na froncie wschodnim[7].

We wrześniu 1943 r., sprzymierzeniec III Rzeszy, Włochy, poddały się, a niemieckie oddziały musiały bronić dodatkowego frontu we Włoszech. Lądowanie w Normandii otworzyło Front Zachodni, podczas gdy siły aliantów postępowały w głąb niemieckiego terytorium. 8 maja 1945 r. siły III Rzeszy poddały się po zdobyciu przez Armię Czerwoną Berlina[21].

III Rzesza często stosowała w swoich poczynaniach holokaust. Reżim powołał policję, która usuwała mniejszości narodowe i grupy etniczne z danych terenów. Miliony ludzi zostało zabitych w tym okresie, w tym wielu Żydów, Romów, Rosjan, niepełnosprawnych, Świadków Jehowy, homoseksualistów, a także członków opozycji[22]. W czasie wojny III Rzesza straciła szacunkowo 5,3 miliona żołnierzy[23] i miliony cywilów[24], a także dużą część swego dawnego terytorium[25].

Niemcy Wschodnie i Zachodnie[edytuj | edytuj kod]

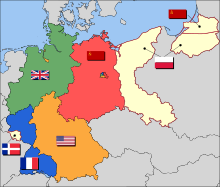

Po złożeniu broni przez Niemcy, terytorium państwa oraz jego stolica zostały podzielone przez aliantów na cztery strefy okupacyjne. W sumie, zmiany te zaakceptowało 6,5 miliona Niemców, wysiedlonych ze wschodnich terenów[26]. Część zachodnia, kontrolowana przez Francję, Wielką Brytanię oraz Stany Zjednoczone, została połaczona 23 maja 1949 r. tworząc Republikę Federalną Niemiec (Bundesrepublik Deutschland), a 7 października 1949 roku, strefa radziecka stała się Niemiecką Republikę Demokratyczną (Deutsche Demokratische Republik). Państwa te były nieformalnie znane pod nazwami Niemcy Wschodnie i Niemcy Zachodnie. Niemcy Wschodnie wybrały na swoją stolicę Berlin, podczas gdy siedzibą rządu Niemiec Zachodnich stało się Bonn[27].

Niemcy Zachodnie, stworzone jako republika fedralna ze społeczną gospodarkę rynkową, była sprzymierzona ze Stanami Zjednoczonymi, Wielką Brytanią i Francją. Kraj przeżył stopniowy wzrost ekonomiczny, który rozpoczął się w latach pięćdziesiątych. W 1955 r. państwo wstąpiło do NATO, a w 1957 r. było jednym z załorzycieli Wspólnoty Europejskiej. Niemcy Wschodnie należały natomiast do bloku wschodniego i znajdowały się pod gospodarczą i militarną kontrolą Związku Radzieckiego. Mimo że miał być to kraj demokratyczny, władza polityczna sprawowana była jedynie przez ważniejszych członków kontrolowanej przez komunistów Socjalistycznej Partii Jedności Niemiec, wspomaganej przez Ministerstwo Bezpieczeństwa Państwowego NRD, wielką tajną służbę, a także wiele innych organizacji, kontrolujących każdy aspekt życia społecznego[28].

Podczas gdy propaganda Wschodnich Niemiec opierała się na korzyściach programu socjalistycznego oraz strachu przed inwazją Zachodnich Niemiec, wielu obywateli wyjeżdżało na zachód w celu uzyskania wolności i powodzenia[29]. Mur Berliński, zbudowany w 1961 r. w celu powstrzymania mieszkańców Wschodnich Niemiec od uciekania na zachód, stał się symbolem zimnej wojny, a jego upadek w 1989 r., poprzedzony reformami demokratycznymi w Polsce i na Węgrzech, stał się symbolem upadku komunizmu i ponownego zjednoczenia Niemiec[14].

Odbudowa Niemiec[edytuj | edytuj kod]

10 marca 1994 r. Berlin raz jeszcze zyskał miano stolicy Niemiec, podczas gdy Bonn uzyskało status Bundesstadt (miasta federalnego) utrzymując kilka ministrów. Przenosiny rządu ukończono w 1999 r[30]. Po zjednoczeniu, Niemcy zaczęły odgrywać większą rolę w Unii Europejskiej i NATO. Wysłały one misję pokojową na Bałkany, w celu utrzymania tam równowagi, a także do Afrganistanu[31]. W 2005 r., Angela Merkel została pierwszym kanclerzem-kobietą[14].

Geografia[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Niemcy znajdują się w Zachodniej Europie. Na północy graniczą z Danią, na wschodzie z Polską i Republiką Czeską, na wschodzie z Austrią oraz Szwajcarią, na południowym zachodzie z Francją i Luksemburgiem, a na północnym zachodzie z Belgią i Holandią. Leżą w przeważającej części pomiędzy równoleżnikami 47°, a 55° N (fragment wyspy Sylt znajduje się na północ od równoleżnika 55°), oraz południkami 5° i 16° E. Obszar państwa obejmuje 357021km2, w tym 349223 km² na lądzie i 7798 km² na wodzie. Jest to siódmy pod względem wielkości kraj w Europie i 62 na świecie[32].

Niemcy rozciągają się od Alp (z najwyższym szczytem kraju – Zugspitze o wysokości 2962 m n.p.m.) na południu po brzegi Morza Północnego (Nordsee) na północnym zachodzie oraz Bałtyku (Ostsee) na północnym wschodzie. Porośnięte lasami wyżyny centralnych Niemiec oraz niziny na północy kraju (z najniższym punktem – Wilstermarsch o wysokości 3,54 m n.p.m.) przecinają liczne rzeki, np.: Ren, Dunaj i Łaba. Zanikające lodowce górskie pojawiają się w Alpach. Głównymi surowcami naturalnymi są: rudy żelaza, węgiel brunatny, węgiel kamienny, drewno, potas, rudy uranu i miedzi, gaz ziemny, sól kamienna i potasowa, nikiel oraz woda[32].

Klimat[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Większość powierzchni Niemiec temperate seasonal climate in which humid westerly winds predominate. The country is situated in between the oceanic Western European and the continental Eastern European climate. The climate is moderated by the North Atlantic Drift, the northern extension of the Gulf Stream. This warmer water affects the areas bordering the North Sea; consequently in the northwest and the north the climate is oceanic. Germany gets an average of 789 mm (31 in) precipitation per year. Rainfall occurs year-round, with no obligatory dry season. Winters are mild and summers tend to be warm, temperatures can exceed 30 °C (86 °F)[33].

The east has a more continental climate; winters can be very cold and summers very warm, and longer dry periods can occur. Central and southern Germany are transition regions which vary from moderately oceanic to continental. In addition to the maritime and continental climates that predominate over most of the country, the Alpine regions in the extreme south and, to a lesser degree, some areas of the Central German Uplands have a mountain climate, characterised by lower temperatures and greater precipitation[33].

Biodiversity[edytuj | edytuj kod]

The territory of Germany can be subdivided into two ecoregions: European-Mediterranean montane mixed forests and Northeast-Atlantic shelf marine[34]. Szablon:As of the majority of Germany is covered by either arable land (34%) or forest and woodland (30.1%); only 13.4% of the area consists of permanent pastures, 11.8% is covered by settlements and streets[35].

Plants and animals are those generally common to middle Europe. Beeches, oaks, and other deciduous trees constitute one-third of the forests; conifers are increasing as a result of reforestation. Spruce and fir trees predominate in the upper mountains, while pine and larch are found in sandy soil. There are many species of ferns, flowers, fungi, and mosses. Wild animals include deer, wild boar, mouflon, fox, badger, hare, and small numbers of beavers[36]. Germany’s national flower is the blue cornflower[37][38][39][40][41].

The 14 national parks in Germany include the Jasmund National Park, the Vorpommern Lagoon Area National Park, the Müritz National Park, the Wadden Sea National Parks, the Harz National Park, the Hainich National Park, the Saxon Switzerland National Park, the Bavarian Forest National Park and the Berchtesgaden National Park. In addition, there are 14 Biosphere Reserves, as well as 98 nature parks.

More than 400 registered zoos and animal parks operate in Germany, which is believed to be the largest number in any country[42]. The Berlin Zoo opened in 1844 is the oldest zoo in Germany, and presents the most comprehensive collection of species in the world[43].

Politics[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Germany is a federal, parliamentary, representative democratic republic. The German political system operates under a framework laid out in the 1949 constitutional document known as the Grundgesetz (Basic Law). Amendments generally require a two-thirds majority of both chambers of parliament; the fundamental principles of the constitution, as expressed in the articles guaranteeing human dignity, the separation of powers, the federal structure, and the rule of law are valid in perpetuity[44].

The president is the head of state and invested primarily with representative responsibilities and powers. He is elected by the Bundesversammlung (federal convention), an institution consisting of the members of the Bundestag and an equal number of state delegates. The second-highest official in the German order of precedence is the Bundestagspräsident (President of the Bundestag), who is elected by the Bundestag and responsible for overseeing the daily sessions of the body. Szablon:Clear left

|

|

| Joachim Gauck Obecny Prezydent Niemiec w 2012 |

Angela Merkel Obecna Kanclerz Niemiec w 2005 |

The third-highest official and the head of government is the Chancellor, who is appointed by the Bundespräsident after being elected by the Bundestag[45]. The chancellor, currently Angela Merkel, is the head of government and exercises executive power, similar to the role of a Prime Minister in other parliamentary democracies.

Federal legislative power is vested in the parliament consisting of the Bundestag (Federal Diet) and Bundesrat (Federal Council), which together form the legislative body. The Bundestag is elected through direct elections, by proportional representation (mixed-member)[32]. The members of the Bundesrat represent the governments of the sixteen federated states and are members of the state cabinets[45].

Since 1949, the party system has been dominated by the Christian Democratic Union and the Social Democratic Party of Germany. So far every chancellor has been a member of one of these parties. However, the smaller liberal Free Democratic Party (which has had members in the Bundestag since 1949) and the Alliance '90/The Greens (which has had seats in parliament since 1983) have also played important roles[46].

Minor parties such as The Left, Free Voters and the Pirate Party are represented in some state parliaments.

Prawo[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Germany has a civil law system based on Roman law with some references to Germanic law. The Bundesverfassungsgericht (Federal Constitutional Court) is the German Supreme Court responsible for constitutional matters, with power of judicial review[45][47]. Germany’s supreme court system, called Oberste Gerichtshöfe des Bundes, is specialised: for civil and criminal cases, the highest court of appeal is the inquisitorial Federal Court of Justice, and for other affairs the courts are the Federal Labour Court, the Federal Social Court, the Federal Finance Court and the Federal Administrative Court. The Völkerstrafgesetzbuch regulates the consequences of crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes, and gives German courts universal jurisdiction in some circumstances[48].

Criminal and private laws are codified on the national level in the Strafgesetzbuch and the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch respectively. The German penal system is aimed towards rehabilitation of the criminal and the protection of the general public[49]. Except for petty crimes, which are tried before a single professional judge, and serious political crimes, all charges are tried before mixed tribunals on which lay judges ( (niem. • Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: schöffen. Sprawdź listę kodów.)) sit side by side with professional judges[50][51].

Many of the fundamental matters of administrative law remain in the jurisdiction of the states, though most states base their own laws in that area on the 1976 Verwaltungsverfahrensgesetz (Administrative Proceedings Act) covering important points of administrative law. The Oberverwaltungsgerichte are the highest level of administrative jurisdiction concerning the state administrations, unless the question of law concerns federal law or state law identical to federal law. In such cases, final appeal to the Federal Administrative Court is possible.

Constituent states[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Germany comprises sixteen states which are collectively referred to as Länder[52] Each state has its own state constitution[53] and is largely autonomous in regard to its internal organisation. Because of differences in size and population the subdivisions of these states vary, especially as between city states (Stadtstaaten) and states with larger territories (Flächenländer). For regional administrative purposes five states, namely Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Hesse, North Rhine-Westphalia and Saxony, consist of a total of 22 Government Districts (Regierungsbezirke). Szablon:As of Germany is divided into 403 districts (Kreise) at a municipal level; these consist of 301 rural districts and 102 urban districts[54].

|

Foreign relations[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Germany has a network of 229 diplomatic missions abroad[55] and maintains relations with more than 190 countries[56]. Szablon:As of it is the largest contributor to the budget of the European Union (providing 20%)[57] and the third largest contributor to the UN (providing 8%)[58]. Germany is a member of NATO, the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the G8, the G20, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It has played a leading role in the European Union since its inception and has maintained a strong alliance with France since the end of World War II. Germany seeks to advance the creation of a more unified European political, defence, and security apparatus[59][60].

The development policy of the Federal Republic of Germany is an independent area of German foreign policy. It is formulated by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and carried out by the implementing organisations. The German government sees development policy as a joint responsibility of the international community[61]. It is the world’s third biggest aid donor after the United States and France[62][63].

During the Cold War, Germany’s partition by the Iron Curtain made it a symbol of East-West tensions and a political battleground in Europe. However, Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik was a key factor in the détente of the 1970s.[64] In 1999, Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s government defined a new basis for German foreign policy by taking part in the NATO decisions surrounding the Kosovo War and by sending German troops into combat for the first time since World War II[65]. The governments of Germany and the United States are close political allies[45]. The 1948 Marshall Plan and strong cultural ties have crafted a strong bond between the two countries, although Schröder’s vocal opposition to the Iraq War suggested the end of Atlanticism and a relative cooling of German-American relations[66]. The two countries are also economically interdependent: 8.8% of German exports are U.S.-bound and 6.6% of German imports originate from the U.S.[67].

Siły zbrojne[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Rola niemieckiego wojska (Bundeswehr) została opisana w Konstytucji Niemiec (Art. 87a) jako wyłącznie defensywna. Jego jedynymi aktywnymi działaniami przed 1990 r., była pomoc podczas klęsk żywiołowych w kraju i za granicą. W 1994 r. trybunał konstytucyjny termin defensywa został zdefiniowany nie tylko jako obrona granic państwa, ale także zapobieganie innym konfliktom na całym świecie, które mogłyby w jakikolwiek sposób zagrozić państwu.

W 2011 r., wydatki na wojsko stanowiły około 1,3% produktu krajowego brutto, co jest wynikiem niskim na tle innych krajów. Pomimo to, Niemcy są dziewiątym krajem na świecie, który przeznacza najwięcej kosztów na utrzymanie armii[68]. W okresie pokoju wojsko jest dowodzone przez Ministra Obrony. W przypadku znalezienia się kraju w stanie wojny, która zgodnie z konstytucją będzie miała charakter obronny, dowódcą naczelnym zostanie kanclerz[69].

W 2012 r. niemieckie wojsko zatrudniało 183 000 zawodowych żołnierzy i 17 000 ochotników[70]. Niemiecki rząd planuje jednak ograniczenie tych liczb do 170 000 zawodowców i 15 000 ochotników[71]. Rezerwiści są dostępni siłom zbrojnym i uczestniczą w ćwiczeniach obronnych. W 2011 r. Niemieckie wojsko posiadało 6 900 żołnierzy stacjonujących w innych krajach w ramach misji pokojowych, w tym 4900 w Afrganistanie i Uzbekistanie, 1 150 w Kosowie i 300 w Libanie[72].

Do 2011 r. służba wojskowa była obowiązkowa dla mężczyzn w wieku lat 18, a pobór składał się z sześciomiesięcznej śłużby. 1 lipca 2011 r. obowiązek został oficjalnie zniesiony. Po 2001 roku w armii mogły służyć kobiety, ale nie obowiązywał ich ibowiązek służby wojskowej[73]. Obecnie w armii pracuje ok. 17 500 kobiet.

Economy[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Germany has a social market economy with a highly skilled labour force, a large capital stock, a low level of corruption[75], and a high level of innovation[76]. It has the largest and most powerful national economy in Europe, the fourth largest by nominal GDP in the world[77] the fifth largest by PPP[78] and was the biggest net contributor to the EU budget in 2011.[79] The service sector contributes approximately 71% of the total GDP, industry 28%, and agriculture 1%[32]. The official average national unemployment rate in May 2012 was 6.7%[80]. However, the official average national unemployment rate also includes people with a part-time job that are looking for a full-time job.[81] The unofficial average national unemployment rate in 2011 was 5.7%[32].

Germany is an advocate of closer European economic and political integration. Its commercial policies are increasingly determined by agreements among European Union (EU) members and by EU legislation. Germany introduced the common European currency, the euro, on 1 January 2002.[82][83] Its monetary policy is set by the European Central Bank, which is headquartered in Frankfurt. Two decades after German reunification, standards of living and per capita incomes remain significantly higher in the states of the former West Germany than in the former East.[84] The modernisation and integration of the eastern German economy is a long-term process scheduled to last until the year 2019, with annual transfers from west to east amounting to roughly $80 billion[85]. In January 2009 the German government approved a €50 billion economic stimulus plan to protect several sectors from a downturn and a subsequent rise in unemployment rates[86].

Of the world’s 500 largest stock-market-listed companies measured by revenue in 2010, the Fortune Global 500, 37 are headquartered in Germany. 30 Germany-based companies are included in the DAX, the German stock market index. Well-known global brands are Mercedes-Benz, BMW, SAP, Siemens AG, Volkswagen, Adidas, Audi, Allianz, Porsche, Bayer, Bosch, and Nivea[87]. Germany is recognised for its specialised small and medium enterprises. Around 1,000 of these companies are global market leaders in their segment and are labelled hidden champions[88].

The list includes the largest German companies by revenue in 2011:

| Rank[89] | Name | Headquarters | Revenue (Mil. €) |

Profit (Mil. €) |

Employees (World) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Volkswagen AG | Wolfsburg | 159.000 | 15.800 | 502.000 |

| 2. | E.ON SE | Düsseldorf | 113.000 | −1.900 | 79.000 |

| 3. | Daimler AG | Stuttgart | 107.000 | 6.000 | 271.000 |

| 4. | Siemens AG | Berlin, München | 74.000 | 6.300 | 360.000 |

| 5. | BASF SE | Ludwigshafen am Rhein | 73.000 | 6.600 | 111.000 |

| 6. | BMW AG | München | 69.000 | 4.900 | 100.000 |

| 7. | Metro AG | Düsseldorf | 67.000 | 740 | 288.000 |

| 8. | Schwarz-Gruppe (Lidl/Kaufland) | Neckarsulm | 63.000 | N/A | 315.000 |

| 9. | Deutsche Telekom AG | Bonn | 59.000 | 670 | 235.000 |

| 10. | Deutsche Post AG | Bonn | 53.000 | 1.300 | 471.000 |

| – | Allianz SE | München | 104.000 | 2.800 | 141.000 |

| – | Deutsche Bank AG | Frankfurt am Main | 2.160.000 | 4.300 | 101.000 |

Infrastruktura[edytuj | edytuj kod]

With its central position in Europe, Germany is a transport hub. This is reflected in its dense and modern transport networks. The motorway (Autobahn) network ranks as the third-largest worldwide in length and is known for its lack of a general speed limit[90]. Germany has established a polycentric network of high-speed trains. The InterCityExpress or ICE network of the Deutsche Bahn serves major German cities as well as destinations in neighbouring countries with speeds up to 300 kph (186 mph)[91]. The largest German airports are Frankfurt Airport and Munich Airport, both hubs of Lufthansa, while Air Berlin has hubs at Berlin Tegel and Düsseldorf. Other major airports include Berlin Schönefeld, Hamburg, Cologne/Bonn and Leipzig/Halle. Both airports in Berlin will be consolidated at a site adjacent to Berlin Schönefeld, which will become Berlin Brandenburg Airport[92].

Szablon:As of, Germany was the world’s sixth-largest consumer of energy[93], and 60% of its primary energy was imported[94]. Government policy promotes energy conservation and renewable energy commercialisation. Energy efficiency has been improving since the early 1970s; the government aims to meet the country’s electricity demands using 40% renewable sources by 2020 and 100% by 2050.[95] In 2010, energy sources were: oil (33.7%); coal, including lignite (22.9%); natural gas (21.8%); nuclear (10.8%); hydro-electric and wind power (1.5%); and other renewable sources (7.9%)[96]. In 2000, the government and the nuclear power industry agreed to phase out all nuclear power plants by 2021.[97] Germany is committed to the Kyoto protocol and several other treaties promoting biodiversity, low emission standards, recycling, and the use of renewable energy, and supports sustainable development at a global level[98]. The German government has initiated wide-ranging emission reduction activities and the country’s overall emissions are falling[99]. Nevertheless the country’s greenhouse gas emissions were the highest in the EU Szablon:As of[100].

Science and technology[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Germany’s achievements in the sciences have been significant, and research and development efforts form an integral part of the economy[101]. The Nobel Prize has been awarded to 103 German laureates[102]. For most of the 20th century, German laureates had more awards than those of any other nation, especially in the sciences (physics, chemistry, and physiology or medicine)[103][104].

The work of Albert Einstein and Max Planck was crucial to the foundation of modern physics, which Werner Heisenberg and Max Born developed further[105]. They were preceded by such key physicists as Hermann von Helmholtz, Joseph von Fraunhofer and Gabriel Daniel Fahrenheit, among others. Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays and was the first winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901.[106] Otto Hahn was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry and discovered nuclear fission[107], while Ferdinand Cohn and Robert Koch were founders of microbiology. Numerous mathematicians were born in Germany, including Carl Friedrich Gauss, David Hilbert, Bernhard Riemann, Gottfried Leibniz, Karl Weierstrass, Hermann Weyl and Felix Klein. Research institutions in Germany include the Max Planck Society, the Helmholtz Association and the Fraunhofer Society. The Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize is granted to ten scientists and academics every year. With a maximum of €2.5 million per award it is one of highest endowed research prizes in the world[108].

Germany has been the home of many famous inventors and engineers, such as Johannes Gutenberg, credited with the invention of movable type printing in Europe; Hans Geiger, the creator of the Geiger counter; and Konrad Zuse, who built the first fully automatic digital computer[109]. German inventors, engineers and industrialists such as Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, Otto Lilienthal, Gottlieb Daimler, Rudolf Diesel, Hugo Junkers and Karl Benz helped shape modern automotive and air transportation technology[110]. Aerospace engineer Wernher von Braun developed the first space rocket and later on was a prominent member of NASA and developed the Saturn V Moon rocket, which paved the way for the success of the US Apollo program. Heinrich Rudolf Hertz’s work in the domain of electromagnetic radiation was pivotal to the development of modern telecommunication[111].

Germany is one of the leading countries in developing and using green technologies. Companies specializing in green technology have an estimated turnover of €200 billion. Key sectors of Germany’s green technology industry are power generation, sustainable mobility, material efficiency, energy efficiency, waste management and recycling, and sustainable water management[112].

Demografia[edytuj | edytuj kod]

With its estimated population of 81.8 million in January 2010[113], Germany is the most populous country in the European Union and ranks as the 16th most populous country in the world[114]. Its population density stands at 229.4 inhabitants per square kilometre. The overall life expectancy in Germany at birth is 80.19 years (77.93 years for males and 82.58 years for females)[32]. The fertility rate of 1.41 children born per woman (2011 estimates), or 8.33 births per 1000 inhabitants, is one of the lowest in the world[32]. Since the 1970s, Germany’s death rate has continuously exceeded its birth rate[115]. The Federal Statistical Office of Germany has forecast that the population could shrink to between 65 and 70 million by 2060 (depending on the level of net migration)[116] However, such forecasts have often been proven wrong in the past, and Germany is currently witnessing increased birth rates[117] and migration rates since the beginning of the 2010s. It is notably experiencing a strong increase in the number of well-educated migrants[118][119]. In 2012, 300,000 more immigrants than emigrants were reported in Germany[120].

Germans by nationality make up 91% of the population of Germany. Szablon:As of, about seven million foreign citizens were registered in Germany, and 20%[121] of the country’s residents, or more than 16 million people, were of foreign or partially foreign descent (including persons descending or partially descending from ethnic German repatriates), 96% of whom lived in the former West Germany or Berlin[122]. In 2010, 2.3 million families with children under 18 years were living in Germany, in which at least one parent had foreign roots. They represented 29% of the total of 8.1 million families with minor children. Compared with 2005 – the year when the microcensus started to collect detailed information on the population with a migrant background – the proportion of migrant families has risen by 2 percentage points[123].

Most of the families with a migrant background live in the western part of Germany. In 2010, the proportion of migrant families in all families was 32% in the pre-unification territory of the Federal Republic. This figure was more than double that in the new Länder (including Berlin) where it stood at 15%[123]. Families with a migrant background more often have three or more minor children in the household than families without a migrant background. In 2010, about 15% of the families with a migrant background contained three or more minor children, as compared with just 9% of the families without a migrant background[123].

The United Nations Population Fund lists Germany as host to the third-highest number of international migrants worldwide, about 5% or 10 million of all 191 million migrants[124]. As a consequence of restrictions to Germany’s formerly rather unrestricted laws on asylum and immigration, the number of immigrants seeking asylum or claiming German ethnicity (mostly from the former Soviet Union) has been declining steadily since 2000.[125] In 2009, 20% of the population had immigrant roots, the highest since 1945.[126] Szablon:As of, the largest national group was from Turkey (2.5 million), followed by Italy (776,000) and Poland (687,000)[127]. About 3 million „Aussiedler” – ethnic Germans, mainly from the former eastern bloc – have resettled in Germany since 1987.[128] Large numbers of people with full or significant German ancestry are found in the United States[129] and Canada[130]. Most ethnic minorities (especially those of non-European origin) reside in large urban areas like Berlin, Hamburg, Frankfurt Rhine-Main, Rhine-Ruhr, Rhine-Neckar and Munich. The percentage of non-Germans and immigrants is rather low in rural areas and small towns, especially in the East German states of the former GDR territory.

Germany is home to the third-highest number of international migrants worldwide[131]. Ethnic composition in 2010:

| Ethnic Group | %[132][133] | population |

|---|---|---|

| European | 88.0 | 71,935,000 |

| Ethnic German | 80.7 | 65,970,000 |

| Polish | 2.0 | 1,654,000 |

| former Soviet Union (primarily Russian Germans, Russians and Jews) | 1.7 | 1,400,000 |

| European Other (Western Europeans and former Yugoslavians) | 3.6 | 3,000,000 |

| Middle Eastern | 5.2 | 4,260,000 |

| Turkish | 4.0 | 3,260,000 |

| others (primarily Arabs and Iranians) | 1.2 | 1,000,000 |

| Asian | 2.0 | 1,634,000 |

| Afro-German or Black African | 1.0 | 817,150 |

| Mixed or unspecified background | 2.0 | 1,634,000 |

| Other groups (primarily the Americas) | 1.8 | 1,470,000 |

| Total population | 100 | 81,715,000 |

Germany has a number of large cities. There are 11 officially recognised metropolitan regions in Germany – and since 2006, 34 potential cities were identified which can be called a Regiopolis.

The largest conurbation is the Rhine-Ruhr region (11.7 million Szablon:As of), including Düsseldorf (the capital of North Rhine-Westphalia), Cologne, Bonn, Dortmund, Essen, Duisburg, and Bochum[134].

Szablon:Largest cities of Germany

Religia[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Największą religią w Niemczech jest chrześcijaństwo, z 51,5 milionem wiernych (62,8%) w 2008 roku[135]. Na tle całej populacji, 30.0% mieszkańców Niemiec to Katolicy, 29,9% to Protestanci należacy do Niemieckiego Kościoła Ewangelickiego, a pozostali chrześcijanie przynależą do mniejszych wyznań, liczących mniej niż 0,5% wiernych[136]. Protestantyzm dominuje na północy i wschodzie państwa, a katolicyzm na południu i zachodzie[3]; 1,6% wszystkich mieszkańców kraju deklaruje, że wyznają prawosławie[135].

Drugą religią w Niemczech jest Islam z 3,8 do 4,3 miliona wiernych (4,6% do 5,2%)[137], który wyprzedza Buddyzm, liczący 250 000 wyznawców i Judaizm z ok. 200 000 przynależnych Niemców (0,3%). Hinduizm posiada ok. 90 000 wiernych (0,1%). Pozostałe społeczności religijne w Niemczech liczą poniżej 50 000 wiernych[138]. Z ok. 4 milionów Muzułmanów, większość stanowią Sunnici, ale mieszka tu niewielka liczba Szyitów i wyznawców innych odłamów islamu[137]. Niemcy posiadają trzecią w Europie społeczność żydowską (po Francji i Wielkiej Brytanii)[139]. Około 50% niemieckich buddystów stanowią natomiast imigranci z Azji[140].

Niemcy nie deklarujący przynależności do żadnej religii stanowią 34,1% populacji i są skoncentrowani na terenie dawnej Niemieckiej Republiki Demokratycznej i w dużych kompleksach miejskich[136]. Zjednoczenie Niemiec w 1990 znacznie zwiększyło odsetek ateistów w populacji, co jest dziedzictwem ateizmu państwowego w dawnym Związku Radzieckim, który kontrolował wschodnią część dzisiejszych Niemiec. Liczba chrześcijan, szczególnie Protestantów spadła w ostatnich latach[3].

Languages[edytuj | edytuj kod]

German is the official and predominant spoken language in Germany[142]. It is one of 23 official languages in the European Union, and one of the three working languages of the European Commission.

Recognised native minority languages in Germany are Danish, Low German, Sorbian, Romany, and Frisian; they are officially protected by the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. The most used immigrant languages are Turkish, Kurdish, Polish, the Balkan languages, and Russian. 67% of German citizens claim to be able to communicate in at least one foreign language and 27% in at least two languages other than their own.[142]

Standard German is a West Germanic language and is closely related to and classified alongside English, Low German, Dutch, and the Frisian languages. To a lesser extent, it is also related to the East (extinct) and North Germanic languages. Most German vocabulary is derived from the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family[143]. Significant minorities of words are derived from Latin and Greek, with a smaller amount from French and most recently English (known as Denglisch). German is written using the Latin alphabet. German dialects, traditional local varieties traced back to the Germanic tribes, are distinguished from varieties of standard German by their lexicon, phonology, and syntax[144].

Edukacja[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Over 99% of Germans age 15 and above are estimated to be able to read and write[32]. Responsibility for educational supervision in Germany is primarily organized within the individual federal states. Since the 1960s, a reform movement attempted to unify secondary education in a Gesamtschule (comprehensive school); several West German states later simplified their school system to two or three tiers. A system of apprenticeship called Duale Ausbildung („dual education”) allows pupils in vocational training to learn in a company as well as in a state-run vocational school[146]. This successful model is highly regarded and reproduced all around the world[147].

Optional kindergarten education is provided for all children between three and six years old, after which school attendance is compulsory for at least nine years. Primary education usually lasts for four to six years and public schools are not stratified at this stage[146]. In contrast, secondary education includes three traditional types of schools focused on different levels of academic ability: the Gymnasium enrols the most gifted children and prepares students for university studies; the Realschule for intermediate students lasts six years; the Hauptschule prepares pupils for vocational education[148].

The general entrance requirement for university is Abitur, a qualification normally based on continuous assessment during the last few years at school and final examinations; however there are a number of exceptions, and precise requirements vary, depending on the state, the university and the subject. Germany’s universities are recognised internationally; in the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) for 2008, six of the top 100 universities in the world are in Germany, and 18 of the top 200.[149] Most of the German universities are public institutions, charging tuition fees of only around €60 per semester (and up to €500 in the state of Niedersachsen) for each student[150][151]. Thus, academic education is open to most citizens and studying is increasingly common in Germany[152]. Although the dual education system, that combines practical and theoretical educations and does not lead to academic degrees, is typical for Germany and recognized as a role model for other countries[153].

The oldest universities of Germany are also among the oldest and best regarded in the world, with Heidelberg University being the oldest (established in 1386 and in continuous operation since then). It is followed by Leipzig University (1409), Rostock University (1419), Greifswald University (1456), Freiburg University (1457), LMU Munich (1472) and the University of Tübingen (1477).

Most German universities focus more on teaching than on research. Research is mostly exhibited in independent institutes that are embedded in academic clusters, such as within Max Planck, Fraunhofer, Leibniz and Helmholtz institutes. This German specialization is rarely reflected in academic rankings, which is the reason why German universities seem to be underperforming according to some of the ratings, such as ARWU. Some German universities are shifting their focus more towards research though, especially the institutes of technology.

Health[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Germany has the world’s oldest universal health care system, dating back to Bismarck’s social legislation in 1883.[154] Currently the population is covered by a fairly comprehensive health insurance plan provided by statute. Certain groups of people (lifetime officials, self-employed persons, employees with high income) can opt out of the plan and switch to a private insurance contract. Previously, these groups could also choose to do without insurance, but this option was dropped in 2009.[155] According to the World Health Organization, Germany’s health care system was 77% government-funded and 23% privately funded Szablon:As of[156]. In 2005, Germany spent 11% of its GDP on health care. Germany ranked 20th in the world in life expectancy with 77 years for men and 82 years for women, and it had a very low infant mortality rate (4 per 1,000 live births)[156].

Szablon:As of, the principal cause of death was cardiovascular disease, at 41%, followed by malignant tumours, at 26%[157].

Szablon:As of, about 82,000 Germans had been infected with HIV/AIDS and 26,000 had died from the disease (cumulatively, since 1982)[158]

According to a 2005 survey, 27% of German adults are smokers[158].

Kultura[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Kultura Niemiec została w znacznym stopniu ukształtowana przez główne prądy w modzie i nauce Europy, zarówno religijne, jak i świeckie. Dawniej Niemcy nazywane były krajem poetów i myślicieli[159], ze względu na duży wkład literatów oraz filozofów w rozwój światowej nauki i kultury.

Za instytucje kulturalne w Niemczech odpowiedzialne są poszczególne kraje związkowe. Znajduje się tu ok. 240 teatrów, setki filcharmonii i oper, tysiące muzeów i ponad 25 000 bibliotek. Możliwości te wykorzystują mieszkańcy kraju: co roku 91 milionów Niemców odwiedza muzea, a 20 milionów uczęszcza do teatrów i oper, podczas gdy 3.6 miliona słucha koncertów orkiestr symfonicznych[160]. W roku 2012 w Niemczech znajdowało się 37 obiektów wpisanych na listę UNESCO[161].

Sztuka[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Numerous German painters have enjoyed international prestige through their work in diverse artistic styles. Albrecht Dürer, Hans Holbein the Younger, Matthias Grünewald and Lucas Cranach the Elder were important artists of the Renaissance, Peter Paul Rubens and Johann Baptist Zimmermann of Baroque, Caspar David Friedrich and Carl Spitzweg of Romanticism, Max Liebermann of Impressionism and Max Ernst of Surrealism.

Several German artist groups formed in the 20th century, such as the November Group or Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) in Expressionism. The New Objectivity arose as a counter-style to it during the Weimar Republic. After WWII, main movements of Neo-expressionism, performance art and Conceptual art evolved, with notable artists such as Joseph Beuys, Gerhard Richter, Jörg Immendorff, HA Schult, Aris Kalaizis, Neo Rauch (New Leipzig School) and Andreas Gursky (photography). Major art exhibitions and festivals in Germany are the documenta, transmediale and Art Cologne.

Muzyka[edytuj | edytuj kod]

| J.S. Bach Toccata und Fuge |

L.v. Beethoven Symphonie 5 c-moll |

R. Wagner Die Walküre |

|---|---|---|

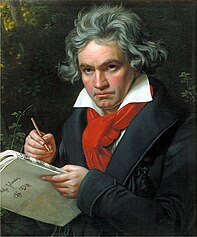

German classical music comprises works by some of the world’s most well-known composers, including Ludwig van Beethoven, Johann Sebastian Bach, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Johannes Brahms, Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss.

Germany is the largest music market in Europe, and third largest in the world[162]. German popular music of the 20th and 21st century includes the movements of Neue Deutsche Welle (Nena, Alphaville), Ostrock (City, Keimzeit), Metal/Rock (Rammstein, Scorpions), Punk (Die Ärzte, Die Toten Hosen), Pop-rock (Beatsteaks, Tokio Hotel), Indie (Tocotronic, Blumfeld) and Hip Hop (Die Fantastischen Vier, Deichkind). Especially the German Electronic music gained global influence, with Kraftwerk being a pioneer group in this genre[163], and the Minimal and Techno scenes in Germany being very popular (e.g. Paul van Dyk, Tomcraft, Paul Kalkbrenner and Scooter).

Architektura[edytuj | edytuj kod]

Architectural contributions from Germany include the Carolingian and Ottonian styles, which were precursors of Romanesque. Brick Gothic in medieval times and Brick Expressionism in modern times are two distinctive styles that developed in Germany. Also in Renaissance and Baroque art, regional and typically German elements evolved (e.g. Weser Renaissance and Dresden Baroque).

Germany is especially renowned for its timber frame old towns, with many well-kept examples to be found along the German Timber-Frame Road, leading from the very south of Germany to Northern Germany and its coasts.

When industrialization spread across Europe, Classicism and a distinctive style of historism developed in Germany, sometimes referred to as Gründerzeit style, due to the economical boom years at the end of the 19th century. Resort architecture and Spa architecture are sub-styles, that evolved since the 18th century in Germany, with the first modern spas and Seaside resorts of Europe. Many architects formed this era, with Schinkel, Semper, von Gärtner, Schwechten and Lipsius among them.

Jugendstil became a dominant architectural style at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, with a strong influence of the Art Nouveau movement[164]. The Art Deco movement did not gain much influence in Germany, instead the Expressionist architecture spread across the country, with e.g. Höger, Mendelsohn, Böhm and Schumacher being influential architects.

Germany was particularly important in the early modern movement – it is the home of the Bauhaus movement founded by Walter Gropius. And thus Germany is a cradle of modern architecture. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe became one of the world’s most renowned architects in the second half of the 20th century. He conceived of the glass façade skyscraper[165].

Renowned contemporary architects include Hans Kollhoff, Helmut Jahn, Behnisch, Albert Speer Junior, Frei Otto, Oswald Mathias Ungers, Gottfried Böhm, Stephan Braunfels and Anna Heringer.

Literatura i filozofia[edytuj | edytuj kod]

German literature can be traced back to the Middle Ages and the works of writers such as Walther von der Vogelweide and Wolfram von Eschenbach. Well-known German authors include Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and Theodor Fontane. The collections of folk tales published by the Brothers Grimm popularised German folklore on an international level. Influential authors of the 20th century include Gerhart Hauptmann, Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse, Heinrich Böll and Günter Grass[166]. German-speaking book publishers produce some 700 million books every year, with about 80,000 titles, nearly 60,000 of them new. Germany comes third in quantity of books published, after the English-speaking book market and the People’s Republic of China[167]. The Frankfurt Book Fair is the most important in the world for international deals and trading, with a tradition spanning over 500 years[168].

German philosophy is historically significant. Gottfried Leibniz’s contributions to rationalism; the enlightenment philosophy by Immanuel Kant; the establishment of classical German idealism by Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling; Arthur Schopenhauer’s composition of metaphysical pessimism; the formulation of communist theory by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels; Friedrich Nietzsche’s development of perspectivism; Gottlob Frege’s contributions to the dawn of analytic philosophy; Martin Heidegger’s works on Being; and the development of the Frankfurt school by Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse and Jürgen Habermas have been particularly influential. In the 21st century, Germany has contributed to the development of contemporary analytic philosophy in continental Europe, along with France, Austria, Switzerland and the Scandinavian countries[169].

Media[edytuj | edytuj kod]

German cinema dates back to the earliest years of the medium, it has made major technical and artistic contributions to film, as with the work of Max Skladanowsky, who showed the first film sequences ever to an audience, in 1895. Early German cinema was particularly influential with German expressionists such as Robert Wiene and Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. Director Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) is referred to as the first modern science-fiction film. In 1930 the Austrian-American Josef von Sternberg directed The Blue Angel, the first major German sound film[171].

During the 1970s and 1980s, New German Cinema directors such as Volker Schlöndorff, Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder put West German cinema on the international stage[172]. The annual European Film Awards ceremony is held every other year in Berlin, home of the European Film Academy (EFA); the Berlin Film Festival, held annually since 1951, is one of the world’s foremost film festivals[173].

In the 21st century, several German movies have had international success, such as Nowhere in Africa (2001), Das Experiment (2001), Good Bye, Lenin! (2003), Gegen die Wand (Head-On) (2004), Der Untergang (Downfall) (2004), Perfume (2006), The Baader Meinhof Complex (2008), The Wave (2008), The White Ribbon (2009), Pandorum (2009), Soul Kitchen (2009), Animals United (2010), Combat Girls (2011) and Cloud Atlas (2012). The Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film went to the German production Die Blechtrommel (The Tin Drum) in 1979, to Nowhere in Africa in 2002, and to Das Leben der Anderen (The Lives of Others) in 2007.[174]

Germany’s television market is the largest in Europe, with some 34 million TV households. Around 90% of German households have cable or satellite TV, with a variety of free-to-view public and commercial channels[175]. The most watched television broadcast of all-time in Germany was the Germany vs Spain semi-fnal game of the 2010 FIFA World Cup[176]. Nine out of ten of the top ten most watched television broadcasts of all-time in Germany feature the German national football team.

Cuisine[edytuj | edytuj kod]

German cuisine varies from region to region. The southern regions of Bavaria and Swabia, for instance, share a culinary culture with Switzerland and Austria. In all regions, meat is often eaten in sausage form.[177] Organic food has gained a market share of ca. 2%, and is expected to increase further[178]. Although wine is becoming more popular in many parts of Germany, the national alcoholic drink is beer. German beer consumption per person is declining, but at 121.4 litres in 2009 it is still among the highest in the world[179]. The Michelin guide has awarded nine restaurants in Germany three stars, the highest designation, while 15 more received two stars[180]. German restaurants have become the world’s second-most decorated after France[181].

Pork, beef, and poultry are the main varieties of meat consumed in Germany, with pork being the most popular. The average person in Germany will consume up to 61 kg (134 lb) of meat in a year. Among poultry, chicken is most common, although duck, goose, and turkey are also enjoyed. Game meats, especially boar, rabbit, and venison are also widely available all year round. Trout is the most common freshwater fish on the German menu; pike, carp, and European perch also are listed frequently. Vegetables are often used in stews or vegetable soups, but are also served as side dishes. Carrots, turnips, spinach, peas, beans, broccoli and many types of cabbage are very common. A wide variety of cakes and tarts are served throughout the country, most commonly made with fresh fruit. Apples, plums, strawberries, and cherries are used regularly in cakes. Cheesecake is also very popular, often made with quark. Schwarzwälder Kirschtorte (Black Forest cake, made with cherries) is probably the most well-known example of a wide variety of typically German tortes filled with whipped or butter cream.

Sport[edytuj | edytuj kod]

27 milionów Niemców jest członkami klubów sportowych, a dodatkowe dwanaście milionów uprawia sport indywidualnie[182]. Piłka nożna jest najbardziej popularną dyscypliną sportu. Z ponad 6,3 milionem oficjalnych członków, Niemiecki Związek Piłki Nożnej (Deutscher Fußball-Bund) jest największą tego typu organizacją na świecie[182]. Bundesliga, najwyższy poziom rozgrywek w niemieckiej piłce nożnej, jest najpopularniejszą ligą sportową w kraju i odnotowuje drugą największą na świecie frekwencję podczas meczów jakichkolwiek lig sportowych na świecie.

Reprezentacja Niemiec w piłce nożnej zdobyła puchar mistrzostw świata trzykrotnie – w 1954, 1974 oraz 1990 roku. Tyle samo razy zawodnicy niemieccy triumfowali w rozgrywkach mistrzostw Europy – w 1972, 1980 oraz 1996 r. Jednocześnie państwo gościło mistrzostwa świata w 1974 i 2006, a mistrzostwa kontynentu w 1988 roku. Najbardziej znanymi piłkarzami, pochodzącymi z Niemiec są Franz Beckenbauer, Gerd Müller, Jürgen Klinsmann, Lothar Matthäus oraz Oliver Kahn. Poza tym, w Niemczech popularne są także piłka ręczna, siatkówka, koszykówka, hokej na lodzie oraz tenis[182].

Niemcy są także jednym z czołowych państw w sportach motorowych. Konstruktorzy, tacy jak BMW i Mercedes są istotnymi producentami samochodów używanych podczas wyścigów samochodowych. Ponadto, firma Porsche wygrała wyścig Le Mans 24 Hours, trwający dobę wyścig we Francji, szesnaście razy, natomiast Audi zwyciężyło 11 razy. Kierowca preztiżowego cyklu Formuły 1 Michael Schumacher ustanowił podczas swojej kariery wiele rekordów w sportach motorowych, wygrywając najwięcej wyścigów i Pucharów Świata w historii. Jest także jednym z najbogatszych sportowców[183].

Niemieccy sportowcy regularnie osiągają bardzo wysokie wyniki podczas Igrzysk olimpijskich. Są sklasyfikowani na trzecim miejscu w klasyfikacji medalowej wszech czasów, łącząc wyniki Niemiec Wschodnich i Niemiec Zachodnich. Podczas Letnich Igrzysk Olimpijskich w 2012 roku, Niemcy zakończyli rywalizację na szóstej pozycji w klasyfikacji medalowej[184], podczas gdy na Zimowych Igrzyskach Olimpijskich w 2010 roku zajęli w niej drugie miejsce[185]. Niemcy organizowały letnie igrzyska olimpijskie dwukrotnie, w Berlinie w 1936 roku oraz w Monachium w 1972 r. Ponadto, Garmisch-Partenkirchen gościło zimowe igrzyska w 1936 r.

Zobacz też[edytuj | edytuj kod]

- Index of Germany-related articles

- Outline of Germany

- Metropolitan regions in Germany

- List of cities in Germany by population

- List of cities and towns in Germany

References[edytuj | edytuj kod]

- ↑ Max Mangold: Duden, Aussprachewörterbuch. Wyd. 6th. Dudenverlag, 1995, s. 271, 53f. ISBN 978-3-411-20916-3. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.).

- ↑ The Latin name Sacrum Imperium (Holy Empire) is documented as far back as 1157. The Latin name Sacrum Romanum Imperium (Holy Roman Empire) was first documented in 1254. The full name „Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation” (Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation) dates back to the 15th century.

.Reinhold Zippelius: Kleine deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte: vom frühen Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. Wyd. 7th. Munich: Beck, 2006, s. 25. ISBN 978-3-406-47638-9. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.). - ↑ a b c Germany. Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. [dostęp 15 December 2011].

- ↑ Hagen Schulze: Germany: A New History. Harvard University Press, 1998, s. 4. ISBN 0-674-80688-3.

- ↑ Albert L. Lloyd: Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Althochdeutschen, Band II. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1998, s. 699–704. ISBN 3-525-20768-9. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.). (for diutisc) Albert L. Lloyd: Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Althochdeutschen, Band II. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1998, s. 685–686. ISBN 3-525-20768-9. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.). (for diot)

- ↑ Jill Claster: Medieval Experience: 300-1400. New York University Press, s. 35. ISBN 0-8147-1381-5.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Fulbrook: {{{tytuł}}}. 1991, s. 9–24.

- ↑ Alan K. Bowman, Garnsey, Peter, Cameron, Averil: The crisis of empire, A.D.193-337. Cambridge Univeristy Press, 2005, s. 442. ISBN 0-521-30199-8.

- ↑ Lynn Harry Nelson: The Great Famine (1315-1317) and the Black Death (1346-1351). University of Kansas.

- ↑ Daniel Phillipot: The Religious Roots of Modern International Relations. styczeń 2000.

- ↑ Alan Macfarlane: The savage wars of peace: England, Japan and the Maltusian trap. s. 51. ISBN 987-0-631-18117-0.

- ↑ G. Gagliardo: Reich and Nation, The Holy Roman Empire as Idea and Reality, 1763-1806. Indiana University Press, 1980, s. 12–13.

- ↑ W.O. Henderson: The Zollverein. styczeń 1934, s. 1–19.

- ↑ a b c d e Germany. 10 listopada 2010. [dostęp 2013-08-11].

- ↑ John Black: 100 maps. Sterling Publishing, 2005, s. 202. ISBN 978-1-4027-2885-3.

- ↑ David Crossland: Last German World War I Veteran Believed to Have Died. Spiegel, 22 stycznia 2008. [dostęp 2013-08-11].

- ↑ Stephen J. Lee: Europe, 1890-1945. 2003, s. 131. ISBN 978-0-415-25455-7.

- ↑ Das Ermächtigungsgesetz 1933. [dostęp 2013-08-11]. (niem.).

- ↑ Roderick Stackelberg: Hitler’s Germany:Origins, interpretations, legacies. 1999, s. 103. ISBN 978-0-415-20115-5.

- ↑ Industrie und Wirtschaft. [dostęp 2013-08-11]. (niem.).

- ↑ Heinz Gunter Steinberg: Die Bevölkerungsentwicklung in Deutschland im Zweiten Weltkrieg: mit einem Überblick über die Entwicklung von 1945 bis 1990. 1991. ISBN 978-3-88557-089-9.

- ↑ Donald L. Niewyk, Francis R. Nicosia: The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust. Columbia University Press, 2000, s. 45–52. ISBN 978-0-231-11200-0.

- ↑ Leaders mourn Soviet wartime dead. 9 maja 2005. [dostęp 2013-08-11].

- ↑ Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg. s. 460. ISBN 3-421-06236-6.

- ↑ Antony Beevor: Berlin: The downfall 1945. 2003, s. 31–32, 409–412. ISBN 978-0-14-028696-0.

- ↑ Richar J. Evans: The Other Horror. The New Republic, 21 czerwca 2012. [dostęp 2013-08-11].

- ↑ Michael Z. Wise: Capital dilemma: Germany’s search for a new architecture of democracy. Princeton Architectural Press, 1998, s. 23. ISBN 978-1-56898-134-5.

- ↑ Nico Cochester: D-mark day dawns. Financial Times, 1 stycznia 2001. [dostęp 2013-08-11].

- ↑ Ferdinand Protzman: Westward Tide of East Germans Is a Popular No-Confidence Vote. 22 sierpnia 1989. [dostęp 2013-08-11].

- ↑ Brennpunkt: Hauptstadt-Umzug. Focus, 12 kwietnia 1999. [dostęp 2013-08-11].

- ↑ Judy Dempsey: Germany is planning a Bosnia withdrawal. 31 października 2006. [dostęp 2013-08-11].

- ↑ a b c d e f g h World Factbook. CIA. [dostęp 26 March 2011].

- ↑ a b Climate in Germany. GermanCulture. [dostęp 26 March 2011].

- ↑ Terrestrial Ecoregions. WWF. [dostęp 19 March 2011].

- ↑ Kathrin Strohm: Arable farming in Germany. Agri benchmark, May 2010. [dostęp 14 April 2011].

- ↑ Henk Bekker: Adventure Guide Germany. Hunter, 2005, s. 14. ISBN 978-1-58843-503-3.

- ↑ The Handy Science Answer Book: Cornflower. Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. [dostęp 15 May 2013].

- ↑ Education & Advice: Cornflower. UK Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust. [dostęp 14 May 2013].

- ↑ CORNFLOWER (Centaurea cyanus). Encyclopaedia Britannica, Volume 6. [dostęp 15 May 2013].

- ↑ Norman Taylor: One Thousand One Questions Answered about Flowers. Constable and Company, London, 1996, s. 201.

- ↑ Susan J. Wernert: Reader’s Digest North American Wildlife. Reader’s Digest Association, 1998, s. 462.

- ↑ Zoo Facts. Zoos and Aquariums of America. [dostęp 16 April 2011].

- ↑ Der Zoologische Garten Berlin. Zoo Berlin. [dostęp 19 March 2011]. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.).

- ↑ Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany. [w:] Deutscher Bundestag [on-line]. Btg-bestellservice, October 2010. [dostęp 14 April 2011].

- ↑ a b c d Germany. U.S. Department of State, 10 November 2010. [dostęp 26 March 2011].

- ↑ Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union. U.S. Library of Congress. [dostęp 26 March 2011].

- ↑ Federal Constitutional Court. Bundesverfassungsgericht. [dostęp 26 March 2011].

- ↑ Völkerstrafgesetz Teil 1 Allgemeine Regelungen. Bundesministerium der Justiz. [dostęp 19 April 2011]. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.).

- ↑ § 2 Strafvollzugsgesetz. Bundesministerium der Justiz. [dostęp 26 March 2011]. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.).

- ↑ Jörg-Martin Jehle, German Federal Ministry of Justice: Criminal Justice in Germany. Forum-Verlag, 2009, s. 23. ISBN 978-3-936999-51-8.

- ↑ Gerhard Casper, Hans Zeisel. Lay Judges in the German Criminal Courts. „Journal of Legal Studies”. 1 (1), s. 141, January 1972. JSTOR: 724014.

- ↑ The individual denomination is either Land [state], Freistaat [free state] or Freie (und) Hansestadt [free (and) Hanseatic city].

.The Federal States. [w:] www.bundesrat.de [on-line]. Bundesrat of Germany. [dostęp 17 July 2011].

Amtliche Bezeichnung der Bundesländer. [w:] www.auswaertiges-amt.de [on-line]. Federal Foreign Office. [dostęp 22 October 2011]. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.). - ↑ Example for state constitution: „Constitution of the Land of North Rhine-Westphalia”. Landtag (state assembly) of North Rhine-Westphalia. [dostęp 17 July 2011].

- ↑ Kreisfreie Städte und Landkreise nach Fläche und Bevölkerung 31.12.2010. Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland, October 2011. [dostęp 6 April 2012]. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.).

- ↑ German Missions Abroad. German Federal Foreign Office. [dostęp 26 March 2011].

- ↑ The Embassies. German Federal Foreign Office. [dostęp 18 July 2012].

- ↑ The EU budget 2011 in figures. European Commission. [dostęp 6 May 2011].

- ↑ United Nations regular budget for the year 2011. UN Committee on Contributions. [dostęp 6 May 2011].

- ↑ Declaration by the Franco-German Defence and Security Council. French Embassy UK, 13 May 2004. [dostęp 19 March 2011].

- ↑ Freed, John C: The leader of Europe? Answers an ocean apart. The New York Times, 4 April 2008. [dostęp 28 March 2011].

- ↑ Aims of German development policy. Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, 10 April 2008. [dostęp 26 March 2011].

- ↑ Net Official Development Assistance 2009. OECD. [dostęp 26 March 2011].

- ↑ Speech by Chancellor Angela Merkel to the United Nations General Assembly. [w:] Die Bundesregierung [on-line]. 21 September 2010. [dostęp 18 March 2011].

- ↑ Hope Harrison. American détente and German ostpolitik, 1969–1972. „Bulletin Supplement”. 1, 2004. German Historical Institute. [dostęp 26 March 2011].

- ↑ Germany’s New Face Abroad. [w:] Deutsche Welle [on-line]. 14 October 2005. [dostęp 26 March 2011].

- ↑ Ready for a Bush hug?. The Economist, 6 July 2006. [dostęp 19 March 2011].

- ↑ U.S.-German Economic Relations Factsheet. U.S. Embassy in Berlin, May 2006. [dostęp 26 March 2011].

- ↑ The 15 countries with the highest military expenditure in 2011 (table). [dostęp 2013-08-11]. (ang.).

- ↑ [The 15 countries with the highest military expenditure in 2011 (table) Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Artikel 65a,87,115b]. [dostęp 2013-08-11]. (niem.).

- ↑ Die Stärke der Streitkräfte. 23 marca 2012. [dostęp 2013-08-11]. (niem.).

- ↑ Ausblick: Die Bundeswehr der Zukunft. [dostęp 2013-08-11]. (niem.).

- ↑ Einsatzzahlen – Die Stärke der deutschen Einsatzkontingente. [dostęp 2013-08-11]. (niem.).

- ↑ Kate Connolly: Germany to abolish compulsory military service. [dostęp 2013-08-11]. (ang.).

- ↑ Floyd Norris: A Shift in the Export Powerhouses. [w:] The New York Times [on-line]. 20 February 2010. [dostęp 27 March 2011].

- ↑ CPI 2009 table. Transparency International. [dostęp 15 May 2012].

- ↑ The Innovation Imperative in Manufacturing: How the United States Can Restore Its Edge. Boston Consulting Group, March 2009. [dostęp 19 March 2011].

- ↑ Gross domestic product (2009). [w:] The World Bank: World Development Indicators database [on-line]. World Bank, 27 September 2010. [dostęp 1 January 2011].

,Field listing – GDP (official exchange rate). - ↑ Gross domestic product (2009). [w:] The World Bank: World Development Indicators database [on-line]. World Bank, 27 September 2010. [dostęp 5 October 2010].

, - ↑ Financial Crisis: EU budget: who pays what and how it is spent. Telegraph. [dostęp 2012-11-04].

- ↑ The Labour Market in May 2012: Positive Underlying Trend Weakens.

- ↑ Press office of the Deutsche Bundesbank: Deutsche Bundesbank – Statistics. Bundesbank.de. [dostęp 4 June 2012].

- ↑ Edmund L. Andrews: Germans Say Goodbye to the Mark, a Symbol of Strength and Unity. The New York Times, 1 January 2002. [dostęp 18 March 2011].

- ↑ Błąd w składni szablonu {{Cytuj stronę}}. Brak podanego adresu cytowanej strony (parametr url=|).

- ↑ Berg, S.; Winter, S.; Wassermann, A: The Price of a Failed Reunification. Spiegel Online, 5 September 2005. [dostęp 28 November 2006].

- ↑ Nicholas Kulish: In East Germany, a Decline as Stark as a Wall. [w:] The New York Times [on-line]. 19 June 2009. [dostęp 27 March 2011].

- ↑ Germany agrees on 50-billion-euro stimulus plan. [w:] France 24 [on-line]. 6 January 2009. [dostęp 27 March 2011].

- ↑ The 100 Top Brands 2010. Interbrand. [dostęp 27 March 2011].

- ↑ Gavin, Mike: Germany Has 1,000 Market-Leading Companies, Manager-Magazin Says. Businessweek, 23 September 2010. [dostęp 27 March 2011].

- ↑ Global 500: Countries – Germany. [w:] Forbes [on-line]. 26 July 2010. [dostęp 27 March 2011].

- ↑ Autobahn-Temporegelung. June 2010. [dostęp 19 March 2011]. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.).

- ↑ Geschäftsbericht 2006. Deutsche Bahn. [dostęp 27 March 2011]. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (9 August 2007)]. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.).

- ↑ Airports in Germany. Air Broker Center International. [dostęp 16 April 2011].

- ↑ Overview/Data: Germany. U.S. Energy Information Administration, 30 June 2010. [dostęp 19 April 2011].

- ↑ Energy imports, net (% of energy use). The World Bank Group. [dostęp 18 April 2011].

- ↑ Reuters Berlin: * Environment * Renewable energy Germany targets switch to 100% renewables for its electricity by 2050. The Guardian, 7 July 2010. [dostęp 18 April 2011].

- ↑ Primärenergieverbrauch nach Energieträgern. Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Technologie, December 2010. [dostęp 18 April 2011]. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.).

- ↑ Germany split over green energy. [w:] BBC News [on-line]. 25 February 2005. [dostęp 27 March 2011].

- ↑ Deutschland erfüllte 2008 seine Klimaschutzverpflichtung nach dem Kyoto-Protokoll. 1 February 2010. [dostęp 19 March 2011]. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.).

- ↑ Germany greenest country in the world. The Times of India, 21 June 2008. [dostęp 26 March 2011].

- ↑ Record High 2010 Global Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Fossil-Fuel Combustion and Cement Manufacture Posted on CDIAC Site. Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center. [dostęp 15 May 2012].

- ↑ Federal Report on Research and Innovation 2010. Federal Ministry of Education and Research, June 2010. [dostęp 15 May 2012].

- ↑ Nobel Prize. Nobelprize.org. [dostęp 27 March 2011].

- ↑ Swedish academy awards. ScienceNews. [dostęp 1 October 2010].

- ↑ National Science Nobel Prize shares 1901–2009 by citizenship at the time of the award and by country of birth. From Schmidhuber, J.: Evolution of National Nobel Prize Shares in the 20th century. 2010. [dostęp 27 March 2011].

- ↑ J.M. Roberts: The New Penguin History of the World. Allen Lane, 2002, s. 1014. ISBN 978-0-7139-9611-1.

- ↑ The First Nobel Prize. Deutsche Welle, 8 September 2010. [dostęp 27 March 2011].

- ↑ Otto Hahn. FamousScientists.org. [dostęp 15 December 2011].

- ↑ Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize. DFG. [dostęp 27 March 2011]. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (21 June 2008)].

- ↑ Luigi Bianchi: The Great Electromechanical Computers. York University. [dostęp 17 April 2011].

- ↑ The Zeppelin. U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. [dostęp 27 March 2011].

- ↑ Historical figures in telecommunications. International Telecommunication Union, 14 January 2004. [dostęp 27 March 2011].

- ↑ Roland Berger Strategy Consultants: Green Growth, Green Profit – How Green Transformation Boosts Business Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-28543-9.

- ↑ Key Figures on Europe. Belgium: European Union, 2011, s. 37. DOI: 10.2785/623. ISBN 978-92-79-18441-3.

- ↑ Country Comparison :: Population. CIA. [dostęp 26 June 2011].

- ↑ Demographic Transition Model. Barcelona Field Studies Centre, 27 September 2009. [dostęp 28 March 2011].

- ↑ Im Jahr 2060 wird jeder Siebente 80 Jahre oder älter sein. 18 November 2009. [dostęp 6 April 2012]. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.).

. Details on the methodology, detailed tables etc. are provided at Bevölkerungsentwicklung in Deutschland bis 2060. Statistisches Bundesamt, 18 November 2009. [dostęp 15 February 2011]. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (29 December 2010)]. (Błąd! Nieznany kod języka: German. Sprawdź listę kodów.). - ↑ Birth rate on the rise in Germany (The Local).